John Hardy was a Desperate Little Man by the Carter Family [Anthology Revisited - Song 17]

TL;DR -- Hardy slays man in craps game, money partly to blame. Colorful dresses abound. Tale errantly conflated with that of John Henry. Surface scratched on Carter Family.

Welcome to the seventeenth installment of Anthology Revisited, the song-by-song journey through Harry Smith’s influential compilation, the Anthology of American Folk Music, released on Folkways Records in 1952 and reissued by Smithsonian Folkways in 1997.

This week, we’re taking our first look at the First Family of Country Music, the Carter Family, and their May 10, 1928 recording of “John Hardy was a Desperate Little Man”, another song about real people and real events in the late 19th century.

This is the sixth song in the Timeline section of Volume One - Ballads, and our fifth consecutive song to feature someone’s name in the title, and our second consecutive song about a desperate little man who winds up on the gallows.

John Hardy is a song about which much has been written, and while the Carter Family may not be a household name throughout the USA anymore, plenty has been written about them over the years. Throughout this series, I try to make each article a comprehensive resource for the song and artist. That won’t be the case today. There is plenty more to learn about both John Hardy and the Carter Family beyond this article.

The song has a tangled history. Some folklorists thought John Hardy and John Henry were the same person, (they’re not), and there was a bit of confusion about it all some hundred years ago. We’ll explore this confusion over the truth, and more in the section on The Song.

The performers need no introduction, but they’ll get one just the same. Simply put, the Carter Family played a tremendous role in defining the genre of country music. In previous installments of Anthology Revisited, the 1927 Bristol Sessions (aka the “Big Bang of Country Music”) have been mentioned, and in this edition, we’ll show where the Carter Family fit into the whole picture.

There’s quite a bit to cover, so let’s get to it and start our journey into this vague and compelling little number with a look at Harry Smith’s headline.

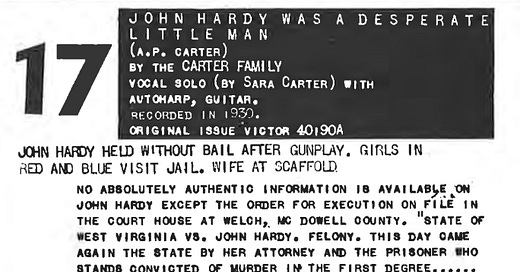

JOHN HARDY HELD WITHOUT BAIL AFTER GUNPLAY. GIRLS IN RED AND BLUE VISIT JAIL. WIFE AT SCAFFOLD.

This seemingly vague headline proves quite clear upon investigation. In the headline, Smith ignores all subtext and provides an abbreviated retelling of the song’s key events. The song’s lyrics tell a story, but go light on specifics. As Smith reports, Hardy is jailed without bail after killing a man, is refused bail, is visited by girls in red and blue, goes to the scaffold, where his wife is beside him, and is hanged by the neck until dead.. There are a couple of other things that happen, but overall, that’s the gist of it.

We’ll get into the details in a bit, but first, let’s give this song a listen. If you’ve never listened to the Carter Family, then you may be wondering what all the fuss is about. Well, you’re about to find out. This song is a great introduction to their work, and the whole thing starts off with Mother Maybelle Carter demonstrating her “Carter scratch” guitar technique. Check it out!

Lyrics

John Hardy, he was a desperate little man,

He carried two guns every day.

He shot a man on the West Virginia line,

And you ought see John Hardy getting away.John Hardy, he got to the Keystone Bridge,

He thought that he would be free.

And up stepped a man and took him by his arm,

Says, "Johnny, walk along with me."He sent for his poppy and his mommy, too,

To come and go his bail.

But money won't go a murdering case;

They locked John Hardy back in jail.John Hardy, he had a pretty little girl,

That dress that she wore was blue.

As she came skipping through the old jail hall,

Saying, "Poppy, I've been true to you."John Hardy, he had another little girl,

That dress that she wore was red.

She followed John Hardy to his hanging ground,

Saying, "Poppy, I would rather be dead.""I been to the East and I been to the West,

I been this wide world around.

I been to the river and I been baptized,

And now I'm on my hanging ground."John Hardy walked out on his scaffold high,

With his loving little wife by his side.

And the last words she heard poor John-O say,

"I'll meet you in that sweet bye-and-bye."

The Song

As Harry Smith’s notes indicate, this is, in fact, a true story, and the tale told by the song provides an accurate telling of the story, albeit one short on details. Here’s what the song tells us:

Hardy was a desperate gun-toting fella.

Hardy shot a man on the West Virginia line.

Hardy was captured at Keystone Bridge and jailed.

Hardy was charged with murder, and bail was denied.

Hardy had female visitors while in jail.

Hardy found religion and got baptized

Hardy hanged by neck until dead

Smith’s notes give a bit more information, sharing that Hardy was an employee of the Shawnee Coal Company and killed a man in a craps game for 25 cents. Hardy’s execution was ordered by the State of West Virginia at the conclusion of Hardy’s trial in McDowell County, WV, and Hardy was scheduled to be hanged on January 19, 1894.

Since Harry wrote these liner notes, more information has come to light, and I’ve tried to assemble more complete accounting of events, which I’ve split into two sections: the first provides a relatively straightforward recounting of the events based on newspaper articles, the second includes interviews with persons with direct knowledge of the events and leaves you to draw your own conclusions.

The Straightforward Telling of Events

The October 13, 1893 edition of the Wheeling Daily Register contained the following:

WELCH, W. VA, October 12. - At 8 o’clock this morning the jury in the case of the State against John Hardy, colored, for the murder of Thomas Drews, colored, at Eckman, this county, in January last, brought in a verdict of guilty of murder in the first degree. The trouble arose over a game of craps and was a cold blooded crime. Motion has been made for a new trial with but small hopes of success on account of the Criminal Court Judge’s indisposition. A recess has been taken until Monday.

