My Name is John Johanna by Kelly Harrell and the Virginia String Band [Anthology Revisited - Song 14]

TL;DR -- Historic (prophetic) song exposes man’s inhumanity to man. Previously uncredited fiddler returns, remains uncredited.

Welcome back to the fourteenth installment of Anthology Revisited, our song-by-song journey through the Anthology of American Folk Music, compiled by Harry Smith and released on Folkways Records in 1952.

This time, we’ve got a song about poor folks being lied to, misled, and mistreated. “My Name is John Johanna” was recorded for Victor Records in Camden, New Jersey on March 23, 1927 by Kelley Harrell and the Virginia String Band.

(NOTE: While the record labels show his name as “Kelly Harrell”, his name is spelled “Kelley” on official documents and his tombstone, so that’s what I’m sticking with.)

“My Name is John Johanna” is the final song on the first LP of Volume One - Ballads in the Anthology of American Folk Music, and it echoes themes that have emerged throughout side two.

While neither courtship nor murder appear, betrayal (in this case, promising one thing and delivering something else) is front and center, and at its core, it’s a song about our species’ ongoing penchant for casually mistreating one another for personal gain.

The song takes place in the years after the Civil War, and is not a description of any specific man’s personal experience, but rather serves to describe the exploitative labor practices that were the norm in the years following the Civil War. We don’t have a specific year to which we can tie the events of this song, but the conditions described could have been at nearly anytime in the 1870’s.

Despite my grim introduction, this is actually a humorous little number, in a sad sort of way, and we’ll get to playing it in just a second, but first, let’s check out Harry’s headline for this one.

DITCH DIGGER SHOCKED BY EMPLOYMENT AGENTS’ GROTESQUE DECEPTIONS

It’s a pretty accurate description of the song’s events. This headline doesn’t say anything about Johanna’s arrival in or departure from Arkansas. Instead, Smith gets right to the heart of the song. This is what we’ve got. A fellow who was hired to dig ditches is stunned by the horrific working and living conditions. What Smith’s headline fails to capture is how the song somehow manages to vividly describe this inhumane scenario while simultaneously making light of the situation.

Give it a listen, and you’ll see what I mean. Again, it’s “My Name is John Johanna”, performed on March 23, 1927 in Camden, NJ by Kelley Harrell and the Virginia String Band.

Lyrics

My name is John Johanna. I came from Buffalo town.

For nine long years I've traveled this wide, wide world around

Through ups and downs and miseries, and some good days I saw,

But I never knew what mis'ry was ‘til I went to Arkansas.I went up to the station, the operator to find,

Told him my situation and where I wanted to ride.

Said: "Hand me down five dollars, lad. A ticket you shall draw

That'll land you safe by railway in the state of Arkansas."I rode up to the station, the chance to meet a friend.

Alan Catcher was his name although they called him Cain.

His hair hung down in rat tails below his under jaw.

He said he run the best hotel in the State of Arkansas,I followed my companion to his respected place,

Saw pity and starvation was pictured on his face.

His bread was old corn dodgers*. His beef I could not chaw.

He charged me fifty cents a day in the State of Arkansas.I got up that next morning to catch that early train.

He says: "Don't be in a hurry, lad. I have some land to drain.

You'll get your fifty cents a day and all that you can chaw.

You'll find yourself a different lad when you leave old Arkansas."I worked six weeks for the son of a gun. Alan Catcher was his name.

He stood seven feet two inches, as tall as any crane.

I got so thin on sassafras tea, I could hide behind a straw.

You bet I was a different lad when I left old Arkansas.Farewell, you old swamp rabbits, also you dodger pills,

Likewise you walking skeletons, you old sassafras hills,

If you ever see my face again, I'd hand you down my paw.

I'd be looking through a telescope from home to Arkansas.

