Gonna Die with My Hammer in My Hand by Williamson Brothers and Curry [Anthology Revisited - Song 18]

TL;DR -- Quixotic Luddite defeats steam drill, loses life. John Henry and John Hardy were different people. Jubilant recording believed (by some) to include fourth performer.

Welcome to the eighteenth installment of Anthology Revisited, a song-by-song journey through the Anthology of American Folk Music, a collection of commercial recordings originally released between 1926 and 1932 that was assembled by Harry Smith and released on Folkways Records in 1952 and reissued by Smithsonian Folkways in 1997.

In this edition, we examine one of the Great American Folk Songs, “Gonna Die with my Hammer in my Hand”, which tells the story of John Henry, as performed by Williamson Brothers and Curry on April 26, 1927 in the studios of OKeh records in St. Louis, Missouri.

We are in the heart of the third side of Volume One - Ballads, and in this edition, we’ve got a West Virginia trio delivering an exuberant performance of a tremendous song about John Henry, the steel-driving man whose legend inspired many words to be written and many songs to be sung.

For the past several weeks, we’ve had a couple of big themes running. The primary theme was the “Timeline” theme which has taken us on a six-song trip through the 1800’s beginning in 1801 with “Peg and Awl”, moving forward with each song until we got to 1894 in the previous installment with “John Hardy was a Desperate Little Man”, which was also the fifth consecutive song to have a person’s name in the title.

This time, in an interesting twist in sequencing, Harry Smith has broken away from both the “Timeline” and “Titular Character” themes for a moment to bring this John Henry song into the mix. While it technically breaks the theme, I tend to think of this song’s placement as more of a sidebar in the conversation instead of a break from the theme. I’ll explain what I mean in the Connections section.

I’ve tried to keep these introductory remarks brief because, as has been the case over the past several weeks, there’s a whole lot of stuff to discuss, especially in “The Song”, because this is a John Henry ballad, and there’s a lot to talk about. So let’s check out Harry Smith’s headline and get on our way.

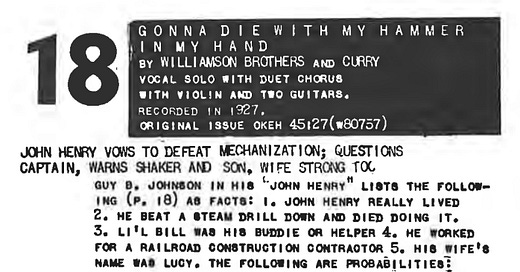

JOHN HENRY VOWS TO DEFEAT MECHANIZATION; QUESTIONS CAPTAIN, WARNS SHAKER AND SON, WIFE STRONG TOO

Another pithy headline from Harry that gives us a bare bones breakdown of just what we’re working with. The opening is a powerful summary “vows to defeat mechanization”. That’s bold. Not wrong, just bold. The “Wife strong too” closing is fantastic. Because the headline opens with such a potent phrase, these final words seem somehow more meaningful, as if to suggest that perhaps Mrs. John Henry was also imbued with some otherworldly strength.

The Shaker

I don’t typically introduce material from the song before the video, but since Harry Smith’s headline used the term “shaker”, I thought a quick rundown of some steel-driving lingo might help you have a clearer mental picture of what’s going down in the song. Especially in lines like these.

John Henry told his shaker,

"Shaker, you better pray.

For if I miss this six foot steel,

Tomorrow be your burying day.”

John Henry was part of a crew digging a tunnel. As a steel driver, Henry hammered a drill into the rock to create a small hole into which explosive powder could be poured, then later detonated, to enlarge the tunnel. The shaker was the driver’s right hand man. His job was to hold the steel drill in place for the driver to hit with the hammer. Between blows of the hammer, the shaker would turn and shake the drill a bit, to remove any smaller rocks that had been broken up by the previous blow. With this in mind, the stanza above will probably make a whole lot more sense.

Alright, before I give away any more information out of order, let’s get down to business and give this song a listen. Recorded for OKeh records in St. Louis, Missouri on April 26, 1927, here are the Williamson Brothers and Curry, with “Gonna Die with My Hammer in My Hand”.

NOTE: To hear all the recordings referenced in this article, visit the Anthology Revisited playlist for this song on YouTube.

Lyrics

John Henry, he told his captain:

"A man ain't nothin' but a man.

Before I be beaten by this old steam drill,

I'm gonna die with my hammer in my hand.

Lord, lord! Die with my hammer in my hand."John Henry, he told his captain:

"Captain, how can it be?

The Big Bend Tunnel on the C&O Road

Is gonna be the death of me.

Lord, lord! Gonna be the death of me."John Henry had a little hammer.

Handle was made of bone.

Every he hit the drill on the head

Hammer reaches down and groans.

Lord, lord! Hammer reaches down and groans.John Henry, he told his shaker:

"Shaker, you better pray.

For if I miss this six foot steel,

Tomorrow be your burying day.

Lord, lord! Tomorrow be your burying day."John Henry had but one only son.

Sat in the palm of your hand.

The very last words John Henry said:

"Son, don't be a steel driving man.

Lord, lord! Son don't be a steel driving man."John Henry had a little woman.

Her name was Sally Ann.

John Henry got sick and he could not work.

Sally drove her steel like a man.

Lord, lord! Sally drove her steel like a man.

The Song

The tale of John Henry is one of the most sung, discussed, and dissected tales in the canon of American folklore. For over a century and a half since his death, John Henry has remained an iconic American figure.

The real John Henry was a Black steel driver who worked in the railroad construction business in the late 1800’s. An especially strong and skilled worker, Henry was part of a team digging a tunnel for the railroad company when a new piece of machinery, the steam drill, was brought to the job site. The steam drill could purportedly do the work of multiple men, and Henry, the strongest among the steel driving men, felt a need to prove himself superior to the technology. A competition was arranged between John Henry and the steam drill, and while Henry proved victorious over the steam drill, he paid for the victory with his life.