On October 12, 1893, John Hardy, a Black employee of the Shawnee Coal Company in McDowell County, West Virginia, was found guilty of the January 1893 murder of Thomas Drews in Eckman, West Virginia. According to court records, Hardy shot and killed Drews in front of several witnesses after Drews had beaten Hardy in a craps game. While not part of the court record, several sources indicate that the killing was over twenty-five cents, as Harry Smith reported.

It was also revealed that Hardy had an accomplice, Webb Gudger, who was waiting in the wings with a Winchester just in case Hardy missed his target. Gudger was found guilty of voluntary manslaughter and sentenced to four years in the state penitentiary.

After killing Drews, Hardy made a run for it, but was captured on the back of an outbound train by Sheriff John Effler. According to Effler, he fought with Hardy for several minutes on the train, and they fell off the train together. Though Effler was injured in the fall, Hardy was quickly subdued by bystanders and arrested by Effler.

At his trial, Hardy was found guilty of murder, and sentenced to die. The sentence was carried out on January 19, 1894 before a crowd of about 3,000 people. Hardy found religion in jail, and was baptized a few hours before the hanging. Hardy allegedly gave a remorseful gallows speech, in which he warned of the dangers of liquor.

The January 19, 1894 edition of the Wheeling Daily Register reported the following:

John Hardy, for killing Thomas Drews, both colored, was hung at 2:09 p.m. today. Three thousand people witnessed his death. His neck was broken and he died in 17 ½ minutes. He exhibited great nerve, attributed his downfall to whiskey, and said he had made peace with God. His body was cut down at 2:39, placed in a coffin, and given to the proper parties for interment. He was baptized in the river this morning.

Ten drunken and disorderly persons among the spectators were promptly arrested and jailed. Good order was preserved. Hardy killed Drews near Eckman last spring in a disagreement over a game of craps.BOTH WERE ENAMORED of the same woman, and the latter proving the more favored lover, incurred Hardy’s envy, who seized the pretext of falling out in the game to work vengeance on Drews, who had shown himself equally expert in dice as in love, having won money from Hardy. Hardy drew his pistol, remarking he would kill him unless he refunded the money. Drews paid back part of the money, when Hardy shot, killing him. Hardy was found guilty at the October term.”

https://www.appalachianhistory.net/2019/01/john-hardy-attributed-his-downfall-to.html

This article about Hardy’s hanging gives us a clearer understanding as to why Hardy killed Drews, and that final paragraph tells us a lot. It certainly bolsters the claims made in the song, which says that Hardy was married, but was visited in jail by at least two women (one in red, one in blue). That Hardy killed Drews over the affections of a woman further solidifies the notion that Hardy was a ladies man, and offers a ready explanation for each of the lady visitors in the song, (one was his wife, and the other was his mistress).

The Twist

The above is such a straightforward recounting of events that I would love to leave it as it stands and say “Yup. That’s what went down”, and move on to the next section, but that’s not how it works.

Extracting truth from folk songs isn’t always a simple affair, and my research occasionally uncovers contradicting viewpoints that I must try and reconcile. Above, I have assembled a very tidy little story that could work to explain this song, but there are other claims about this song that should be shared. As with the previous song (“Charles Giteau”), there are claims that this song’s subject and author are the same person. I am convinced that Guiteau had no hand in writing the song that bears his name, but what about John Hardy? Did he write this song?

Personally, I doubt that the entire song was composed by Hardy, but I can’t help but wonder if there is something to the claims. I’ll share what I’ve uncovered and will let you draw your own conclusions.

The first source is Alan Lomax’s 1960 book Folk Songs of North America. In his text, Lomax references an Anglo-Scots ballad as a potential source. The ballad is ‘Little Matty Groves’, and the textual structure of the stanzas in both songs is quite similar, but please don’t take that to mean that John Hardy is a variant of Little Matty Groves. It is not. The songs merely share a similar lyrical structure.

Note: Any emphasis (bold or italics) in the text below was added by this author, and does not appear in the original sources.

141. JOHN HARDY

One of the most rousing American ballads and the best of mountain banjer' pieces' is the story about the Negro murderer, John Hardy. Because he worked in the tunnels of the West Virginia mountains in the same epoch as John Henry, the two songs have sometimes been combined by folk singers, and the two characters confused by ballad collectors. The fate of steel-driving John Hardy, however, took him on another path than John Henry's. He shot and killed another Negro in a crap game at Shawnee Coal Company's Camp, a place now called Eckman, West Virginia. His white captors protected him from a lynch mob that came to take him out of jail and hang him. When the lynch fever subsided, Hardy was tried during the July term of the McDowell County Criminal Court, found guilty and sentenced to be hanged. While awaiting execution in jail, he is said to have composed this ballad, which he later sang on the scaffold. He also confessed his sins to a minister, became very religious, and advised all young men, as he stood beneath the gallows, to shun liquor, gambling, and bad company. The order for his execution shows that he was hanged near the courthouse of McDowell County, January 19, 1894. His ballad appears to have been based upon certain formulae stanzas from the Anglo-Scots ballad stock.

Lyrics allegedly penned by Hardy

John Hardy was a brave little man,

He carried two guns ev'ry day,

Killed him a man in the West Virginia land,

Oughta seen poor Johnny gettin' away, Lord, Lord,

Oughta seen John Hardy gettin' away.John Hardy was standin' at the barroom door.