TERMS

corn dodgers - a type of cornbread made from corn meal, pork fat, salt, and boiling water. The ingredients were mixed, shaped into small loaves and baked.

dodger pills - the small corn dodger loaves were sometimes referred to as ”pills”.

sassafras - an aromatic tree native to the eastern half of North America historically used for seasoning and medical treatments. Sassafras root is used to make root beer, and its leaves are used to make filé powder, a seasoning used in gumbo and other Creole dishes.

sassafras tea - prior to the second half of the 20th century, sassafras tea was touted as a cure-all, and used as a tonic to purify the blood and treat problems including gout, syphilis, arthritis, sore throat, and cancer. In the 1970’s, safrole (a compound found in sassafras root) was discovered to cause liver cancer, and its sale and use have since been regulated.

swamp rabbit - the largest breed of cottontail rabbit, native to swamps in the southeastern United States. Unlike most rabbits, swamp rabbits will readily go into water.

The Song

There are countless real-world tales of people to whom one thing has been sold and another delivered. In the modern world of ubiquitous advertisements, such betrayals are commonplace, and most folks know that advertisements cannot be trusted.

Falling for false advertisements can have dire consequences, even in this modern age, where one the next fraud or scam is but a click away. In the late 1800’s, things weren’t too different, and while no one had their online accounts hacked and identities stolen, folks’ lives could be quickly turned upside down by placing their trust in the wrong advertisement.

That’s what happened to John Johanna, a self-proclaimed world traveler who believed he was starting a new life in Arkansas, only to realize he’d been misled.

We aren’t told why, where, how, or by whom John Johanna was encouraged to head to Arkansas, but it’s pretty clear that he headed down there looking for work, and was told he’d be taken care of. Although Johanna claims to meet a “friend” named Alan Catcher at the train station, it’s not clear when this friendship began, but I suspect it originated at the depot.

Regardless of how long he’d known Catcher or who sent him to Arkansas, it’s evident that Johanna was lured to the Land of Opportunity with the promise of work and prosperity, but arrived to find the situation far less appealing than advertised.

Unlike our previous two songs (“Peg and Awl” and “Ommie Wise”), which provided a time period by stating the year, or referencing an actual historical event, “My Name is John Johanna” doesn’t explicitly state the period in which it takes place. However, the song gives us enough information to place it within a rough time frame.

After the U.S. Civil War, railroads were being constructed across the south, and laborers were needed to help in the massive construction projects, which involved clearing and leveling land and digging ditches, so as to clear the path for the tracks to be laid down The word of employment opportunities spread far and wide, flyers were printed, and members of immigrant communities in particular were recruited to places like Arkansas to perform this labor. This was necessary work, but the railroad companies of the late 19th century rarely provided adequate food or shelter for the workers, hence the horrid conditions that Johanna discovered.

Harrell’s is the first known recording of the song, which has been dated to the late 1800’s. Several historians and folklorists have dated the song to as far back as the 1870’s, which, historically speaking, would fit with the events of this song.

A variant of this song, called “The State of Arkansas” was recorded by I.G. Greer, and includes lyrics which indicate the events took place in 1852, even though the first railroads in Arkansas weren’t chartered until 1853. This same variant also includes a reference to Abraham Lincoln, who wasn’t a household name in 1852. The recording is not available online, but the lyrics to this variant can be found in the Discography subsection of the Other Interpretations section of this article.

An Irish Source?

Despite the 1852 reference in Greer’s variant, the general agreement is that the song originated in the decades after the American Civil War. There is no definitive original version of the song, but folklorists and scholars have come to believe that it first appeared some time between 1870 and 1890.

A possible source for “My Name is John Johanna” could very well be “The Spalpeen’s Complaint to the Cranbally Farmer”, an Irish folk song with similar sentiments that was published in a collection assembled by Patrick Weston Joyce in 1909.

“My Name is John Johanna” is by no means a line-by-line or verse-by-verse rewrite of the song, but there are significant similarities. Joyce’s introductory text for the song and the lyrics are below, so you can judge for yourself.

406. THE SPALPEEN'S COMPLAINT OF THE CRANBALLY FARMER.

I have endeavoured to give representations of all classes of Irish Folk Songs in this collection; and the two following ballads represent — well and vigorously — the satirical class. Both have remained in my memory since my boyhood ; and I have a copy of " The Cranbally Farmer " on a roughly-printed sheet. This same "Cranbally Farmer" — the man himself — was well known in the district sixty years ago as a great old skinflint ; and the song drew down on him universal ridicule….