Tales of Henry’s act spread, his legend grew, and somewhere along the way, two completely different types of John Henry songs sprang up. There’s the ballad, like this one, and then there’s the ‘hammer song’, which is more contemplative and expresses a feeling more than it tells a story.

Fortunately, examples of both types of John Henry songs appear on the Anthology of American Folk Music. The 80th track of this collection, “Spike Driver Blues” by Mississippi John Hurt, which appears on the final side of Volume Three - Songs is a ‘hammer song’. The article on that song will be a companion to this one, continuing the examination of John Henry.

In this text, I’ll examine the ballad and treat the location suggested in this recording as fact. In the piece on “Spike Driver Blues”, I’ll share an entirely different (yet equally possible) version of the story, so please don’t get attached to this as the absolute, verifiable, undeniable truth about John Henry.

As Smith mentioned in the liner notes, Gus Johnson’s 1928 book John Henry: Tracking Down a Negro Legend, explores the Henry myth in detail. (The full text is available at the Internet Archive). As Smith mentioned in the liner notes, Johnson identified certain facts and probabilities.

Facts:

John Henry really lived

He beat a steam drill down and died doing it

Li’l bill was his buddie or helper

He worked for a railroad construction contractor

His wife’s name was Lucy

Probabilities:

He died in the early 1870’s

He was a Virginian

He worked on the C & O or a branch of that system

His captain was Tommy Walters; probably the assistant foreman

The Williamson Brothers and Curry’s version of the John Henry ballad begins with one of the more common opening verses. It introduces Henry via his claim to his captain that he’d die with his hammer in his hand before being beaten by the steam drill. Although the competition between Henry and the steam drill is at the core of the folk tale, it isn’t mentioned after the first verse of this recording. Verse two shares the location of events (Big Bend Tunnel on the C&O (rail)road), and Henry’s concern that he may not leave the tunnel alive. Verse three is one of those spooky folk song metaphors that describes the relationship between Henry and his stylized hammer, showing the tool as an extension of the man. Verse four is a snapshot from the tunnel, John Henry was racing against the steam drill, warning his shaker to pray that he didn’t miss his mark, (a valid concern considering where the shaker stood in relation to the business end of John Henry’s hammer). The last two verses tell us about John Henry’s family. He has a very small son and, whom Henry discourages from entering the steel-driving profession in his final words. Then, once John Henry “got sick and could not work”, his wife, Sally took up his hammer, and “drove her steel like a man”. Interestingly, John Henry is never declared dead in this song.

Big Bend Tunnel

The version of events presented in this song take place during the construction of the Big Bend Tunnel on the Chesapeake and Ohio (C & O) Railroad between 1870 and 1872 near what is now Talcott, West Virginia (a town named for Capt. Talcott, a civil engineer who was in charge of the Big Bend Tunnel’s construction).

IMAGE SOURCE: https://www.nps.gov/neri/learn/historyculture/images/web_Big_Bend_sign_square_1.jpg

During this period, steam power was used in an array of industrial applications, and the railroad company wanted to see if the steam drill might be a more efficient way of drilling through a mountain. A contest was staged that pitted John Henry and his shaker, L’il Bill, against the new steam powered drill.

The steam drill put up a good fight, but without a shaker to clear debris, the machine repeatedly needed attention. In the end, John Henry and L’il Bill beat out the steam drill, but Henry lost his life.

Guy Johnson devotes an entire chapter of his 1928 book to the Big Bend tunnel theory, and after sharing the findings of multiple interviews with persons who claimed to have known John Henry when he was at Big Bend, Johnson summarizes the Big Bend inquiry with the following:

Now, we might ask, where are we? Was there a John Henry? Did he beat a steam drill at Big Bend Tunnel? Are we any nearer an answer to these questions than we were when we began?

I submit that the foregoing data may be made to prove almost anything in regard to John Henry. For the sake of argument, take the position that there was no steam drill at Big Bend Tunnel and, consequently, no contest.

One might argue as follows. There are only three out of twelve persons included in the above interviews who claim to have seen John Henry. Only one of these three claims to have seen the contest. Nearly all of the others believe that the contest did not occur. One or two of these believe that it might have occurred, but they are basing their judgment on hearsay plus a possibility that the thing could have happened.

https://archive.org/details/johnhenrytrackin0000guyb/page/42/mode/2up?view=theater

Johnson concludes the chapter by stating:

Thus one can make out a case either for or against the truth of the John Henry tradition on the basis of evidence available at Big Bend Tunnel. Which case is the more logical I cannot say, for there are other things to be considered before a conclusion can be reached with any safety.

https://archive.org/details/johnhenrytrackin0000guyb/page/44/mode/2up?view=theater

To this, I’ll add that one thing you’ll notice here is that unlike previous articles where a real person has been discussed, there are no newspaper reports or genealogical data about John Henry.

No known newspapers reported the contest between John Henry and the steam drill, although Johnson indicated that such contests were relatively commonplace. Because we don’t know where Henry lived at any given time, attempting to locate genealogical or burial information for the man would be a fool’s errand. This lack of such concrete evidence would make it easy to dismiss the John Henry story as merely a myth. But drilling contests were a real thing, and there remains enough circumstantial evidence to suggest the story is true. Whether or not it happened on the C & O Railroad at the Big Bend Tunnel in West Virginia is up for debate, and as Johnson pointed out in his book, there are reasons why the events could have happened in West Virginia, but there are also abundant reasons to consider other options. A little over a year from now, when we get to “Spike Driver Blues” by Mississippi John Hurt, (song 80 on the Anthology), we’ll discuss the other possibilities.

The John Hardy Disconnect

“John Henry is related to John Hardy, as balladry goes, but wears brighter bandannas.”

- Carl Sandburg

It’s feels a bit odd to discuss a controversy that was settled nearly 100 years ago, but it is part of this song’s story and, in this author’s opinion, the main reason “Gonna Die with My Hammer in My Hand” was sequenced immediately after “John Hardy was a Desperate Little Man” on the Anthology. That the lyrics of both songs follow an identical pattern suggests that there could actually be some legitimate connection between the songs, and this connection led some folks to believe the songs were about the same person.