He didn't have a hand in the game,

Up stepped his woman and threw down fifty cents,

Says, 'Deal my man in the game, Lord, LordJohn Hardy lost that fifty cents,

It was all he had in the game,

He drew the forty-four that he carried by his side

Blowed out that poor Negro's brains, Lord, Lord ...John Hardy had ten miles to go,

And half of that he run,

He run till he come to the broad river bank,

He fell to his breast and he swum, Lord, Lord . . .He swum till he came to his mother's house,

' My boy, what have you done?'

' I've killed me a man in the West Virginia land,

And I know that I have to be hung, Lord, Lord . . .'He asked his mother for a fifty cent piece,

‘My son, I have no change.’

‘Then hand me down my old forty-four

And I'll blow out my agurvatin' brains, Lord, Lord ..:John Hardy was lyin' on the broad river bank,

As drunk as a man could be;

Up stepped the police and took him by the hand,

Sayin' ' Johnny, come and go with me, Lord, Lord..:John Hardy had a pretty little girl,

The dress she wore was blue.

She come skippin' through the old jail hall

Sayin' “Poppy, I'll be true to you, Lord, Lord.”John Hardy had another little girl,

The dress that she wore was red,

She came skippin' through the old jail hall sayin'

' Poppy, I'd rather be dead, Lord, Lord ..’They took John Hardy to the hangin' ground,

They hung him there to die.

The very last words that poor boy said,

' My forty gun never told a lie, Lord, Lord. • •

There are some noteworthy variations between these words from Lomax’s book, and those on the Carter Family’s recording. First, this ballad describes Hardy as brave, not desperate. The second and third verses give us a description of the moments leading up to the murder that the Carter Family don’t provide. Here, Hardy’s female companion gets Hardy into the craps game, and after his money is lost, Hardy takes someone’s life.

Verses four through seven take us with John Hardy as he flees the scene and provide a different perspective. Hardy takes the ten mile journey to his mother’s house, first running, then swimming. When he arrives, his mother has no money to give him, and Hardy asks for a gun with which to kill himself. The next thing we know, he’s drunk on the riverbank and approached by the police.

The last three verses are familiar. The women in red and blue come to visit his cell, and Hardy is hanged to end the song.

(It’s worth noting here that the Carters likely knew more verses to “John Hardy” than they recorded. When preparing for recording sessions, they carefully edited the ballads, removing verses as needed to ensure that their performance would last less than three minutes.)

The Twist - Supporting Evidence

In the opening of this piece, I mentioned how John Hardy and John Henry were thought by some to have been the same person. I’ve avoided this topic thus far to focus on the facts around John Hardy, but now I want to look at the confusion around Hardy and Henry, and discuss how it was cleared up, because it is from the clarifying source that we get some fascinating claims that lend credence to Lomax’s statements.

All the information below comes from the October-December 1919 edition of the Journal of American Folk-Lore (Vol. 32, No. 126), which contained an article by John Harrington Cox simply titled “John Hardy”. In the article, Cox explores the roots of both songs, examines the Hardy/Henry controversy and demonstrates very clearly that these are two separate individuals.

Cox includes court information gathered for him by a former student, along with interviews with locals who were around in the 1890’s and were thought to have had additional information about Hardy. What follows are excerpts from Cox’s article, with slight adjustments to improve readability, any statements made in the first person are coming from Cox, not from this author.

Mr. Ernest I. Kyle, a former student of West Virginia University, whose home is at Welch, [West Virginia] and whom I asked to look up the records of the trial and also to report such other data as he could secure, in a letter dated Sept. 14, 1917, writes as follows: —

"John Hardy (colored) killed another Negro over a crap game at Shawnee Camp. This place is. now known as Eckman, W.Va. (the name of the P.O.). The Shawnee Coal Company was and is located there. Hardy was tried and convicted in the July term of the McDowell County Criminal Court, and was hanged near the courthouse on Jan. 19, 1894. While in jail, he composed a song entitled 'John Hardy,' and sung it on the scaffold before the execution. He was baptized the day before the execution. This last information I got from W. T. Tabor, who was deputy clerk of the Criminal Court at the time of the trial, and is now engaged in civil engineering. There is no record of the trial of John Hardy in the courthouse. Mr. Tabor informs me that there is no record of the trial in existence. The only thing I could find at the courthouse was the order for John Hardy's execution."

The following statement was given by Mr. W. T. Tabor [deputy clerk of the Criminal Court at the time of Hardy’s trail] to Mr. H. J. Grossman, principal of the High School at Welch, [WV]....

"John Hardy: Negro; about forty years of age; black in color; from Virginia; worked as miner in coal-fields; had no family as known; killed another Negro in a crap game over 75 cents; another Negro named Guggins helped him escape and tried to wrest gun from sheriff to shoot, but both men were captured and returned to Welch. Guggins was given a life term for attempt to kill sheriff.

The statement of R. L. Johnson, constable, who helped arrest Hardy, as compiled by Mr. Charles V. Price, shorthand reporter at Welch, W.Va., from a conversation between Johnson and Judge Herndon, was sent to me in the early part of the year 1917. It follows:—

"I was at Keystone the morning that Hardy killed this fellow, but I couldn't tell you the fellow's name now. They were shooting craps at Shawnee camp, and he was crap-shooting, and Webb Gudgin was behind a rock with a Winchester, and it is supposed that if Hardy didn't get the man that he was there with a Winchester to get him. After he was killed they sent to Keystone, and me and Tom Campbell went down there to search the camps; and while we were searching the camps they said, 'Yonder they go, down the road!' and we got on the railroad and followed them to the old bridge below Shawnee, and they turned up the hollow, and I says, 'We will follow them up there,' Tom says, 'No, we can't follow them in the woods; they have got a Winchester, as good a gun as we have got.' So we went back and decided to watch the trains. Me and some one, I think it was Harvey Dillon, was watching Northfork station. They got on the train at Grover, and they got them; and when they went to handcuff Hardy, Gudgin was walking through the coaches, and every one went out to get Gudgin, and he made to jerk John off the train; but John held to him till they got the train stopped, and they sent a colored fellow back there to help him, and they put him on the train and brought him back to Keystone. George Dillon and I took charge of him. John wasn't able to stay up. We took charge of them and guarded them that night, and they come and threatened to lynch him, and we said they couldn't come up there, and Webb said if we would unhandcuff him and give him his gun nobody would come up there. We had him over Belcher's store.