Spalpeens were labouring men — reapers, mowers, potato-diggers, etc. — who travelled [sic] about in the autumn seeking employment from the farmers, each with his spade, or his scythe, or his reaping-hook. They congregated in the towns on market and fair days, where the farmers of the surrounding districts came to hire them. Each farmer brought home his own men, fed them on good potatoes and milk, and put them to sleep in the barn on dry straw — a bed — as one of them said to me — "a bed fit for a lord, let alone a spalpeen."

One evening of late as I happened to stray

To the County Tipprary I straight took my way

To dig the potatoes and work by the day

I hired with a Crabally farmer. I asked him how far we were bound to go

The night it was dark and the north wind did blow

I’m hungry and tired and my spirits as low

I have neither whiskey nor cordial

He made me no answer but mounted his steed,

To the Cranbally mountains he posted with speed ;

I certainly thought my poor heart it would bleed

To be trudging behind that old naygur*

When I came to his cottage I entered it first;

It seemed like a kennel or ruined old church :

Then says I to myself, " I am left in the lurch

In the house of old Darby O'Leary."I well recollect it was Michaelmas night,

To a hearty good supper he did me invite,

A cup of sour milk that would physic a snipe —

Your stomach ‘twould put in disorder

The wet old potatoes would poison the cats,

The barn where my bed was was swarming with rats,

'Tis little I thought it would e'er be my lot

To lie in that hole until morning.By what he had said to me I understood,

My bed in the barn it was not very good ;

The blanket was made at the time of the flood ;

The quilts and the sheets in proportion.

'Twas on this old miser I looked with a frown,

When the straw was brought out for to make my shake down ;

I wish that I never saw Cranbally town.

Or the sky over Darby O'Leary.I worked in Kilconnell, I worked in Kilmore,

I worked in Knockainy and Shanballymore,

In Pallas-a-Nicker and Sollohodmore,

With decent respectable farmers :

I worked in Tipperary, the Rag, and Rosegreen.

At the mount of Kilfeakle, the Bridge of Aleen,*

But such woeful starvation I've never yet seen

As I got from old Darby O'Leary.

https://archive.org/details/oldirishfolkmusi00royauoft/page/216/mode/2up

The Performance

Kelley Harrell never played an instrument. While not unheard of, it was uncommon for string bands to have a dedicated vocalist. Harrell could pull it off because he was an exceptional vocalist. There’s no video evidence to back me up on this, but to my ear, Harrell’s phrasing and delivery suggest a performer with plenty of confidence and natural charisma on stage.

The musicians backing Harrell on this track are Posey Rorer (fiddle), Alfred Steagall (guitar) and R.D. Hundley (banjo). Steagall and Hundley recorded with Harrell on March 22 and 23, 1927 and again on August 12, 1927. Steagall recorded with Harrell again in 1929. Ralph Peer was the session supervisor for all of Harrell’s 1927 sessions.

When I listen to this recording, the opening clearly shows Posey Rorer leading the way, with Steagall and Hundley following his lead. Both men are a bit out of step with Rorer to start the track, but they correct course quickly, and establish a stable rhythmic backing for Harrell’s vocals. With Rorer’s fiddle playing the melody line, it’s as if Harrell’s vocals hop right on, and simply glide through the song. The precision with which Rorer’s fiddle accompanies Harrell’s vocal is splendid to this ear.

The tale progresses for several verses until this super cool whistling / banjo instrumental break comes in. At the break, the guitar and fiddle go silent, and the banjo sticks with the main theme. Harrell’s whistling and Hundley’s banjo do a fun little dance with one another. When the break ends, Rorer and Steagall return to the action right on time, and we’ve got a smooth ride through the final verses to the end.