In his book, Johnson cites John Harrington Cox’s essay on John Hardy, a source referenced in the previous edition of this series.

From various persons in West Virginia, Cox obtained data concerning John Hardy. Ex-Governor McCorkle contributed a history of John Hardy. His statement in full, as quoted by Cox, is as follows:

He [John Hardy] was a steel-driver, and was famous in the beginning of the building of the C. & O. Railroad. He was also a steel-driver in the beginning of the extension of the N. & W. Railroad. It was about 1872 that he was in this section. This was before the day of steam-drills; and the drillwork was done by two powerful men, who were special steeldrillers. They struck the steel from each side; and as they struck the steel, they sang a song which they improvised as they worked. John Hardy was the most famous steel-driller ever in Southern West Virginia. He was a magnificent specimen of the genus Homo, was reported to be six feet two, and weighed two hundred and twenty-five or thirty pounds, was straight as an arrow, and was one of the most handsome men in the country, and, as one informant told me, was as “black as a kittle in hell.” (Johnson, p.55).

The following is from another source that Cox had interviewed.

John Hardy, a Negro, worked for Langhorn, a railroad contractor from Richmond, Va., at the time of the building of the C. & O. Road. Langhorn had a contract for work on the east side of the Big Bend Tunnel, which is in the adjoining county of Summers, to the east of Fayette County; and some other contractor had the work on the west side of the tunnel. This was the time when the steam-driller was first used. Langhorn did not have one, but the contractor on the other side of the tunnel did; and Langhorn made a wager with him that Hardy could, by hand, drill a hole in less time than the steamdrill could. In the contest that followed, Hardy won, but dropped dead on the spot. (Johnson, p.58)

Johnson goes on to evaluate Cox’s sources, then introduces information that had come to light after Cox’s 1918 piece was published. Johnson goes through a thorough analysis, that I’ll leave you to read for yourself. Johnson concludes that John Henry ballads began to emerge in the 1880s and became known throughout the land. The John Hardy ballads didn’t come into being until the 1890s and were much more regional in popularity. As we discussed in the previous article, some claimed that John Hardy wrote part of all of the song that bears his name. If John Henry songs were floating around in the 1880’s then there’s no way John Henry and John Hardy could’ve been the same man. Johnson goes on to postulate that:

The author of John Hardy, whether he was Hardy himself or someone else, must have been familiar with the structure of John Henry, for he cast his product in exactly the same mold. (Johnson p. 64)

And this is what your author believes to have happened. I think that the verses and tune of John Henry had been around a while. After the John Hardy song (with the exact same textual structure) came along, performers began to swap verses between the songs, whether intentionally or not. Other performers learned these mashed up versions and presumably thought they were singing the “real” John Henry (or John Hardy) song. Over time, the two songs and characters became more and more entangled with one another. Fortunately, the work of John Harrington Cox and Guy Johnson helped untangle the mess, and we can definitively state that John Henry and John Hardy were two distinct different individuals, each with his own tale.

The Performers (Part One)

NOTE: For reasons that will become clear in a moment, this article deviates slightly from the standard format. Typically, the section on “The Performance” immediately follows “The Song”, and is then followed by “The Performers”. Here, a discussion of the personnel is needed before The Performance can be effectively examined. To accommodate this need, I’ve split The Performers section into two parts. This part examines the brief recording career of Williamson Brothers and Curry, while Part Two provides general biographical information about the performers.

In the late 1920’s, Ervin Williamson, his younger brother, Arnold Williamson, and their friend Arnold Curry were coal miners in Logan County, West Virginia. The trio made music together for fun, and occasionally for pay at coalfields, local dances and the like. They ran in the same musical circles as Dick Justice (who recorded “Henry Lee”, the first song of the Anthology) and were friends with Frank Hutchison, whose January 1927 recording of “Stackalee” will be featured in the next edition of this series.

In 1926 and early 1927, Hutchison had recording sessions for OKeh in New York City. After returning from his second OKeh session in January 1927, Hutchison helped the Williamsons and Curry secure a recording session for OKeh in St. Louis, Missouri on April 26, 1927, and accompanied the trio on the trip to cut 8 sides of his own. (More about Frank Hutchison in the next installment of this series.)

The Williamson Brothers and Curry’s one-day recording career yielded six sides, all of which featured Ervin Williamson on guitar, Arnold Williamson on fiddle, and Arnold Curry on banjo-ukulele. All six sides were released, and links to each of the songs are below. They are quite a fun group, and the whole catalog takes less than half an hour to experience, so if you’ve got the time, here are the links. (These tracks are also collected in the Anthology Revisited 18 - Gonna Die with My Hammer in My Hand YouTube playlist.)

Lonesome Road Blues - written by Henry Whitter, commonly known as “Goin’ Down the Road Feelin’ Bad”.

Throughout the recordings, Arnold Curry is flailing the banjo-uke most of the time, but occasionally does some picking. The guitar, played by Ervin Williamson, is the rhythmic core, and also seems to be the source of the short, descending bass runs that appear throughout the recordings.

While researching this recording, I came across the Williamson Brothers and Curry page on West Virginia University’s Folk Music of the Southern West Virginia Coalfields website. The page contains the image above and indicates that the fourth man was probably named Albert Kirk and that he was known to play with the trio from time to time. The caption for the image suggested that Kirk could be heard on the Williamson Brothers and Curry’s 1927 recordings, but the article contained no further mention of Kirk’s presence in the studio.

I say all of this because the statement regarding Albert Kirk’s presence in the St. Louis sessions was new information to me. The claim is not supported by the Discography of American Historical Recordings entries for the Williamson Brothers or Arnold Curry, and Kirk’s name is not in Tony Russell’s Country Music Records: a discography 1921-1942. The DAHR cites Russell as a source for the information provided there, and I checked Russell’s book to see if there were any further clues. Here’s what it said.