"I believe I come down the next morning and put them in jail. I never knew anything more about the case until the trial. I was down here during the trial. After he was found guilty he wanted to be baptized. We took him down there to the river, and I was along with him when they baptized him. I forget what preacher baptized him. He had on a new suit of clothes, hat and everything, but he didn't like the looks of his shoes at all. I took them back and swapped them; and when he put them on and viewed himself he had on the best suit he ever had, the way I looked at it, He was about six feet two, I think, or maybe he might have been six foot three."

Judge Herndon. Give his color, before you start on Gudgin.

Mr. Johnson. He was black.

Judge Herndon. About what age?

Mr. Johnson. Well, I couldn't hardly tell you. I would figure him about thirty.

Judge Herndon. Now give a description of Gudgin.

Mr. Johnson. Well, Gudgin, I believe, was a little taller than I am, I believe about six feet, heavily built. He wasn't so fleshy, but he was heavy built, yellow.

Judge Herndon. Were you deputy sheriff at the time?

Mr. Johnson. I was constable.

Judge Herndon. Campbell was deputy sheriff?

Mr. Johnson. Yes.

Judge Herndon. And John Effler was the sheriff of McDowell County at that time?

Mr. Johnson. Yes, sir.

Judge Herndon. In the town of Welch now do you know about the spot where the scaffold was built

Mr. Johnson. Why, I could get out here and look it up, but it was right out here somewhere.

Mr. David Collins. It was right back of the old temporary jail.

Judge Herndon. You say you don't remember the name of the man John Hardy killed?

Mr. Johnson. No, I don't remember him.

Judge Herndon. But do you remember what they killed him for?

Mr. Johnson. They were shooting craps. It is my understanding they had had the crap game before, and this fellow had skinned Hardy, and he went back and started the crap game to get to kill him. That was the statement at the time.

Judge Herndon. In other words, this colored man that Hardy killed had skinned Hardy in the game before that game?

Mr. Johnson. Yes, sir, and Hardy goes down and starts a crap game, and Webb was behind this rock with his Winchester so if Hardy failed he would get him. That was the statement, what they claimed when they came after us, when we went down there.

Judge Herndon. Where was he from?

Mr. Johnson. I don't know. I might have heard, but I never paid any attention. We were out nearly all night that night. I recollect it well. I think it was about the first year John Effler was elected sheriff. My. recollection is that the time Hardy killed the other colored man was along some time during the first of the year, in 1893, and that he was tried along about April or May, 1893, and hanged soon after his conviction, about sixty days.Note.—The following statement was made to me in person in the summer of 1918 by Mr. James Knox Smith, a Negro lawyer of Keystone, McDowell County, who was present at the trial and also at the execution of John Hardy:—

"Hardy worked for the Shawnee Coal Company, and one pay-day night he killed a man in a crap game over a dispute of twenty-five cents. Before the game began, he laid his pistol on the table, saying to it, 'Now I want you to lay here; and the first niggeer that steals money from me, I mean to kill him.' About midnight he began to lose, and claimed that one of the Negroes had taken twenty-five cents of his money. The man denied the charge, but gave him the amount; whereupon he said, 'Don't you know that I won't lie to my gun?' Thereupon he seized his pistol and shot the man dead.

"After the crime he hid around the Negro shanties and in the mountains a few days, until John Effler (the sheriff) and John Campbell (a deputy) caught him. Some of the Negroes told them where Hardy was, and, slipping into the shanty where he was asleep, they first took his shotgun and pistol, then they wakcd him up and put the cuffs on him. Effler handcuffed Hardy to himself, and took the train at Eckman for Welch. Just as the train was passing through a tunnel, and Effler was taking his prisoner from one car to another, Hardy jumped, and took Effler with him. He tried to get hold of Effler's pistol; and the sheriff struck him over the head with it, and almost killed him. Then he unhandcuffed himself from Hardy, tied him securely with ropes, took him to Welch, and put him in jail.

"While in jail after his conviction, he could look out and see the men building his scaffold; and he walked up and down his cell, telling the rest of the prisoners that he would never be hung on that scaffold. Judge H. H. Christian, who had defended Hardy, heard of this, visited him in jail, advised him not to kill himself or compel the officers to kill him, but to prepare to die. Hardy began to sing and pray, and finally sent for the Reverend Lex Evans, a white Baptist preacher, told him he had made his peace with God, and asked to be baptized. Evans said he would as soon baptize him as he would a white man. Then they let him put on a new suit of clothes, the guards led him down to the Tug River, and Evans baptized him. On the scaffold he begged the sheriff's pardon for the way he had treated him, said that he had intended to fight to the death and not be hung, but that after he got religion he did not feel like fighting. He confessed that he had done wrong, killed a man under the influence of whiskey, and advised all young men to avoid gambling and drink. A great throng witnessed the hanging.

"Hardy was black as a crow, over six feet tall, weighed about two hundred pounds, raw-boned, and had unusually long arms. He came originally from down eastern Virginia, and had no family. He had formerly been a steel-driver, and was about forty years old, or more."

What is the truth?