The Performers

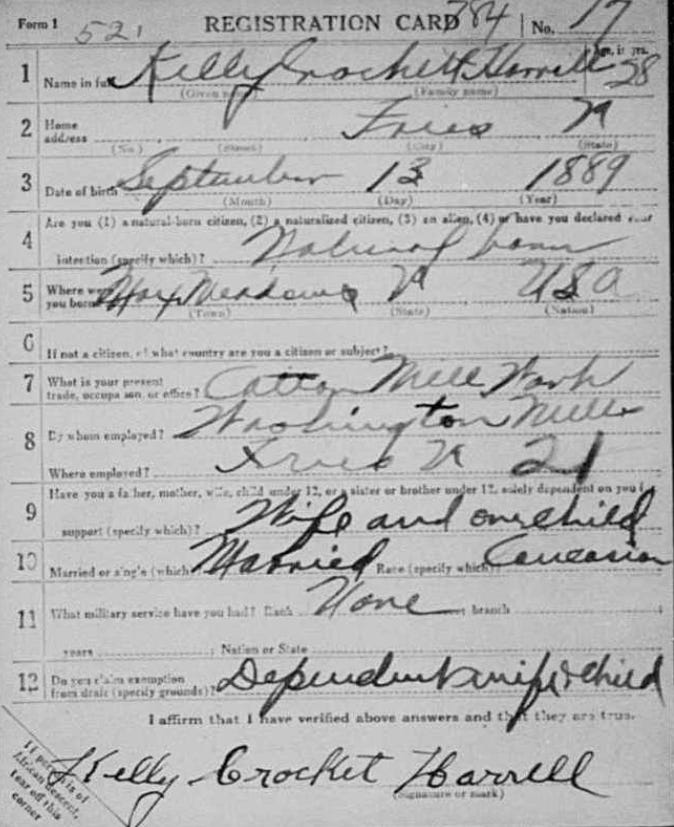

According to his World War I Draft Card, Crockett Kelley Harrell was born on September 18, 1889 in Max Meadows, Wythe County, Virginia, in the Appalachian mountains. (NOTE: Some sources list Harrell’s place of birth as Draper’s Valley, VA which is near Max Meadows).

In 1894, the Harrell family still lived in the Wythe County area, but a few miles east of Max Meadows in Graham Forge, Virginia. At some point between 1894 and 1910, the family moved to Fries, Virginia.

While I can’t confirm it, one would suspect their move to have taken place in or after 1903, when the Washington Cotton Mill opened in Fries, VA.

We know definitively that the family was in Fries, VA on April 16, 1910, because the US Census paid them a visit on that date. At that time, the 20 year old Kelley Harrell lived with his parents William (age 54) and Barbara (51), his sister Delia (18), and his brothers James (24), Gilbert (15), and Sidney (13). With the exception of Kelley’s mother Barbara, each member of the Harrell household worked in the Washington Cotton Mill.

The younger boys worked as doffers, removing the doffs filled with spun fiber from the spinning machine and replacing them with empty ones. The work required more speed than strength, and the young boys were perfect for the job. (Meanwhile, the law required doffers to be at least 14 years old. According to the US Census Bureau, Sidney was 13 years old and a doffer at the mill. So, there’s that.)

By 1912, Harrell moved south to the Old Town area of Grayson County, VA. This area will be familiar to regular readers of Anthology Revisited, as we’ve mentioned this rural location a couple of times already in this series, first when we discussed Uncle Eck Dunford (11 - “Old Shoes and Leggins”), and G.B. Grayson and Henry Whitter (13 - “Ommie Wise”). We’ll return to Old Town a few more times before this series is complete.

On June 3, 1912, Harrell married Mary Lula Carico in Edmonds, NC (which is in Alleghany County, just south of the NC/VA border). On May 2, 1913, while the couple was living in the Old Town district of Grayson County, VA, Mary Harrell gave birth to their daughter, Ruth Harrell. Harrell’s World War I draft card, (from 1917) lists him working in the Washington Mills cotton mill in Fries, Virginia, and describes him as being of medium height with stout build, grey eyes, and black hair.

In either 1919 or 1920, the Harrell’s had a son, Eugene. When the census was taken in Old Town on June 2, 1920, Eugene Kelly Harrell was listed with an age of “4/12”, suggesting he was four months old. However, Eugene’s tombstone indicates he was born on August 23, 1919.