Russell’s discography (pictured above) makes no mention of Kirk’s presence, and leaves the vocalists unidentified for all six Williamson Brothers and Curry sides. Russell indicates that there are two vocalists on “Gonna Die with My Hammer in My Hand”, and three singers on “Lonesome Road Blues” and “Warfield” but offers no clues to the identity of the lead vocalist on any track.

The photo of the performers shows Arnold Williamson holding the fiddle in a manner that suggests that he could have been a vocalist. Because Arnold Williamson looks to have been a singing fiddler, this means that the three vocalists on “Lonesome Road Blues” and “Warfield” are accounted for in the studio logs.

Since we can’t use the number of vocalists to confirm or refute Kirk’s presence, it all boils down to whether or not two guitars can be heard in their recordings. The liner notes in Smith’s original release and those in the 1997 reissue indicate the song has two guitars and a fiddle. I’m not so sure about that. I hear a fiddle and one guitar, and I also hear Arnold Curry’s banjo-ukulele. I can also completely understand how Curry’s instrument could easily be mistaken for a second guitar if one doesn’t know to listen for a third instrument that is neither a guitar nor fiddle. But, do I hear a second guitar on top of those three instruments? Well….

I’m hard of hearing, which means I’m not the best person to make this call. I invite you to listen to these recordings on your own and make your own determinations. In the final section of this article, I’ll tell you what I think I hear on “Gonna Die with My Hammer in My Hand”, but I will defer to those with better hearing to determine the actual instrumentation of this track.

The Performance

By this point, it should be crystal clear why I felt the need to introduce the performers prior to discussing The Performance.

We know that Ervin Williamson (guitar), Arnold Williamson (fiddle), and Arnold Curry (banjo-ukulele) appear on this recording. We don’t (and can’t) know who sang on this track, and we know that Albert Kirk may be lurking back there on a second guitar.

But before we get too far into the whole Kirk thing, I want to introduce the banjo-ukulele. The instrument is exactly what the name suggests. It’s a ukulele, but instead of the instrument’s body being that of a miniaturized guitar, it’s a mini banjo. Like a standard ukulele, the banjo-uke only has four strings, and sounds similar to a five-string banjo, although there are some differences that may be heard in the recording with a close listen.

This particular recording presents a disjointed version of the John Henry tale. The storyline is jagged, but these jagged edges really don’t matter here. These are West Virginia coal miners singing about John Henry, a man who also knew a thing or two about being inside of West Virginia mountain. They didn’t need to be precise. They didn’t need to deliver the full narrative. They just needed to be themselves, and sing a song to honor their fellow underground laborer.

And they delivered. This may not be an astounding display of instrumental or vocal skill, but the exuberance in this recording is infectious. The subject is a man who is literally working himself to death, and these guys sound like they couldn’t be happier about it.

But they’re not jubilant because John Henry is dead. The Williamson Brothers and Curry were miners. They knew what it was like to work inside of the earth day in and day out. This bond they shared with John Henry adds a layer of authenticity to this performance that is hard to match. These men who’ve spent hours underground recognize Henry’s grit and determination and celebrate it with an almost giddy awe.

This was the sixth and final track recorded in their first (and only) visit to a recording studio, and I suspect the giddy awe could also be partly due to the whole band being loaded on adrenaline, which all came flooding out in this final performance. They gave it all they had, and what they had was mighty fine.

On Albert Kirk and the second guitar

I’ve listened to this recording repeatedly at varying speeds via the player embedded on the DAHR page for the song. I can hear Curry flailing the banjo-uke, but it’s not easy to separate from the guitar, especially with the vocals on top.

To better determine the personnel on this recording, I took a .WAV file of the recording and used StudioOne to slow down the track to 75% its original speed. Then, I removed the vocals from the track. I created a second track into which I restored the vocals, but at a much lower volume. I then created the video below, and added some notes about the recording and what I’m hearing. I hope you’ll give it a listen and decide for yourself just how many musicians are on this track. I am hard of hearing, and my lone ear might fail to hear sounds that are clear to your ears.

NOTE: My opinion on who plays on this recording is in the Conclusion of this article.

The Performers (Part Two)

Having discussed their recording career in The Performers (Part One) above, this section is devoted to providing biographical details about the Williamson Brothers and Curry.

The Williamson Brothers

The eldest Williamson child, William Ervin Williamson, was born on November 2, 1900 in Wayne County, WV, and his brother Arnold was born on January 1, 1904 in the same county. The first US Census records on which the brothers appear is from 1910. At that time, the Williamson family lived on a farm in the Lincoln District of Wayne County, West Virginia. 35 year old Charlie Williamson, their father, appears on the Census as the operator of the farm, and 9 year old Ervin is listed as a laborer. Six year old Arnold and four year old Moses and their mother Malinda “Ninnie” Williamson (25) round out the household.

Ten years later, when the 1920 US Census was conducted, the family lived in the Logan magisterial district of Logan County, WV where Charlie (listed on the Census as “Chas”) worked as a coal miner, as did his sons Erving and Arnold (ages 19 and 16 respectively). The 14 year old Moses, who didn’t have a job in 1910, remained jobless in 1920.

Ervin Williamson

On August 15, 1924, Ervin got married for the first time. His bride was seventeen year old Brookie May Queen. Based on the information available, it doesn’t seem as if Ervin and Brookie’s marriage worked out too well.

After the April 1927 recording session, the next record on which Ervin Williamson appears comes from April 17, 1928, and contains tragic information. On this date, Cora Lou Williamson, Ervin Williamson’s daughter, passed away two days after her birth. Cora Lou Williamson was not the child of Ervin’s wife, Brookie May, but rather another woman named Polly Sammons.

The 1930 US Census found Ervin, Arnold,and Moses still living with their parents in the Logan magisterial district of Logan County. This time, all three Williamson boys were working in the coal mine, but there were two other folks in the house.