Above, we have a two discussions of the sources of the ballad “John Hardy was a Desperate Little Man”. One uses newspaper reports as sources. The other is a bit messier and relies on testimony of various individuals discussing events that happened 20 years before. The accounts don’t diverge much, but there are some details, such as where Hardy was captured, that vary across the telling.

Which account tells the accurate story? In most cases like this, I tend to believe that the truth lies somewhere in the middle of it all, and suspect to be the case here.

Did Hardy write the entire song as printed by Lomax? I doubt it.

Could Hardy have written it, or part of it? Sure. Anything’s possible. I’ll readily admit that I love the idea of an autobiographical song penned by its subject shortly before walking to the gallows, but I just don’t think it’s true. There are too many variables at play here.

A Peculiar Postscript

I’ll end our discussion of The Song on a tragic and strange note. We don’t know who wrote this song. We don’t know when it was written. We don’t even know the exact events of John Hardy’s capture. We only know that these were real people, that Hardy, a married man, killed Drews over a craps game, and that Hardy was hanged for the crime.

We also know what happened to John Hardy’s wife, Mary Hardy, after Hardy’s execution. According to an April 16 article from Huntington, West Virginia, in which she was identified as John Hardy’s widow, Mary Hardy was ambushed and shot about fifty miles south of Huntington while on her way home. No information was provided regarding the identity of her assailant(s), and we don’t even know exactly where the event took place. We only know that she was slain, The newspaper report ends with the words.

“She was a desperate character.”

I want to think there’s a connection. I want to believe this isn’t a coincidence. You know that, right? I want to believe that someone read the newspaper account of Mary Hardy’s murder, and borrowed the adjective from the final line of the article to compose a ballad about John Hardy.

As with the notion that the original version of this song was composed by its subject, my little fantasy about the songs authorship sounds cool, but there’s no way it can be proven.

The Performance

This performance features only two of the three Carters; Sara and Maybelle. While A.P. Carter contributed bass vocals to a number of Carter Family recordings, his appearances were sporadic and seem a bit arbitrary. This is not to diminish A.P. Carter’s contributions because I do believe the tracks on which he appeared were improved by his presence, but the truth is, Sara and Maybelle did the lion’s share of the work in the studio. A.P. may have arranged the pieces, but Sara and Maybelle were responsible for executing all of the instrumentation and most of the vocals on the original Carter Family recordings. No small feat.

This performance starts out with some amazing guitar work from Maybelle Carter. In this intro, she’s playing the “Carter scratch”, her signature style. When playing the Carter scratch, the melody line is played on the bass strings, while the higher strings are strummed. This technique was a groundbreaking development that went on to shape the sound of country music (and the countless offshoots of country music that have emerged since).

SIDEBAR: About the Carter Scratch

There are conflicting tales as to how the Carter scratch came into being. Some sources suggest she learned the technique from Lesley Riddle while others suggest she developed the style on her own. I don’t want to discount Riddle’s contributions. He played a tremendous role in the story of the Carter Family, and showed Maybelle quite a few things on guitar, (which I will cover in future installments), but Riddle didn’t encounter the Carters until 1928. The Carter scratch can be clearly heard in the Carter’s 1927 recordings. So, I’m of the opinion that it was Maybelle’s creation.

I did some digging for evidence to support my thinking, and cracked open Will You Miss Me When I'm Gone?: The Carter Family & Their Legacy in American Music by Mark Zwonitzer and Charles Hirshberg. The chapter titled “Maybelle” indicates that she learned banjo from her mother when she was about 12 years old, and picked up guitar around age 13. At the time, guitar was a relatively new instrument in rural music, and when Maybelle adapted the banjo picking style to the guitar, she created a whole new style of guitar playing. The text includes the following quote from Maybelle on the creation of her style

"I started trying different ways to pick it, and came up with my own style, because there weren't many guitar players around. I just played the way I wanted to, and that's it."

Because the Carter scratch appears on the very first side that the Carter Family cut in 1927, opens this recording from 1928, and continues to appear in the same fundamental form throughout the Carter Family’s catalog, I’ll ride with Maybelle Carter’s account.

Back to the Performance

This is one of those songs where it’s difficult to put into words exactly what qualities make it so appealing, but I’m gonna try. To start, Maybelle delivers this spectacular demonstration of the Carter scratch while Sara’s autoharp fleshes out the chords. When Sara Carter’s clear, pure, (and very country) voice rings out, the story begins.

We’ve gone over the lyrical content of the song already, and if you listen simply to the sound of the song, you can tell that this is a thoroughly rehearsed piece. Sara and Maybelle both have incredible timing, and the interplay between the guitar and autoharp is exquisite, with the instruments remaining tightly synchronized throughout the nearly three minute recording. This tight groove is not a quirk. It is the result of serious focus and a lot of practice.

As I’ve mentioned, the way Sara’s autoharp plays off Maybelle’s guitar is fantastic, and it persists throughout the recording. The tempo of this song is unforgiving, and leaves very little room for mistakes by either musician. But I don’t hear any mistakes on this recording anyway. Sara and Maybelle are locked in throughout the song.

With each word she sings, Sara’s vocals are matched with Maybelle’s spot on guitar melody notes all the way through the song. The more I think about it, the more impressed I am with this performance. The tempos at which it’s played makes it all the more impressive. It’s quick, and the duo rip right through it, each playing a whole lot of notes, but never falling out of sync.

Is it the most impressive display of musical skill we’ve encountered so far on our journey through the Anthology? Maybe so… maybe not, but yeah, probably.

