Drunkard's Special by Coley Jones [Anthology Revisited - Song 4]

TL;DR -- Song from the 1700's about a man who comes home drunk multiple times, and his wife who takes advantage of the situation. Hilarity ensues. Meanwhile, Coley Jones proves a hard man to pin down.

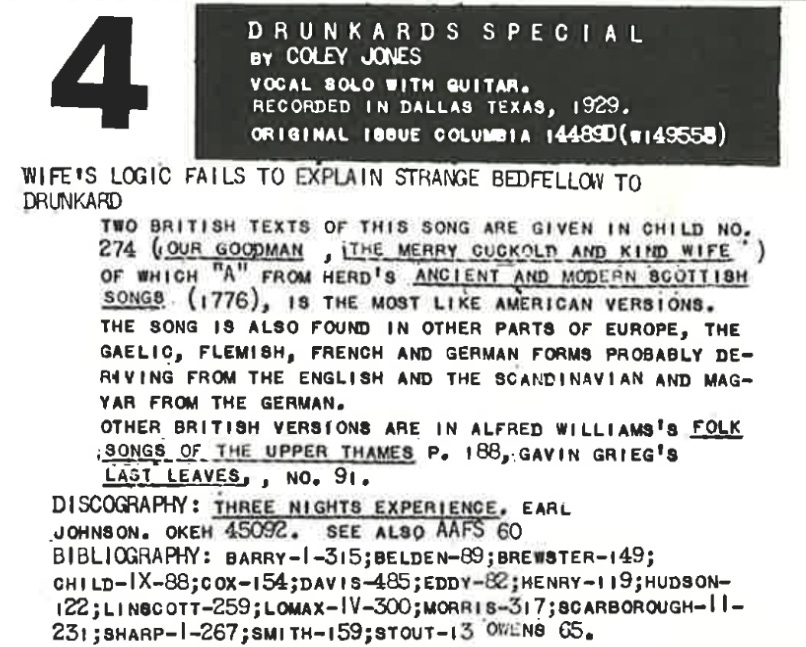

Welcome to the fourth installment of our journey through Harry Smith’s legendary 1952 compilation, The Anthology of American Folk Music. This time, we’re examining Coley Jones’ 1929 recording of "Drunkard's Special", an amusing Child ballad featuring a series of exchanges between drunken husband (who suspects his wife is up to something) and his wife (who absolutely is up to something).

So far in this series, we’ve covered the first three Child ballads that appear on Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music; “Henry Lee” (Child 68), “Fatal Flower Garden” (Child 155), and “The House Carpenter” (Child 243). Our trip up the Child ballad number line continues today with “Drunkard’s Special”, a song with roots in Child ballad number 274.

Before exploring this amusing tale, let’s start with Harry Smith’s headline…

WIFE’S LOGIC FAILS TO EXPLAIN STRANGE BEDFELLOW TO DRUNKARD.

This headline beautifully unpacks the entire song in a few words, hinting at the humorous nature of the song without explicitly calling it a comedic number.

The lyrics consist of a series of exchanges between a drunken man and his wife over the course of three evenings. Each night, the drunk comes home saying he’s seen something out of the ordinary. Although his notions are accurate and his eyes do not betray him, his wife uses his inebriation against him explaining away each sight as something entirely different. Each time, the poor old sot is baffled and unable to reconcile what he’s seen with the explanation she has provided, but ultimately goes along with his wife’s explanation just the same. Meanwhile, the wife has been visited by her lover on (at least) three occasions and almost gotten caught by her husband.

It’s quite the hoot. Check it out for yourself…

Lyrics

First night when I went home

Drunk as I could be,

There's another mule in the stable

Where my mule oughta be.Come here, honey.

Explain yourself to me.

How come another mule in the stable

Where my mule oughta be."O crazy, O silly

Can't you plainly see?

That's nothing but a milk cow

Where your mule oughta be."I've traveled this world over

Million times or more.

Saddle on a milk cow's back

I've never seen before.Second night when I got home

Drunk as I could be,

There's another coat on the coat rack

Where my coat oughta be.Come here, honey.

Explain this thing to me.

How come another coat on the coat rack

where my coat oughta be?"O crazy, O silly,

Can't you plainly see?