Polly, with whom Ervin had a child in 1928, was living in the home and is listed as Charlie Williamson’s “Daughter in Law”, but she hadn’t taken the Williamson name. Instead, her last name “Sammons” is butchered on the Census as “Salmonis”. There’s another “Salmonis” in the house as well, a young Rudolph, who is less than a year old. The Census has Rudolph listed as Charlie’s stepson, but that doesn’t make a whole lot of sense. I suspect Rudolph may have been another child of Ervin and Polly, but cannot confirm this because we have no further records of Rudolph.

Ervin and Polly had two children who definitely survived infancy; their son, Floyd (born in or around 1932), and daughter Helen, (born in 1935). According to the 1940 U.S. Census, the family of four had moved out of Williamsons’ parents’ home and in to their own place before April 1, 1935, but still remained in the Logan magisterial district of Logan County. (This information comes from the 1940 U.S. Census, which visited the Williamsons on April 20, 1940, and included a question regarding the residence of each occupant on April 1, 1935. All four were listed as living in the “Same place”.)

On February 6, 1940, Ervin’s wife, Brookie May Williamson died of a sudden heart attack. Eleven days later, on February 17, 1940, Ervin Williamson and Polly Sammons were married in Belfry, Kentucky, just across the West Virginia/Kentucky border. We knew that Polly and Ervin had been together since at least 1928, but they didn’t get married until 1940, less than two weeks after Ervin’s (assumedly estranged) wife died. Tragically, Ervin and Polly were married just a little over a year. On May 21, 1941, Polly Williamson died from a pulmonary embolism after acute appendicitis.

On July 22, 1948, the 46 year old, twice widowered Ervin Williamson married for the third time. His new bride was 23 year old Ethel Mae Muncey. At the time of their wedding, Ervin was no longer in the mine and was working as a store clerk. In 1950, Ervin and Ethel still lived in the Logan magisterial district, with Ervin’s son Floyd (18), and his two sons by Ethel, Billy (9) and Homer (2),

Ervin Williamson died on March 29, 1972 at Saint Mary’s Hospital in Huntington, West Virginia of lung cancer, which had metastasized and spread. Prior to his death, he was a truck driver for a packing company. Williamson’s remains were buried in Forest Lawn Cemetery in Peck’s Hill, Logan County, West Virginia.

Arnold Williamson

All that is known of Arnold Williamson’s life up until 1930 was included in Ervin’s tale above. Apart from this, there’s little else that we know about Arnold.

On July 1, 1939, Arnold and Ervin’s father, Charlie Williamson died of stomach cancer. The following year, when the U.S. Census came through, Arnold was living with his mother and working as a coal miner. In October 1940, Arnold’s World War II Draft Registration Card was completed. He was listed as 5’11½” tall, with a weight of 160 pounds, brown hair and brown eyes. He had no job at the time.

In 1948, Arnold married Emma Audrey Zornes, and they remained together for the next 50 years, until Arnold’s death in 1998. According to Hillbilly-Music.com, Arnold became an expert in refrigeration and worked for the Mountain State Packing Company for many years, perhaps even into the 1980's.

I found no other records about Arnold Williamson’s activities in life, only that he died on November 3, 1998 and was buried in Highland Memorial Gardens in Chapmanville, Logan County, West Virginia.

Arnold Curry

As with the Williamson brothers, the first US Census records to include Arnold Curry come from 1910, when he was the second youngest of seven children born to farmer Andrew Curry and his wife Phoebe in Logan County, West Virginia. In 1920, the census showed the 13 year old Arnold living with his parents and five of his siblings in Logan County. His father was working as a coal miner, and in the 1920 census, two of Curry’s older sisters May and Roxie, (who were, respectively, 13 and 16 years old in 1910) had already moved out, and the Curry’s had another daughter, Ona in or around 1913.

1927 was a big year for Arnold Curry. On June 12, 1927, about six weeks after his lone recording session in St. Louis, Missouri, Arnold Curry, our 21 year old miner and musician from Verdunville, WV married 17 year old Evelyn Hannah of Stone Branch WV were married in Stone Branch. In 1930, Arnold and Evelyn were living with Arnold’s parents, as were Arnold’s sisters Toka (21) and Nickie (28), Nickie’s three children and another child listed as a nephew. By this time, Andy Curry had returned to farming, but Arnold was still in the mine.

On January 21, 1935, Arnold Curry was killed in an automobile accident. He was returning home in dense fog when he drove over an embankment into a creek, and he drowned in about 20 inches of water. He was buried in Baisden Cemetery in Logan County, WV.

Connections

Regular readers of this series know that I’m particularly fond of the sequencing of the Anthology, and like to examine the many ways in which Smith weaves various themes together in the set. At the top, I mentioned that this song is a bit of a sidebar in our Timeline theme of songs about real (or fictionalized) events arranged in the order in which the events took place, so let me explain what I mean.

The Timeline, thus far, has consisted of the following songs

12 - Peg And Awl (1801-1804)

13 – Ommie Wise (1807)

14 – My Name Is John Johanna (1870’s)

15 – Bandit Cole Younger (1870’s; key event - 1876)

16 – Charles Giteau (1881-1882)

17 – John Hardy Was A Desperate Little Man (1893-1894)

This song obviously ends our streak of Titular Characters, and since John Henry died sometime in the early 1870’s (in this telling), it appears our timeline has been thrown out of whack. The timeline resumes in the next song, “Stackalee”, which takes place on Christmas 1895 (a year after the final events of “John Hardy was a Desperate Little Man”).

Because of this, I view the placement of “Gonna Die with My Hammer in My Hand” as more of a sidebar from the Timeline theme that branches off from the discussion on the conflation of John Henry and John Hardy, and simultaneously introduces the first of two consecutive acts to emerge from the West Virginia coalfields. Furthermore, the source that ultimately clarified the John Hardy / John Henry mix-up is the text Harry Smith referenced in his notes for this song. No coincidence.