The Performers

PROGRAMMING NOTE: The Carter Family are a very big deal, and they appear four times in the first three volumes of the Anthology. My recounting of their story will take place across the first three articles about their recordings. This first installment will discuss their backgrounds and lives up through the 1928 recording sessions from which this recording emerged. The second installment (“Engine 143” on Side D of Volume One - Ballads), will introduce Lesley Riddle and discuss the Carter Family’s career from 1928 to 1936. The third (“Little Moses” on Side D of Volume Two - Social Music) will explore events after 1936. The final Carter Family song to appear on the Anthology (“Single Girl, Married Girl” in Volume Three - Songs) was recorded at the Bristol Sessions, and is the only Carter Family song on the Anthology that was recorded in a session supervised by Ralph Peer. In that article, rather than exploring the Carter Family further, “The Performers” section will feature a look into the life, work, and influence of Ralph Peer,

Our story begins in Maces Springs, Virginia, a rural community in Poor Valley of the Clinch Mountain, and home to A.P. (Alvin Pleasant) Delaney Carter (b. 1891). Carter was a peculiar guy. He had a bit of a tremor (that his mother attributed to a nearby lightning strike while she was pregnant with him. This tremor can even be heard in his voice, now that you know to listen for it.

He married Sara (Dougherty) Carter (b.1898), and his brother Ezra “Eck” Carter (b. 1898) lived nearby with his wife Maybelle (Addington) Carter (b. 1909). Together, they made up the First Family of Country Music, the Carter Family.

In the group, A.P. was the song collector, manager, and occasional vocalist. Sara was the primary vocalist, and also played autoharp and guitar. Maybelle Carter was the primary guitarist and also contributed harmony vocals. Ezra neither played nor sang, but it was Eck’s car that took A.P., Sara, the pregnant Maybelle, plus Gladys and Joe (the oldest and youngest of A.P. and Sara’s three children) to Bristol for their 1927 recording sessions.

Ads like the one above appeared in newspapers near the Bristol, TN area prior to the Bristol Sessions. The Carters made music at home, and A.P. was convinced that Sara and Maybelle were something special. They’d been heard by a scout from Brunswick who didn’t record them because he didn’t think a female lead would sell., but he encouraged Sara to keep singing. Once he saw this advertisement, A.P. Carter made arrangements for himself, Sara, and Maybelle to audition for Victor during these sessions.

While it would make for a great story to say that the Carters just showed up unannounced and blew Ralph Peer out of the water, that’s not exactly how it went down. A.P. had corresponded with Peer prior to the Bristol sessions, and arranged to be a part of the sessions in advance. So, prior to their arrival Peer knew of the Carters, and was expecting them. They were listed in his appointment book as “Mr. and Mrs. Carter from Maces Springs”, but no manner of description offered by A.P. could have possibly prepared Ralph Peer for what the Carter Family had in store.

The Bristol Sessions took place in a makeshift studio constructed on the third floor of the Taylor-Christian Hat and Glove Company on State Street, in Bristol, Tennessee, (a street so named because it runs along the Tennessee/Virginia state line such that one side of the street is in Tennessee, and the other in Virginia). At 6:30PM on August 1, 1927, the Carter Family entered Peer’s studio for their first scheduled recording session. In the three hours that followed, the trio recorded four sides. Bury Me Under the Weeping Willow, Little Log Cabin by the Sea, The Poor Orphan Child, and The Storms are on the Ocean. They returned the next day and recorded two more sides: Single Girl, Married Girl (which will appear later in the Anthology), and The Wandering Boy.

I’ve embedded “Bury Me Under the Weeping Willow” below so you can listen to the first track the Carter Family ever recorded while you read. This recording features all three Carters on vocals, Sara on autoharp and Maybelle on guitar.

In 1959, Peer did a series of interviews with Lillian Borgeson. In one interview, he recounted his first impressions of the Carter Family.

They wander in, he’s dressed in overalls and the women are country women from way back there - calico clothes on- the children were poorly dressed.. They were backwoods people and they were not accustomed to being in town, you see. They didn’t know what to do… But as soon as I heard Sara’s voice, that was it. You see, I had done this so many times that I was trained to watch for the one point… As soon as I heard her voice, why I began to build around it and all the first recordings were on that basis.

While this recounting is quite the “Sophisticated Bigshot Record Producer Guy meets country bumpkins, and transforms them into superstars” accounting of events, one thing shines above the bluster; Peer recognized the Carters as a unique and potent musical force, even though he couldn’t have possibly fathomed the magnitude of his discovery at the time.

The August 2 session took place in the morning, and that afternoon, the Carters were headed back to Maces Springs, having earned $300 for the six recordings, with the potential for royalties…. provided that the recordings were released.

In October 1927, the first batch of records from the Bristol sessions was released, and much to A.P.’s chagrin, the Carter Family recordings were absent from that initial group. In early November 1927, the Carter Family’s first 78 was released, containing “The Wandering Boy” backed with “The Poor Orphan Child”. Eck and Maybelle returned from a trip to Bristol with news of the record’s release, and copies of the record so they could hear themselves on the record player.

In early 1928, the Carters’ second 78, containing “The Storms are On the Ocean” backed with “Single Girl, Married Girl”, was released. We don’t have exact sales figures from 1928, but the record was a smash hit, and the Carters’ lives were permanently transformed. With their single flying off the shelves in the spring of 1928, Peer contacted the Carters and asked them to get to Camden, NJ as quickly as possible for a follow-up recording session.

Southern Music Publishing Co. Inc.

We’ll talk a lot more about Peer in later installments of this series, but for now, it’s important to know that on January 31, 1928, Peer started the Southern Music Publishing Co. Inc. Through Southern Music (known as Peermusic these days), Peer made publishing agreements with songwriters (and song collectors) like Carter for their compositions or arrangements. Through these publishing agreements, songwriters and/or arrangers received royalties for sales of their recordings and/or music. Of course, Southern Music Publishing got a cut, because that’s how publishing works, but it did give these artists a possible revenue stream that they wouldn’t have otherwise enjoyed.