Nothing but a bed quilt

Where your coat oughta be."I've traveled this world over

Million times or more.

Pockets in a bed quilt

I've never seen before.

Third night when I went home

Drunk as I could be,

There's another head on the pillow

Where my head oughta be.Come here, honey… C'mere.

Explain this thing to me.

How come another head on the pillow

Where my head oughta be?"O crazy, O silly,

Can't you plainly see?

That's nothing but a cabbage head

That your grandma sent to me."I've traveled this world over,

Million times or more.

Hair on a cabbage head

I've never seen before.

The Song

“Drunkard’s Special” is an American variant of Child ballad 274, an English ballad originally titled “Our Goodman” that has spawned hundreds of variants, including “The Merry Cuckold and Kind Wife”, “Seven Nights Drunk”, “Three Nights’ Experience”, and “Old Witchet”, and plenty of others.

Coley Jones’ recording of the song only covers three nights, but the Child ballad follows the drunkard and his wife over the course of six evenings.

In instances where we have a performer like Coley Jones who was known to have a large repertoire, and a song with more known verses, I wonder how many verses Jones might have performed were he not constrained by the limitations of the recording equipment at the time. We’ll never know, but I ponder such notions just the same.

Smith notes that a Scottish variant of the song was printed in the 1776 collection Ancient and Modern Scottish Songs, Heroic Ballads, Etc. by David Herd, George Patton, and Sidney Gilpin, and while this seems to be the first printing of the song, it is suspected that the song originated in England in the 1750’s as “The Merry Cuckold and Kind Wife”, but this is unconfirmed. The lack of earlier confirmed printing could make one wonder if the “Scottish variant” might be the original, and Child 274A, the variant. Regardless of the song’s nation of origin, Child 274A (the full text of which is below) and the 1776 Scottish version, referenced by Smith, differ only in the spellings of some words, and a few minor alterations in phrasing (one of which I discuss in some detail below) that do nothing to change the overall content of the song.

Before we get to the text of “Our Goodman”, as collected by Child, I’ll break down the story as told in the original version of the ballad.

In verses 1-4, the husband comes home to see an unexpected horse in the stable. His wife explains this is a sow. The husband expresses surprise at the notion of a saddle on a sow.

In verses 5-8, the drunkard sees a pair of boots that aren’t his. His wife explains that these are water-stoups, and the husband is surprised to see silver spurs on water-stoups. (The term “water-stoup” was new to me, so I consulted Merriam-Webster. The word “stoup” can refer to one of two things. It can be a water vessel (similar to a flagon), or it can be a basin containing holy water. The second definition is the most common usage of the phrase, but context in the song suggests that the first definition is the intended meaning here.)

In verses 9-12, our man sees a sword, which his wife explains is “porridge-spurtle”. The husband replies that has never seen a porridge-spurtle with a silver handle. (A spurtle is a kitchen utensil designed to stir porridge or similar foods which require frequent stirring. The spurtle has a narrow end to ensure that the consistency of the food remains smooth and doesn’t clump up like it would if stirred by a spoon.)

Verses 13-16 find our man puzzled over an unexpected powdered wig in his house. His wife reassures him that this is merely a “clocken-hen” (a hen sitting on her eggs.), but the husband protests that he has never seen a powdered clocken-hen.

In verses 17-20, the drunkard is dismayed over the discovery of a muckle coat (an overcoat), which his wife explains is a blanket. The drunkard is baffled by the presence of buttons on a blanket.

In the final four verses, the drunkard grapples with the presence of a “study man” in his home. The wife tells him that this is no “study man”, but rather a milking-maid. The surprised husband exclaims that he has never seen a bearded milking maid, and the ballad concludes.

(I found no resource to explain the meaning of “study man” in this context. On the surface, it may mean a studious, educated man. However, the aforementioned Scottish variant uses the phrase “sturdy man”. The glossary from the source text defines “Sturdy” as “giddy-headed”, and as “strong” when referencing an object.

Now, dear reader, I leave it up to you. Was the man studious? Was he giddy-headed? Was he strong?

In the end, one’s interpretation of the “study” / “sturdy” man matters little. Even though the drunkard has discovered this fellow in his home, his wife seems to have successfully passed him off as a milkmaid.)