The same US Census record gives us a little bit more information about Kelley Harrell, indicating that he worked as a loom fixer in the cotton mill, giving us a tiny peek into what his day-to-day life was like.

According to Kinney Rorrer’s book “Rambling Blues: The Life and Songs of Charlie Poole”, Harrell and his family left Grayson County, and moved roughly 75 miles east to Fieldale, VA in 1924. In Fieldale, Harrell met Alfred Steagall and R.D. Hundley, who also played on this recording.

We’ll pick up Kelley Harrell’s story (and look into the stories of Steagall and Hundley) when we get to “Charles Giteau”.

The Posey Rorer Story (Part 2)

Posey Rorer has already appeared in Anthology Revisited on track 11, “A Lazy Farmer Boy”, and in that article, I discussed a little bit about Rorer, and mentioned that we’d fill in some more blanks about his life story as we went along. “A Lazy Farmer Boy” (from 1931) was among Rorer’s final recordings, and this recording with Kelley Harrell was made a few years prior in 1927.

By the time Rorer recorded with Harrell, he had made a name for himself as the fiddler with Charlie Poole and the North Carolina Ramblers, with whom he’d recorded in 1925 and 1926. The recording session with Harrell (March 23, 1927) was Rorer’s first recording session without Charlie Poole (though it would hardly be his last).

Harrell didn’t play an instrument, and his earlier recording sessions were with studio musicians. He was unhappy with the results, feeling they lacked the authenticity of a genuine Virginia string band. So, when Harrell returned to Victor’s Camden, NJ studio on March 22, 1927, he brought Rorer, Alfred Steagall, and R.D. Hundley. These sessions, which yielded 9 sides for Victor, included both of the Harrell recordings that appear on the Anthology, “My Name is John Johanna”, and “Charles Giteau” (song 16 on the Anthology). After this session, Posey Rorer went on to record with Roy Harvey on May 11, and 12 1927 in New York City for Columbia records.

Later that year, on September 22, Rorer switched things up and played mandolin on 6 sides with Frank Miller and Matt Simmons that were recorded for Okeh Records in Winston-Salem, NC. Of those recordings, only two “Childhood’s Sweet Home” and “That Little Old Hut” are known to have been released.

(NOTE: The links in the previous paragraph point to the Discography of American Historical Recordings (DAHR) pages for each song and include audio. It’s quite cool to hear Rorer play something other than fiddle, and, not surprisingly, he does it quite well.)

In February 1928, Rorer, along with Roy Harvey and Bob Hoke, recorded 10 sides for Brunswick Records in Ashland, Kentucky, which were released under the name the “Roy Harvey and the North Carolina Ramblers”. For a sample of that version of the NC Ramblers, check out this recording of The Bluefield Murder. Rorer’s fiddle is unmistakable.

In 1928, Rorer, Miller, and Simmons went to the Edison Recordings studios in New York City, and between September 22 and September 25 recorded 25 sides. Unlike the 1927 sessions where Rorer played mandolin with Miller and Simmons and didn’t get credit on the label, these recordings were attributed to “Posey Rorer and the North Carolina Ramblers”.

Not only were these recordings available on 78 RPM releases, they were also sold on the cylinder records (a format that preceded 78’s). Cylinder preservationists have digitized these recordings and uploaded them to YouTube. For a sample, check out this cylinder for “Down in a Georgia Jail” recorded in those sessions. (Note: the music at the very beginning is theme music from the preservationists, not part of the song)

As you can tell, the North Carolina Ramblers got around, and their name did too. We’ll explore these name and personnel changes in detail, and conclude our look into the life of Posey Rorer when we get to Charlie Poole and the North Carolina Ramblers in song 20 “White House Blues”.

Connections

In this section, I examine the connections between this song and those that preceded it, but before we look at the bigger picture connections, I want to note how this song connects to “Ommie Wise”, the song which directly preceded it.