Previous articles of Anthology Revisited have discussed how artists received no payments beyond what they received when the recordings were made. Peer’s publishing arrangements were new for hillbilly music, and gave performers the opportunity to money from their compositions, arrangements, and recordings beyond the initial compensation they received at they recording session. While Peer’s publishing agreements certainly leaned in his favor (rather than the artist’s), it was far better than making nothing at all. A.P. Carter saw this as an opportunity to make more money.

The 1928 Sessions

Carter was aware of Peer’s publishing agreements, so when asked to go to Camden and record, Carter selected songs for which he would be able to get songwriter or arranger credits. The Carters rehearsed and prepared a dozen songs for their trip to Camden, working out their parts and ensuring that the timing for each song remained under three minutes.

After the train ride to Camden, they spent the night in a hotel where they had their first encounter with such amenities as running hot and cold water. On May 9, they were picked up and taken to the Victor Recording Studio where they recorded a dozen sides over two days that would further cement their place in music history. On the first day, they recorded “Meet Me By Moonlight, Alone”, “Little Darling Pal of Mine”, “Keep on the Sunny Side” and “Anchored in Love”. On May 10, they returned to lay down seven sides: “John Hardy was a Desperate Little Man”, “I Ain’t Goin’ to Work Tomorrow”, “Will You Miss Me When I’m Gone”, “River of Jordan”, “Chewing Gum”, “Wildwood Flower”, “I Have No One To Love (But the Sailor on the Deep Blue Sea)”, and “Forsaken Love”. All twelve sides were released, and would have a seismic impact. Two of those songs (“Wildwood Flower” and “Keep on the Sunny Side”) became staples of the Carters’ repertoire, and are songs with which the Carters are closely identified to this day.

At some point during this visit, A.P. Carter signed the papers and entered into an artist-manager agreement with Peer. From this point forward, Carter received either songwriter or arranger credits for each song, and all the songs were published by Peer’s Southern Music (even if, like “Keep on the Sunny Side”, they were already published by another company).

When Carters left New Jersey to return to Maces Springs, they had made a dozen new recordings and were leaving with $600, and promises of royalties and future recording sessions. Their days of hardscrabble living were quickly falling behind them.

(And this is where we wrap up this week’s discussion of the Carter Family. We’ll dive back into the story in a few weeks when we get to “Engine 143”. )

Connections

The primary theme in this section of the Anthology of American Folk Music is the Timeline, and this is the sixth song in that section. To review, here are the songs in the Timeline, and the years in which their events are alleged to have occurred.

12 - Peg And Awl (1801-1804)

13 – Ommie Wise (1807)

14 – My Name Is John Johanna (1870’s)

15 – Bandit Cole Younger (1870’s; key event - 1876)

16 – Charles Giteau (1881-1882)

17 – John Hardy Was A Desperate Little Man (1893-1894)

This is our fifth consecutive song to feature someone’s name in the title, the third song in a row once purported to have been written by its subject, and the second consecutive song about a man convicted of murder, who finds religion in prison, but still ends up dying on the gallows.

This is the seventh of eight songs to feature a string ensemble of some sort, and the first to feature an autoharp (Harry Smith claimed “Old Shoes and Leggins” included an autoharp, but the instrument isn’t listed in the DAHR entry for the song, and while I will confess to having significant hearing loss, I cannot hear (and have never heard) an autoharp on that song).

Speaking of firsts, this is the first song on the Anthology to feature lead vocals by a female performer, and the first song on the Anthology to be performed exclusively by women.

I’m sure I’ve missed something.

Other Interpretations

This section examines other recordings of this same song, performed by other artists. Whenever Smith’s notes include a Discography, this section is divided into two segments, “Discography”, which examines Smith’s selections, and “Further Interpretations”, wherein the selections are left to my judgment.

Discography

Buell Kazee - John Hardy - Our old pal Buell Kazee recorded this version of John Hardy back in 1927 for Brunswick records. The lyrics to this one are slightly different, but tell basically the same story.

Eva Davis - John Hardy - The first recording of “John Hardy” was made on April 22, 1924 in New York City for Columbia records featuring Eva Davis on vocals and Samantha Bumgarner on banjo. (NOTE: The image in the video below is of Ms. Bumgarner (the instrumentalist), not Ms. Davis)

Clarence Ashley - Old John Hardy - Harry’s Discography includes this recording by Clarence Ashley (another name familiar to readers of Anthology Revisited). This version gives different details from the other versions, but includes direct reference to the Shawnee camp.

Further Interpretations

Leadbelly - John Hardy - This is the same song as performed by the Carter Family, and the intro shows that Leadbelly was influenced by the Carter scratch. If you’re a fan of Leadbelly’s recordings, you won’t be disappointed with this. It’s Leadbelly doing t

Leadbelly - John Hardy (accordion) - Leadbelly isn’t exactly known as an accordionist, and since this exists, I figured it would be fun to share.

Doc Watson and Earl Scruggs - John Hardy - Not sure when this was recorded, but it is magnificent. Two legendary performers playing together, accompanied by their sons. There’s some extra footage after John Hardy, which isn’t relevant to this, but is still pretty good stuff.

Bob Dylan and the Grateful Dead - John Hardy Was a Desperate Little Man - (Club Front Rehearsals, San Rafael, CA June 1987) - In the summer of 1987, the Grateful Dead and Bob Dylan did a short tour where the Grateful Dead were Bob Dylan’s backing band. The concerts themselves were cool, but not nearly as cool as the idea of the concerts.