With that lengthy summary out of the way, here’s the full text of Child 274A, as promised.

274A: Our Goodman

274A.1

HAME came our goodman,

And hame came he,

And then he saw a saddle-horse,

Where nae horse should be.

274A.2

‘What’s this now, goodwife?

What’s this I see?

How came this horse here,

Without the leave o me?’

‘A horse?’ quo she.

‘Ay, a horse,’ quo he.

274A.3

‘Shame fa your cuckold face,

Ill mat ye see!

’Tis naething but a broad sow,

My minnie sent to me.’

‘A broad sow?’ quo he.

‘Ay, a sow,’ quo shee.

274A.4

‘Far hae I ridden,

And farrer hae I gane,

But a sadle on a sow’s back

I never saw nane.’

274A.5

Hame came our goodman,

And hame came he;

He spy’d a pair of jack-boots,

Where nae boots should be.

274A.6

‘What’s this now, goodwife?

What’s this I see?

How came these boots here,

Without the leave o me?’

‘Boots?’ quo she.

‘Ay, boots,’ quo he.

274A.7

‘Shame fa your cuckold face,

And ill mat ye see!

It’s but a pair of water-stoups,

My minnie sent to me.’

‘Water-stoups?’ quo he.

‘Ay, water-stoups,’ quo she.

274A.8

‘Far hae I ridden,

And farer hae I gane,

But siller spurs on water-stoups

I saw never nane.’

274A.9

Hame came our goodman

And hame came he,

And he saw a sword,

Whare a sword should na be.

274A.10

What’s this now, goodwife?

What’s this I see?

How came this sword here,

Without the leave o me?’

‘A sword?’ quo she.

‘Ay, a sword,’ quo he.

274A.11

‘Shame fa your cuckold face,

Ill mat ye see!

It’s but a porridge-spurtle,

My minnie sent to me.’

‘A spurtle?’ quo he.

‘Ay, a spurtle,’ quo she.

274A.12

‘Far hae I ridden,

And farer hae I gane,

But siller-handed spurtles

I saw never nane.’

274A.13

Hame came our goodman,

And hame came he;

There he spy’d a powderd wig,

Where nae wig shoud be.

274A.14

‘What’s this now, goodwife?

What’s this I see?

How came this wig here,

Without the leave o me?’

‘A wig?’ quo she.

‘Ay, a wig,’ quo he.

274A.15

‘Shame fa your cuckold face,

And ill mat you see!

’Tis naething but a clocken-hen,

My minnie sent to me.’

‘Clocken hen?’ quo he.

‘Ay, clocken hen,’ quo she.

274A.16

‘Far hae I ridden,

And farer hae I gane,

But powder on a clocken-hen

I saw never nane.’

274A.17

Hame came our goodman,

And hame came he,

And there he saw a muckle coat,

Where nae coat shoud be.

274A.18

‘What’s this now, goodwife?

What’s this I see?

How came this coat here,

Without the leave o me?’

‘A coat?’ quo she.

‘Ay, a coat,’ quo he.

274A.19

‘Shame fa your cuckold face,

Ill mat ye see!

It’s but a pair o blankets,

‘My minnie sent to me.’

‘Blankets?’ quo he.

‘Ay, blankets,’ quo she.

274A.20

‘Far hae I ridden,

And farer hae I gane,

But buttons upon blankets

I saw never nane.’

274A.21

‘Ben went our goodman,

And ben went he,

And there he spy’d a study man,

Where nae man shoud be.

274A.22

‘What’s this now, goodwife?

What’s this I see?

How came this man here,

Without the leave o me?’

‘A man?’ quo she.

‘Ay, a man,’ quo he.

274A.23

‘Poor blind body,

And blinder mat ye be!

It’s a new milking-maid,

My mither sent to me.’

‘A maid?’ quo he.

‘Ay, a maid,’ quo she.