Let me put it to you like this. If the Anthology was a radio show, Harry Smith would have the opportunity to pause before playing this track to say something to the effect of “While we’re on this whole John Hardy/John Henry thing, let’s step outside of the timeline for a moment and check out this take on John Henry by these West Virginia coal miners. If it sounds kinda familiar, the verse structure is identical to our previous track.” But Harry Smith didn’t have the chance to do that on the Anthology, because it was a set of albums, not a radio show. So, I’m here to ask you to consider the idea that this song is a sidebar to the previous song and doesn’t mark the end of the Timeline.

“Gonna Die with My Hammer in My Hand” is our first song about life on the job since “My Name is John Johanna”, and it contains a fascinating parallel to another song about life on the job, “Peg and Awl”.

The shoemakers in “Peg and Awl” reacted to new technology in the workplace with wonder and awe, walking away from the scene muttering “Some shoemaker” and shaking their heads in amazement. Like the shoemakers, John Henry had an encounter with new technology in the workplace, but his reaction couldn’t have been more different. John Henry didn’t walk away in awe. He looked progress square in the eye, said “I don’t think so.” went into battle with the technology, emerged victorious, only to die shortly afterwards.

The last connection is one that wasn’t intentional. In “John Hardy…” the autoharp made its first appearance on the Anthology (though Smith claimed the autoharp was present in Track 9, ‘Old Shoes and Leggins’, it wasn’t on that recording), and the banjo-ukulele makes its first appearance here (something which Smith doesn’t acknowledge at all). So Harry Smith inadvertently provided us with yet another example of how string bands were assembled.

Other Interpretations

This section examines other recordings of this song and variants of the John Henry ballad, performed by other artists. Whenever Smith’s notes include a Discography, this section is divided into two segments, “Discography”, which examines Smith’s selections, and “Further Interpretations”, wherein the selections are of this author’s choosing. Please note that these are not strict recreations of the Williamson Brothers and Curry’s recording by any stretch. Instead, they offer up a sample of the various flavors in which the John Henry ballad appears. We’ve not even touched on the ‘hammer songs’, which we’ll explore in the 80th installment of this series.

Discography

Birmingham Jug Band - Bill Wilson - This is cool, and definitely worth a spin. The song uses the structure and fundamental lyrics from John Henry, but instead of being a tale about a steel driving man, it’s about a wagon driving man. Meanwhile John Hardy entanglements appear, as Bill Wilson’s wife wears a red dress.

John Carson - John Henry Blues - This version was recorded in 1924 and is among the earliest known recordings of the John Henry ballad.

Dave Macon - Death of John Henry - We’ve got a couple of Uncle Dave Macon songs coming up on Volume Three - Songs, and I’m always happy when he appears in the Discography. He had a distinctive sound, and always seemed to be having a blast. This 1925 recording is no exception.

Henry Thomas - John Henry - speaking of performers who appear on the Anthology and always sound like they’re having a good time, we’ve also got a version of John Henry from Henry Thomas. We’ve got two Henry Thomas songs coming up later as well, and those quills (which produce the whistling sounds in the recording) make him an unmistakable performer. This performance is from July 1, 1927 in Chicago, Illinois.

Arthur Bell - John Henry - (Appears as AAFS 15 in Smith’s notes) - This field recording of Arthur Bell singing and using the hammer as an instrument was made by made by Alan and Ruby Lomax at Cummins State Farm, Camp #5, near Verner, Arkansas on May 20. 1939. Although Bell uses a hammer as a rhythmic instrument, this is still a version of the John Henry ballad and not a ‘hammer song’.

J.E. Mainer - John Henry was a Little Boy - Mainer has appeared in the Bibliography before, and this recording ultimately appeared on Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music Volume Four.

Further Interpretations

Mississippi Fred McDowell - John Henry - this is a wild, electric performance that flies way outside of the lines of standard John Henry ballads, but Mississippi Fred McDowell always did things in his own way, which is perfectly fine by me. This take features some stock lines from John Henry ballads, but it’s also got John Henry’s wife dressed in red, as well as lines that will reappear in Furry Lewis’ “Kassie Jones”, in a few weeks.

Woody Guthrie, Brownie McGhee, and Sonny Terry - John Henry - How cool is this? That’s a rhetorical question, y’know. We’ve got three legends performing a song about another legend.

Foggy Mountain Boys - John Henry - Frank “HyLo” Brown takes the lead vocals here, and if you give it a listen, it’ll soon become clear why he was given the peculiar nickname of HyLo.

Doc and Merle Watson - John Henry - Is this the best John Henry recording ever? Probably. Doc and Merle are backed by some serious players, and this really is one of the finest sounding recordings of John Henry that I’ve ever come across.

Billy Strings - John Henry - Last one… it’s got Billy Strings and an acoustic guitar, and it cooks, but of course it does. Billy Strings is the real deal, and artists like him give me reason to believe this music is gonna be around for at least a couple more generations.

Conclusion

Thanks for hanging around for all of this. We’ve covered an incredible amount of territory but we stayed within the borders of West Virginia most of the time, hanging out with West Virginia coal miners Ervin and Arnold Williamson, and their pal Arnold Curry and talking about John Henry, the Quixotian Luddite who lost his life after battling the seemingly lost cause of mechanization while (allegedly) constructing the Big Bend Tunnel in West Virginia.

We’ve looked into the John Henry legend, cleared up any remaining confusion over John Henry and John Hardy, and spent time getting to know the three men whom we know for sure appeared on this recording, and postulating whether or not a second guitarist was in the recording. On this topic, I promised to share my opinion in the conclusion, and here we are.

Do I think Albert Kirk appeared as a second guitarist on the recording of “Gonna Die with My Hammer in My Hand”? I do not. I agree with the data presented by Tony Russell and the DAHR. Ervin Williamson played guitar, Arnold Williamson played fiddle, and Arnold Curry played banjo-ukulele. One of those men sang lead vocals and another joined in on the refrain.

However, I will concede that I could be wrong. I’ve not analyzed the five remaining Williamson Brothers and Curry recordings in search of a second guitar to see if Kirk may have played on some but not all of the sides made on April 26, 1927. Being mostly deaf makes this a difficult proposition, and I must choose my battles. Besides, I’ve still got 66 songs to write about. So, I’ll wave the white flag, and leave the analysis of the remaining Williamson Brothers and Curry recordings, and the search for the presence of a second guitar to those better equipped to listen for such things.