The concerts didn’t live up to the potential of the pairing, but these widely bootlegged, but never officially released tour rehearsals, are pure gold for fans of Dylan and the Dead, giving an extended peek behind the curtain as they work through a wide array of songs together in preparation for the tour.

Bill Frisell - John Hardy Was Desperate Man - an instrumental take on the song from 2002. Frisell is a great jazz guitarist, and the album from which this comes (Frisell’s 2002 “The Willies”) contains his takes on a number of traditional tunes. This has a completely different feel from all the other recordings, and offers a darker, more brooding interpretation of the tune.

Billy Strings - John Hardy - Live April 15, 2025 - Our final entry in the John Hardy list is also the most recent performance, recorded mere months before this article was written. Over the past few years, Billy Strings has taken the American roots music world by storm. His rise has been rapid, but fully justified. He’s an exceptional instrumentalist and a gifted vocalist with a deep appreciation of the music’s history. I love what he’s doing, and am thrilled to see these songs being performed for new audiences.

Conclusion

As usual, we’ve covered a whole lot of ground in this installment, and my head is still sorta spinning over which source (if any) tells the real story of John Hardy. Newspaper reports differ from eyewitness accounts, and the changes in details across versions of the song’s text (which should never be considered entirely factual) only make things murkier. It’s impossible to know the full and true story of Hardy, but hopefully you’re walking away with a little better understanding.

Meanwhile, the connections between songs keep on piling up. We’ve been on a roll for a bit, riding on this Timeline theme with the recurring sub-theme of Titular Characters. But our next installment is gonna shake up our themes a little bit, but we’ll get to that when we get to that. For now, just know that our next installment of Anthology Revisited will feature “Gonna Die with My Hammer in My Hand” by Williamson Brothers and Curry, a song about an American Legend whose name has appeared more than once in this very article.

In closing, as I always do, I must mention that I’m merely gathering information that exists and presenting it to you. I didn’t come up with any of this stuff on my own. I’m building upon the work of previous researchers, and if you’d like to learn more about John Hardy or the Carter Family, the sources I consulted follow the author’s notes below.

AUTHOR’S NOTES: This Substack is a one-man operation. Anthology Revisited is a labor of love. I am an independent writer, hoping to create a work of substance and contribute something of value to the ongoing conversation. Your likes, restacks, and comments are tremendously appreciated. If you want to support my work (or contact me beyond the comments section), there are a few options.

You can subscribe to this Substack. You’ll receive these articles in your inbox, and all you have to do is click the “Subscribe now” button below and enter your email address in the box that appears.

You can pass this article along to someone else who might like it via the “Share” button. I really hope you’ll do this. I know there’s an audience for this, I just don’t know where to find them. If you know a person or group of folks who might find this interesting, kindly pass this article along, and together, we’ll find the niche into which this fits.

This article is part of a series called Anthology Revisited, which is part of my publication, Rodney Writes about Music. To share this whole shebang with others, click the “Share Rodney writes about music” button below. (If you share the publication, the link will point to the landing page, where the introductory article for Anthology Revisited is prominently featured.)

I suck at asking for money, and I don’t have paid subscriptions enabled at the moment. If you’d like to chip in to the “help Rodney keep the lights on” fund, click the “Buy Me a Coffee” button.

If you’d like to offer any corrections to my content or contact me regarding Anthology Revisited, email me directly at rodney.hargis at outlook.com.

Sources

John Hardy (song) - Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Hardy_(song)

Murder Ballad - John Hardy Was a Desperate Little Man

https://kidnappingmurderandmayhem.blogspot.com/2008/06/murder-ballad-john-hardy-was-desperate.html

On American Pastimes: In the end John Hardy wasn’t a desperate little Man

http://kzfr.org/broadcasts/25273

John Hardy attributed his downfall to whiskey - Appalachian History

https://www.appalachianhistory.net/2019/01/john-hardy-attributed-his-downfall-to.html

John Hardy - The Genesis of a Song | No Depression

https://nodepression.org/john-hardy-the-genesis-of-a-song/

John Hardy [Laws I2]

https://web.archive.org/web/20131202232717/http://www.fresnostate.edu/folklore/ballads/LI02.html

Folk Songs of North America

Lomax, Alan

p. 265 141. John Hardy

Doubleday and Company, Inc. 1960

Garden City, NY

Journal of American Folk-Lore, Volume 32, No. 126

John Hardy

Cox, John Harrington

October-December 1919, pp.505-520.

https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/John_Hardy

Bristol sessions - Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bristol_Sessions

About the Sessions | The Bristol Sessions

https://web.archive.org/web/20180821135648/http://bristolsessions.com/about/

The Sessions | Birthplace of Country Music

https://web.archive.org/web/20101119203151/https://birthplaceofcountrymusic.org/node/33

Victor Talking Machine Company sessions in Bristol, Tennessee--The Carter Family, Jimmie Rodgers, Ernest Stoneman, and others (1927)

Ted Olson, 2002

https://www.loc.gov/static/programs/national-recording-preservation-board/documents/Bristol.pdf

AP Carter | Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame

https://nashvillesongwritersfoundation.com/Site/inductee?entry_id=1313

Will You Miss Me When I'm Gone?: The Carter Family & Their Legacy in American Music

Zwonitzer, Mark; Hirshberg, Charles

Simon and Schuster, 2002

New York, New York

Carter Family - Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carter_Family

Carter Family picking - Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carter_Family_picking

A.P. Carter - Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A._P._Carter

Ezra Carter - Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ezra_Carter

Maybelle Carter - Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maybelle_Carter

Sara Carter - Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sara_Carter

Carter Family - Discography of American Historical Recordings

https://adp.library.ucsb.edu/index.php/mastertalent/detail/103002/Carter_Family?Matrix_page=100000