274A.24

‘Far hae I ridden,

And farer hae I gane,

But lang-bearded maidens

I saw never nane.

https://sacred-texts.com/neu/eng/child/ch274.htm

The Performance

Recorded in Dallas, Texas on December 9, 1929 for Columbia Records, “Drunkard’s Special” features Coley Jones on guitar and vocals. The performance is a spirited, mid-tempo number in which Jones’ vocal delivery demonstrates that he was well-versed in the art of performing comedic numbers. When performing songs with punch lines, the vocal phrasing and comedic timing are the keys to making the jokes work, stumble on either, and the joke might not hit as expected. Coley Jones nails each punch line. As if it wasn’t obvious from the recording, Jones wasn’t new to performing comedy. He was a veteran of minstrel shows, so he knew how to tell a joke.

Jones’ guitar playing serves the song nicely. He holds the rhythm when delivering verses and uses a fun recurring phrase to punctuate each verse after the punch line. It’s a cute lick that gives a little room for audience to laugh before returning to the top for the next verse of the song.

The Performer

While we know that he could deliver a punchline, we don’t know too much more about Coley Jones. It’s known that he was an African-American man born in an unknown location somewhere around the year 1880. In Jones’ younger years, he played mandolin or guitar (depending on the song, I suppose) with his father (guitarist, Coley Jones, Sr.), and another guitar player whose name is lost to the ages. The trio is said to have performed throughout Texas in various settings and with various other performers. We do know that by 1903, Jones took up residence in Dallas, where he is believed to have remained through at least the 1920’s, if not the rest of his life. Jones also worked as a minstrel show performer and had a deep repertoire of material.

The bulk of the information we have about Coley Jones begins in 1927 and ends in 1929. During these years, Jones was the bandleader and vocalist for the Dallas String Band with whom he also played mandolin (and possibly guitar). The group toured throughout East Texas during this time, eventually becoming known as the Coley Jones String Band.

During the same period, Jones also performed alongside jazz drummer Hubert Cowans in the group the Satisfied Five, Cowans’ first professional gig. Some of the group‘s performances from the Baker Hotel in Dallas were broadcast live over WFAA radio.

The Illustrated Coley Jones Discography shows that from 1927-1929, Jones appeared on 22 recordings made in Dallas, TX and released by Columbia Records. Interestingly, Jones’ known recording sessions all took place in the early part of December. The dates were December 3-7, 1927, December 8-9, 1928, and December 4-6, 1929..

On December 3, 1927, Coley Jones recorded four songs on which he sang and played guitar, but none of these recordings were ever released. On December 4, 1927, Coley played guitar and sang on his first recording that would be released “Army Mule In No Man's Land”. The next day, he recorded the B-side “Travelling Man” [sic]. On December 6, 1927, Coley sang and played mandolin with the Dallas String Band on “Dallas Rag” and “Sweet Mama Blues”. On December 7, Jones and his guitar returned to the studio and recorded a version of “Frankie and Albert” that went unreleased.

In December 1928, the Dallas String Band returned to the studio to record four more tracks on which Jones played mandolin and sang. Their December 8 recording session produced “So Tired” and “Hokum Blues”, while “Chasin’ Rainbows” and “I Used to Call Her Baby”, were recorded the following day. These recordings were released with the performers listed as “Dallas String Band with Coley Jones”

In December 1929, Coley Jones returned to the Dallas studios of Columbia Records for three days that would be his final (and most productive) sessions. On December 4, 1929 he played guitar on six sides with pianist Texas Bill Day, two of which included Billiken Johnson on kazoo and vocal effects. (Links to these recordings can be found at the Illustrated Coley Jones Discography.)

On December 5, Jones played guitar and sang on two duets with vocalist Bobbie Cadillac, (“I Can’t Stand That” b/w “He Throws that Thing”), on which they were accompanied by a pianist who is thought to have been Alex Moore.

On December 6, 1929, Jones’ final day in the studio, he recorded his last two solo sides (“Drunkard’s Special” (above) b/w “The Elder's He's My Man”), and played mandolin and did some vocals on the final two Dallas String Band recordings (“Shine” b/w “Sugar Blues”). On the same day, he also played guitar and sang on two more vocal duets with Bobbie Cadillac (“Listen Everybody” b/w “Easin’ In”), once again joined by what is assumed to be the same pianist as the previous day.

This is where the details about Jones’ life end.

Like all the performers who appear on the Anthology, Jones is most certainly deceased, but no information about the year or location of his death has surfaced.