Speaking of listening, if you’d like to check out all of the recordings included or mentioned in this installment, the Anthology Revisited 18 - Gonna Die with My Hammer in My Hand playlist on YouTube has it all, except for the slowed down version of “Gonna Die with My Hammer in My Hand” embedded in the “Performance” section of this piece.

In the next installment of Anthology Revisited, we’ve got “Stackalee” by Frank Hutchison, a song that takes place on Christmas Day, 1895. Just because it takes place on Christmas, don’t start thinking we’re shifting gears and moving into the holiday songs theme because that ain’t happening. The events may occur on Christmas, but the song isn’t about the deeds of some joyous soul caught up in the spirit of the season.

As always, I must close with a reminder that while these pieces contain many words, these articles are built upon the work of others and none of this stuff (except the parts that are obviously opinions) comes out of my brain. To dig deeper into the John Henry story, the Williamson Brothers and Curry, or any of the other topics discussed in this article, the sources I used when assembling this piece are below, and should serve as good springboards for your own explorations.

AUTHOR’S NOTES: This Substack is a one-man operation. Anthology Revisited is a labor of love. I am an independent writer, hoping to create a work of substance and contribute something of value to the ongoing conversation. Your likes, restacks, and comments are tremendously appreciated. If you want to support my work (or contact me beyond the comments section), there are a few options.

You can subscribe to this Substack. You’ll receive these articles in your inbox, and all you have to do is click the “Subscribe now” button below and enter your email address in the box that appears.

You can pass this article along to someone else who might like it via the “Share” button. I really hope you’ll do this. I know there’s an audience for this, I just don’t know where to find them. If you know a person or group of folks who might find this interesting, kindly pass this article along, and together, we’ll find the niche into which this fits.

This article is part of a series called Anthology Revisited, which is part of my publication, Rodney Writes about Music. To share this whole shebang with others, click the “Share Rodney writes about music” button below. (If you share the publication, the link will point to the landing page, where the introductory article for Anthology Revisited is prominently featured.)

This project is a labor of love and my attempt to put myself on the map as a music researcher and writer, and I don’t have paid subscriptions enabled at the moment. But this is a whole lot of work, and if you’d like to chip in to the “help Rodney keep the lights on” fund, click the “Buy Me a Coffee” button.

If you’d like to offer any corrections, have any suggestions, or have any specific questions about Anthology Revisited, email me directly at rodney.hargis at outlook.com.

Sources

The Legend of John Henry: Talcott, WV - New River Gorge National Park & Preserve (U.S. National Park Service)

https://www.nps.gov/neri/planyourvisit/the-legend-of-john-henry-talcott-wv.htm

John Henry and the Coming of the Railroad - New River Gorge National Park & Preserve (U.S. National Park Service)

https://www.nps.gov/neri/learn/historyculture/john-henry-and-the-coming-of-the-railroad.htm

John Henry (folklore) - Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Henry_(folklore)

John Henry: Tracking Down a Negro Legend

Johnson, Guy B.

University of North Carolina Press, 1929

Chapel Hill, NC

https://archive.org/details/johnhenrytrackin0000guyb/page/n11/mode/2up

The American Songbag

Sandburg, Carl

John Henry p 25

Harcourt Brace and Company

New York City, NY, 1927

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/cb/Carl_Sandburg_-_The_American_Songbag.pdf

Journal of American Folk-Lore, Volume 32, No. 126

John Hardy

Cox, John Harrington

October-December 1919, pp.505-520.

https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/John_Hardy

Williamson Brothers - Discography of American Historical Recordings

https://adp.library.ucsb.edu/index.php/mastertalent/detail/101094/Williamson_Brothers

Arnold Curry - Discography of American Historical Recordings

https://adp.library.ucsb.edu/index.php/mastertalent/detail/310517/Curry_Arnold

Hillbilly-Music.com -Williamson Brothers and Curry

https://www.hillbilly-music.com/groups/story/index.php?id=17468

Photo - Williamson Brothers and Curry - Folk Music of the Southern West Virginia Coalfields

https://omekas.lib.wvu.edu/home/s/folkmusic/item/3049

Williamson Brothers and Curry - Folk Music of the Southern West Virginia Coalfields

https://omekas.lib.wvu.edu/home/s/folkmusic/page/the-williamson-brothers-and-curry

Country Music Records: A Discography 1921-1942

Russell, Tony;

Pinson, Bob; Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum

p. 960

Oxford University Press, 2008

New York, NY

https://archive.org/details/countrymusicreco00russ/page/960/mode/1up

Ervin Williamson | FamilySearch

https://www.familysearch.org/en/tree/person/about/KVLJ-4HT

William Ervin Williamson | FindAGrave

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/205093025/william_ervin-williamson

West Virginia Deaths 1804-1999 | Ervin Williamson

https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:NM43-62P

"West Virginia, Deaths, 1804-1999", FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:NM43-62P : Sat Aug 31 04:51:00 UTC 2024), Entry for William Ervin Williamson and Charlie Williamson, 29 Mar 1972.

https://archive.wvculture.org/vrr/va_view2.aspx?FilmNumber=2114527&ImageNumber=2144

Entry for Ervin Williamson and Ethel M Williamson, US Census, 1950.

https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:6F3Y-Y5SG

"United States, Census, 1950", FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:6F3Y-Y5SG : Mon Mar 17 19:07:27 UTC 2025), Entry for Ervin Williamson and Ethel M Williamson, 26 April 1950.

Kentucky, County Marriages, 1786-1965 | Ervin Williamson 22 Jul 1948

https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:Q2DX-J5TT

"Kentucky, County Marriages, 1786-1965", FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:Q2DX-J5TT : Sat Feb 24 07:58:00 UTC 2024), Entry for Ervin Williamson and Charley Williamson, 22 Jul 1948.