The theme of “one thing was promised, but a different thing was delivered” is at the heart of both songs. The title of each song contains a person’s name, and both songs continue the primary theme of “songs about historical events in chronological order by event”. Meanwhile, an outside connection between the songs is that in 1925, Kelley Harrell was backed by Henry Whitter on guitar and harmonica. Whitter was the musical partner of G.B. Grayson, who performed “Ommie Wise”.

Those are the connections between “My Name is John Johanna” and “Ommie Wise”, but what about the other songs on side B?

With our current song, we’ve got a humorous ditty about life on the job with a person’s name in the title, a band whose name indicates the state they’re from, and a fiddler who wasn’t credited on the record label.

For each song on Side B, some part of the previous statement holds true.

For “My Name is John Johanna”, the entire statement is true.

“My Name is John Johanna” ties the side together so neatly, that its placement cannot be a coincidence. It advances the larger theme of “historical events in chronological order”, a theme that began with “Peg and Awl” (1801-1804), then went to “Ommie Wise” (1807), before arriving in our current time frame which is roughly during the 1870’s The song then references several other smaller themes that have appeared on Side B.

Because of these intricate connections, I’m certain that this is not coincidence, but the work of Harry Smith, who decided to close the side with this song because it has so many tendrils connecting it to each of the preceding tunes.

For reference, here are the songs on Side B.

08 - King King Kitchie Kitchie Ki-Me-O by Chubby Parker and his Old Time Banjo

09 - Old Shoes and Leggins by Uncle Eck Dunford

10 - Willie Moore by Dick Burnett and Leonard Rutherford

11 - A Lazy Farmer Boy by Buster Carter and Preston Young*

12 - Peg and Awl by Carolina Tar Heels

13 - Ommie Wise by G.B. Grayson

14 - My Name is John Johanna by Kelley Harrell and the Virginia String Band

With the exception of Chubby Parker, all of the performers on side B played with string bands in the areas near the North Carolina / Virginia border. We also have the bands with state names in their names (Carolina Tar Heels, Virginia String Band, and I think we can safely add the Carolina Buddies to this list since they included Carter, Young, and Rorer). Several of these groups have direct connections to one another, thanks, in part, to Posey Rorer (who appears on two tracks) and Henry Whitter (who doesn’t appear at all), and then, of course, there's Clarence Ashley who played with the Carolina Tar Heels and appeared as a solo artist on side A.

This was our third consecutive song, (and fourth song on side B) that was recorded in a session overseen by Ralph Peer. It’s the third song on side B to discuss life on the job, the third comedic tune, and the third to have a person’s name in the title (although it could be the fourth if you count King Kong… which I don’t. Or do I?).

Other Interpretations

In this section, I share recordings recommended by Smith as well as other recordings of this song that I find interesting or noteworthy. Songs in the Discography below are recordings referenced by Harry Smith in the liner notes to the Anthology of American Folk Music. The Further Interpretations are versions of the song that I felt might be of interest.

Discography

Golden Melody Boys - Way Down in Arkansas - Released in 1928, this is another take on the tale, with entirely different music, and some significant lyrical differences. The order of events is a bit different, and the 7’2” Alan Catcher has grown even larger and changed his name. Here, he’s Joe Roberts, and stands 9 feet and 13 inches tall. Definitely an interesting alternative take on the song.

I.G. Greer - Sanford Barnes - (listed as AAFS 45 in Smith’s Discography) Unfortunately, I couldn’t find a recording of this online, but the transcription (by Charles Seeger) is below. Musically, it is the same as “My Name is John Johanna”. The performer, Isaac Garfield Greer, was born and raised in Watauga County, NC, in the Appalachian mountains and was known as a walking collection of folk songs. A professor of history and government at Appalachian State University, and song collector. By his own account, Greer made 452 public addresses in which he discussed and performed songs he’d collected, singing a capella or with an accompanist playing dulcimer.

The State of Arkansas

My name is Sanford Barney, and I came from Little Rock Town,

I’ve traveled this-a wide world over, I’ve traveled this~a wide world round.

I’ve had many ups and downs through life, better days I’ve saw,

But I never knew what misery was till I came to Arkansas.’Twas in the year of ’52 in the merry month of June,

I landed at Hot Springs one sultry afternoon.