Speculation

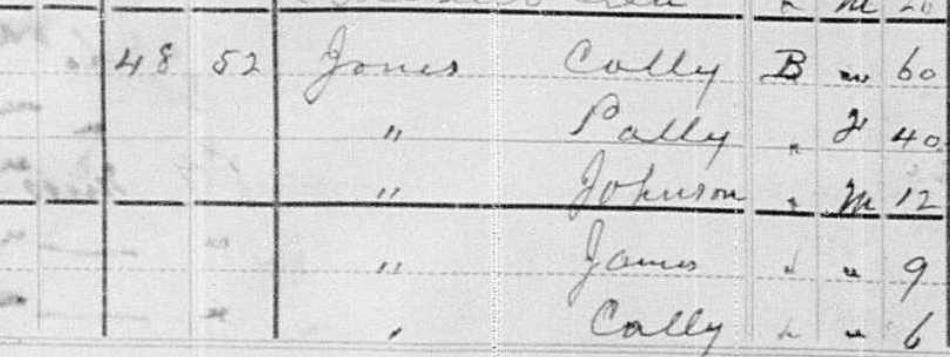

CAVEAT: What follows is exactly what the heading states… speculation. I do not claim to have uncovered any verifiable details about the performer Coley Jones apart from those I shared above. Having said that, I have uncovered some information that may be of interest.

I was unable to locate any verifiable information about Coley Jones via genealogy searches. The only plausible match I found was an 1880 U.S. Census entry from Galveston, Texas for a Black man named “Colly Jones”, who was born in Africa around 1820 and who had a wife and several children, one of whom was also named Colly Jones and was 6 years old at the time of the Census. This is the only record I have located for a non-white individual who lived in that area, during that era, and whose name might have been Coley Jones.

So we’ve got one assumption and three facts that we can use to consider this information. The running assumption is that Coley Jones was born around 1880. Since this is an assumption, 1873 or 1874 are plausible years for Jones’ birth. The three facts are that (1) Coley Jones had the same name as his father, (2) that he lived in Dallas, and (3) that Galveston is about 300 miles from Dallas.

So, is it plausible that this 6 year old “Colly Jones” from Galveston whose name appears in the 1880 U.S. Census could have grown up to be an itinerant musician who eventually settled in Dallas and recorded “Drunkard Special”?

NOTE: My research into the Anthology’s more obscure performers is ongoing. If new information comes to light, I will update this article to reflect the change. If you are aware of any additional biographical information about Coley Jones, kindly reach out.

Connections

We’ve come to the part in the article where I look for connections between this song and the ones that preceded it in an effort to demonstrate how meticulous Harry Smith was about the sequencing of this collection.

The first connection is that like the three songs before it, “Drunkard’s Special” is based on a Child ballad. As with the other Child ballads in the Anthology, the song’s Child catalog number is higher than that Child catalog number of the song that precedes it.

The previous song, "The House Carpenter," tells the tale of a woman who betrays her husband and child, abandoning them for an old flame who’s come to reclaim her love. Once she and her lover are at sea, she regrets her decision and soon the boat sinks. "Drunkard's Special" is also about marital issues, specifically betrayal by an unfaithful wife. Betrayal, and more specifically, the betrayal of a male character by a woman has been a consistent thread that runs through each of the first four songs of the Anthology.

“Drunkard’s Special” introduces humor to the Anthology, and is the first song in which no one dies. Perhaps Harry felt a bit of comic relief was needed after the horrors of the previous songs.

Other Interpretations

Discography

In the original liner notes, Smith provided a couple of examples of variants. The one mentioned by name is “Three Nights Experience” by Earl Johnson.

The second entry in Smith’s discography is a reference to AAFS 60, which is a version of “Our Goodman” performed by Orrin Rice in Harrogate, Tennessee in 1943 and recorded by Artus Moser. The song appears on volume twelve of Folk Music of the United States which bears the subtitle Anglo-American Folk Songs and Ballads from the Archive of American Folk Song Edited by Duncan B.M. Emrich.

Two years after this recording was made, Pfc Orrin Rice of the 325th Glider Infantry Regiment of the 82nd Airborne division of the US Army lost his life in the invasion of Normandy on June 11, 1945.

Interpretations from the other side of the pond

As we explore other versions of the song, we’ll start in the British Isles then head west across the Atlantic, kinda like the song did.