West Virginia Deaths 1804-1999 | Brookie May Williams

https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:NMQJ-DP8

"West Virginia, Deaths, 1804-1999", FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:NMQJ-DP8 : Sat Aug 31 03:09:02 UTC 2024), Entry for Mrs Brookie May Williams and Dave Queen, 06 Feb 1940.

https://archive.wvculture.org/vrr/va_view2.aspx?FilmNumber=1983476&ImageNumber=2138

West Virginia Marriages 1780-1970 | Irvin Williamson and Brookie Queen, 1924

https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:FR1Z-GZD

West Virginia, Marriages, 1780-1970, database, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:FR1Z-GZD : 29 November 2018), Irvin Williamson and Brookie Queen, 1924; citing Marriage, Logan, West Virginia, United States, county clerks, West Virginia; FHL microfilm .https://archive.wvculture.org/vrr/va_view2.aspx?FilmNumber=571283&ImageNumber=374

West Virginia Deaths, 1804-1999 | Polly Williamson 29 May 1941

https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:NMQH-F88

"West Virginia, Deaths, 1804-1999", FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:NMQH-F88 : Sat Aug 31 04:43:19 UTC 2024), Entry for Polly Williamson and Randolph Sammons, 29 May 1941.

https://archive.wvculture.org/vrr/va_view2.aspx?FilmNumber=1983560&ImageNumber=654

Kentucky, County Marriages, 1786-1965 | Ervin Williamson and Charlie Williamson, 17 Feb 1940.

https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:Q2DH-59JJ"Kentucky, County Marriages, 1786-1965", FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:Q2DH-59J6 : Sat Feb 24 02:13:09 UTC 2024), Entry for Ervin Williamson and Charlie Williamson, 17 Feb 1940.

Entry for Ervin Williamson and Polly Williamson, US Census, 1940.

https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:K7C5-T8K

"United States, Census, 1940", FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:K7C5-T8K : Sun Jan 19 15:58:28 UTC 2025), Entry for Ervin Williamson and Polly Williamson, 1940.

Entry for Cora Lou Williams and Ervin Williams, 17 Apr 1928

https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:F1YX-221

"West Virginia, Deaths, 1804-1999", FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:F1YX-22B : Sat Aug 31 04:25:19 UTC 2024), Entry for Cora Lou Williams and Ervin Williams, 17 Apr 1928.

Entry for Charlie H Williamson and Ninie Williamson, US Census, 1910

https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MPJW-G2C

"United States, Census, 1910", FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MPJW-G24 : Sun Mar 10 04:09:29 UTC 2024), Entry for Charlie H Williamson and Ninie Williamson, 1910.

Entry for Chas Williamson and Ninie Williamson, US Census, 1920

https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MN2X-PFG

"United States, Census, 1920", FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MN2X-PF2 : Wed Jan 22 16:14:08 UTC 2025), Entry for Chas Williamson and Ninnie Williamson, 1920.

Arnold Williamson | FamilySearch

https://www.familysearch.org/en/tree/person/details/LB8H-Y4R

Arnold James Williamson | FindAGrave

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/53573280/arnold-james-williamson

West Virginia Deaths 1804-1999 | Charlie Williams 1 Jul 1939

https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:NM3R-FJ2

"West Virginia, Deaths, 1804-1999", FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:NM3R-FJ2 : Sat Aug 31 04:38:47 UTC 2024), Entry for Charlie Williams and Mose Williams, 01 Jul 1939.

https://archive.wvculture.org/vrr/va_view2.aspx?FilmNumber=1983473&ImageNumber=243

United States, Census, 1940 | Melinda Williamson and Charlie Williamson

https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:K7C5-B43

"United States, Census, 1940", FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:K7C5-B4S : Sun Jan 19 09:08:10 UTC 2025), Entry for Melinda Williamson and Arnold Williamson, 1940

West Virginia, World War II Draft Registration Cards, 1940-1945 | Arnold James Williamson

https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:Q2CY-24ZH

"West Virginia, World War II Draft Registration Cards, 1940-1945", FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:Q2CY-24ZH : Tue Apr 29 19:45:12 UTC 2025), Entry for Arnold James Williamson and Ninnie Williamson, 16 Oct 1940.

Entry for Andrew R Curry and Phoebe A Curry, United States Census, 1910

https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MPNY-1W1

"United States, Census, 1910", FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MPNY-1WG : Sun Mar 10 03:14:42 UTC 2024), Entry for Andrew R Curry and Phoebe A Curry, 1910.

Entry for Andy Curry and Phoebe Curry, United States Census, 1920.

https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MN2F-Y2C

"United States, Census, 1920", FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MN2F-Y2Q : Tue Jan 07 16:23:24 UTC 2025), Entry for Andy Curry and Phoebe Curry, 1920.

Entry for Andy Curry and Phoebe Curry, United States Census, 1930.

https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:XMHW-W56

"United States, Census, 1930", FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:XMHW-W57 : Sat Mar 09 17:43:58 UTC 2024), Entry for Andy Curry and Phebe Curry, 1930.

Marriage Record, Arnold Curry and Evelyn Hannah

https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:FR1W-SHH

West Virginia, Marriages, 1780-1970, , FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:FR1W-SHH : 29 November 2018), Arnold Curry and Evelyn Hannah, 1927; citing Marriage, Logan, West Virginia, United States, county clerks, West Virginia; FHL microfilm .

https://archive.wvculture.org/vrr/va_view2.aspx?FilmNumber=571283&ImageNumber=306

Arnold Curry | FamilySearch

https://www.familysearch.org/en/tree/person/details/KWJH-SSF

Arnold Curry | FindAGrave

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/36097342/arnold-r-curry

I discovered this Substack just this morning, and I am overwhelmingly impressed by both the passion and the scholarship you put into it. Just finished reading (well, skimming, really) the article on John Henry. Fantastic job, Rodney! Once you complete all 84 songs from the Anthology, you will have produced a landmark piece of research on American folk music. Very well done, indeed!