There came a walking skeleton, then gave to me his paw,

Invited me to his hotel, ’twas the best in Arkansas.I followed my conductor unto his dwelling place.

It was starvation and poverty pictured on his face.

His bread it was com dodgers, and beef I could not chaw.

He charged me fifty cents a meal in the state of Arkansas.I started back next morning to catch the early train.

He said, “Young man, you better work for me. I have some land to drain.

I’ll give you fifty cents a day, your washing and all chaw.

You’ll feel quite like a different man when you leave old Arkansas.”I worked for the gentleman three weeks, Jess Harold was his name.

Six feet seven inches in his stocking length, and slim as any crane.

His hair hung down like ringlets beside his slackened jaw.

He was a photygraft of all the gents that ’uz raised in Arkansas.His bread it was com dodgers as hard as any rock.

It made my teeth begin to loosen, my knees begin to knock.

I got so thin on sage and sassafras tea I could hide behind a straw.

I’m sure I was quite like a different man when I left old Arkansas.I started back to Texas a quarter after five ;

Nothing was left but skin and bones, half dead and half alive.

I got me a bottle of whisky, my misery for to thaw;

Got drunk as old Abraham Linkern when I left old Arkansas.Farewell, farewell, Jess Harold, and likewise darling wife,

I know she never will forget me in the last days of her life.

She put her little hand in mine and tried to bite my jaw,

And said, “Mr. Barnes, remember me when you leave old Arkansas.”Farewell, farewell, swamp angels, to canebrake in the chills.

Fare thee well to sage and sassafras tea and corn-dodger pills.

If ever I see that land again, I’ll give to you my paw,

It will be through a telescope from here to Arkansas.

Further Interpretations

Charlie Parr - My Name is John Johanna - Performed live 2008-01-27 Ed's (No Name) Bar Winona, MN. If you don’t know Charlie Parr’s music, I do hope you enjoy this introduction. Charlie Parr is an outstanding singer/songwriter, guitarist, and banjoist, and he really gets these old songs. If you know Parr, then I suppose you probably already know all that stuff, and know what to expect.

Henry Thomas - Arkansas - We’re gonna talk a LOT about Henry Thomas in future installment of this series, but here’s a little taste of what his work was like. Unlike Charlie Parr’s solo banjo barnburner version above, this is not a cover of Harrell’s recording. It’s a medley, incorporating pieces of “Let Me Bring My Clothes Back Home”, “The State of Arkansas” (with a touch of “Rovin’ Gambler”), and “Travelin’ Man”.

Conclusion

“My Name is John Johanna” is a humorous song, but it’s a humorous song about a less-than-humorous topic. False advertising, deception, and starving, impoverished workers aren’t exactly fun topics to discuss, much less sing about. But if we can’t find some humor in the sorrows of life, we’ll surely be crushed by the weight of it all. At least John Johanna got out of the environment, and lived to make jokes about it. Not everyone was so fortunate.

As I’ve worked on this piece, I’ve thought a lot about the parallels between John Johanna’s experiences and those of Dust Bowl refugees who were lured to California by promises of jobs and good wages in the 1930’s, just a few years after this song was recorded. This song was prescient of many Okies’ fates, not because the song was composed by a gifted fortune teller, but because some human beings have a tendency to deceive and mistreat others for personal gain.

Sadly, it’s all too predictable. There are those who enjoy taking advantage of other folks for their own gain, and who savor each opportunity to make life even more difficult for people who are already in a bad spot. Even today, scores of people have fallen prey to schemes not unlike the one that lured John Johanna to Arkansas. They’ve left their homes for unknown lands on the promise of a better life, only to arrive and find they’ve not entered the promised land at all, just the land of broken promises.

Yeah, I know, I’m reading a lot into this funny old record, and that I ended on a pretty dark note, but that’s how it goes sometimes. With that, we’ve reached the end of the first album in Volume One - Ballads.

Thank you for being a part of this journey. I do hope you get something of value from these extensive explorations into the songs of Harry Smith’s Anthology. If you know someone who might appreciate what I’m doing, please share this article with them.