Steeleye Span takes the three night bender a little farther here with their 1971 recording of “Four Nights Drunk”.

The Dubliners transformed the song into “Seven Drunken Nights”, which was released in 1967, peaking at Number 7 on the UK Singles Chart.

CAVEAT/SPOILER: The title is a bit misleading.

Our Goodman gets the blues (and then some)

A few months before Coley Jones recorded “Drunkard’s Special”, another Texas artist, Blind Lemon Jefferson, recorded “Cat Man Blues” which isn’t a variant of “Our Goodman” in the most literal of senses. I think of it as sort of like a spin-off.

Blind Boy Fuller’s 1936 recording of “Cat Man Blues” is the same take on the song as the one Blind Lemon Jefferson gave us. But being a native of North Carolina, I have to share Blind Boy Fuller whenever the opportunity arises.

In 1958, Sonny Boy Williamson II hit “Our Goodman” with a different kind of blues, and called it “Wake Up Baby”.

Finally, 1971 found “Our Goodman” in the streets of New Orleans with Professor Longhair’s “Cabbagehead”.

Conclusion

Alas, it’s time to wrap up the tale of our good man, the oblivious drunk. The song represents a couple of firsts in our journey through the Anthology. Not only is it the first comedy piece to appear on the Anthology, this is the first song in the collection that was performed by an African-American.

We went back to Scotland and England to uncover the origins of the song (and decipher some archaic terminology), then returned to the States in search of something (anything) more about Coley Jones, only to come up with a tiny hint of something that might not be anything.

Next time around, we’ll continue the explorations of Child ballads and themes of marital discord when Bill and Belle Reed sing “The Old Lady and the Devil”, an amusing song about a woman who was so mean that even the devil himself didn’t want anything to do with her.

As always, thanks for riding along on this adventure. I couldn’t have done it without the work of many other people over the years. The resources I consulted when writing this analysis are below. If you’re looking more information, they’re a great place to start.

If you have any corrections, suggestions, or additional information I didn’t cover, please share it in the comments. If you appreciate this series, please subscribe and share it with folks you think might enjoy it.

Sources

274. Our Goodman - The Child Ballads

https://sacred-texts.com/neu/eng/child/ch274.htm

Ancient and Modern Scottish Songs, Heroic Ballads, Etc. by David Herd, George Patton, and Sidney Gilpin. (1776)

https://archive.org/details/ancientandmoder01unkngoog/page/n183/mode/2up?view=theater

Stoup (definition)

https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/stoup

Spurtle (Wikipedia)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spurtle

Coley Jones

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coley_Jones

Illustrated Coley Jones / Dallas String Band discography

https://www.wirz.de/music/jonescol.htm

Person entry for possible match of Coley Jones as “Colly Jones” in 1880 U.S. Census

(NOTE: Familysearch.org is a free site, but users must create an account to view content).

https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9YBK-DVV?view=index&action=view&cc=1417683&lang=en&personArk=%2Fark%3A%2F61903%2F1%3A1%3AMFN8-QZG

"Texas, United States records," images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9YBK-DVV?view=index : Apr 10, 2025), image 251 of 744; United States. National Archives and Records Administration. Image Group Number: 005162538

Folk Music of the United States - Anglo-American Folk Songs and Ballads from the Archive of American Folk Song Edited by Duncan B.M. Emrich. - AAFS L12 - AAFS 60.

https://archive.org/details/lp_anglo-american-songs-and-ballads_various-charles-ingenthron-doney-hammontre/disc1/02.08.+Our+Goodman.mp3

4 “The Drunkard’s Special” by Coley Jones | My Old Weird America

https://oldweirdamerica.wordpress.com/2008/12/04/4-the-drunkards-special-by-coley-jones/

"Drunkard's Special" - Coley Jones | Where Dead Voices Gather - Life at 78rpm

https://theanthologyofamericanfolkmusic.blogspot.com/2009/11/set-one-ballads-disc-one-track-four.html

From Where I Stand: The Black Experience in Country Music | Disc 1: The Stringband Era } Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum

https://www.countrymusichalloffame.org/from-where-i-stand/disc-1-the-stringband-era

Coley Jones | Handbook of Texas } Texas State Historical Association

https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/jones-coley