In the next installment, we’ve got song one from side C of Volume One, “Bandit Cole Younger” by Edward L. Crain. Spoiler alert, it continues our theme of songs with someone’s name in the title.

Lastly, although the editorializing and side commentary are the product of my mind, the actual facts presented here were collected by others and documented in various places. If you’d like to learn more about the topics in this article, all the sources I consulted are below.

Sources

"My Name Is John Johanna" - Kelley Harrell (Virginia String Band)

Where Dead Voices Gather at 78RPM

https://theanthologyofamericanfolkmusic.blogspot.com/2009/12/my-name-is-john-johanna-Kelley-harrell.html

State of Arkansaw, The - Encyclopedia of Arkansas

https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/the-state-of-arkansaw-song-5895/

Bluegrass Messengers - Isaac Garfield Greer’s Ballad Collection

http://www.bluegrassmessengers.com/isaac-garfield-greer%E2%80%99s-ballad-collection-.aspx

Kelly Harrell - Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kelly_Harrell

Crockett Kelley Harrell - World War I Draft Card

https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:7D73-336Z

"United States, World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918", FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:7D73-336Z : Tue Apr 29 06:24:55 UTC 2025), Entry for Kelley Crockett Harrell, from 1917 to 1918.

Crockett Kelley Harrell - Death Certificate

https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QVRZ-1V48

"Virginia, Death Certificates, 1912-1987", FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QVRZ-1V48 : Tue Mar 11 05:21:46 UTC 2025), Entry for Kelley Crocket Harrell and William Harrison Harrell, 25 Jul 1942.

Crockett Kelley Harrell - FamilySearch

https://www.familysearch.org/en/tree/person/about/LT63-QTP

Eugene Kelly Harrell

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/81645594/eugene-kelly-harrell

Byssinosis - Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Byssinosis

About Us - The Clubhouse Bed and Breakfast Resort

Archived on December 5, 2006.

https://web.archive.org/web/20061205114731/http://www.theclubhouseresort.com/AboutUs.htm

Fieldcrest Clubhouse History

https://fieldcrestclubhouse.com/fieldcrest-clubhouse-history/

Washington Mill in Fries, VA - May 1910

National Child Labor Committee collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

https://www.loc.gov/resource/nclc.01878/

Kelly Harrell - Discography of American Historical Recordings

https://adp.library.ucsb.edu/index.php/mastertalent/detail/108363/Harrell_Kelly

Posey Rorer - Discography of American Historical Recordings

https://adp.library.ucsb.edu/index.php/mastertalent/detail/108572/Rorer_Posey

Rambling Blues - The Life and Songs of Charlie Poole

Rorrer, Kinney

1982

McCain Printing Co. Inc, Danville, VA,

Old Irish folk music and songs : a collection of 842 Irish airs and songs, hitherto unpublished

Joyce, P. W. (Patrick Weston)

Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland

1909

https://archive.org/details/oldirishfolkmusi00royauoft/page/216/mode/2up

A Treasury of American Folklore - Stories, Ballads, and Traditions of the People

Edited by B.A. Botkin, 1944.

Crown Publishers, New York, NY

https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.29419/page/n346/mode/1up

Yet another great entry! I have always thought that Hills of Mexico (or Mexican Cowboy) was VERY similar to John Johanna in theme if not melody and lyric.

When I was in old Fort Worth in eighteen and eighty-three

Saw a Mexican Cowboy come steppin' up to me

Sayin', "How are you, young fella, yeah, would you like to go

For to spend another season with me in Mexico"

Oh, I had no employment, back to him did say

Said, "It's according to your wages, according to your pay"

Said, "I'll pay to you good wages, often to you home

If you spend another season with me in Mexico"

Spent his wages on that old steamboat and back to home did go

How the bells, they did ring, the whistles they did blow

How the bells, they did ring, the whistles they did blow

In the godforsaken forests on hills of Mexico

I love the tune John Johanna. One of my favorites off the Anthology. Really appreciate your Substack.

Farewell, you old swamp rabbits!

Kai