The Butcher's Boy by Buell Kazee [Anthology Revisited - Song 6]

TL;DR -- Themes of betrayal and heartbreak permeate a song with roots in multiple ballads. Is it "Butcher's Boy", "Railroad Boy", or both? Performer less elusive than those in previous installments.

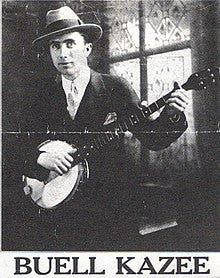

Welcome to the sixth installment of Anthology Revisited, a song-by-song journey through The Anthology of American Folk Music compiled by Harry Smith and released on Folkways Records in 1952. This time, we’ll examine Buell Kazee’s 1928 recording of “The Butcher's Boy”, a heartbreaking song about a girl done wrong that has roots in (at least) two older songs.

Just a heads up from the get go, the song we’re examining today involves suicide. If this theme troubles you and you’d prefer not to know the details, please note that all mentions of suicide in this article are limited to the introductory notes, lyrics, and the section covering “The Song”. Other sections of the article (“The “Performance”, “The Performers”, “Connections”, and “Other Interpretations”) contain no mention of the act, although any recordings of this song should be assumed to include such mentions.

Despite the grim topic (and the trigger warning in the previous paragraph), I have looked forward to writing this article ever since I was struck by the desire to write this series. To my ear, Buell Kazee is an exceptional vocalist, and a right solid banjo picker to boot. Consequently, I’ve been eager to examine and discuss his work in depth.

This is the first of two consecutive songs by Kazee to appear on the Anthology, and these recordings are the final two songs on Side One of Volume One of the Anthology, a somewhat notable point that we’ll discuss in the next installment. Buell Kazee will also appear when we get to song 58, “East Virginia” on Volume Three - Songs.

But before we get to know Buell Kazee and the story behind this grim tale, let’s check out Harry Smith’s headline…

FATHER FINDS DAUGHTER’S BODY WITH NOTE ATTACHED WHEN RAILROAD BOY MISTREATS HER

The headline is as straightforward as it gets. It may not be the most eloquent headline Harry ever penned, but it’s an apt description of the song. Some may wonder why the headline refers to a “Railroad Boy”, when the song is titled “The Butcher’s Boy”. This will be explained in due course, but first, here’s a quick rundown of the story told in the song

A young woman, visibly distressed, walks to her room without speaking. Her mother comes in to see what’s wrong, and the girl explains that she is heartbroken. She goes on to say that a railroad boy, who has been courting her, and with whom she’s desperately in love, is not being true to her. She explains that this railroad boy goes to a place in London Town and sits down. While he is there, a strange girl sits on the railroad boy’s knee. He speaks to the strange girl, and the words he says to this girl are words that he will not utter to the distressed young woman.

Although not explicitly stated in the text, the mother leaves her daughter alone with her heartbreak. Some time later, the young woman’s father comes home, and asks after his daughter due to her prior distress. He goes up to her bedroom to find that she has hanged herself. She’s left a note containing requests for what she’d like done with her body, and asks that a “snow-white dove” be over her coffin as a warning to the world that the woman buried here died for love.

I told y’all it was grim.

Here’s Kazee’s 1928 performance, give it a listen….

Lyrics

[Verse 1]

She went upstairs to make her bed

And not one word to her mother said

Her mother she went upstairs too

Says "Daughter, dear daughter, what troubles you?"[Verse 2]

"Oh Mother, oh Mother, I cannot tell

That railroad boy I love so well

He's courted me my life away

And now at home he will not stay"[Verse 3]

"There is a place in London town

Where that railroad boy goes and sits down

He takes that strange girl on his knee

And he tells to her what he won't tell me"[Verse 4]

Her father he came in from work

And said, "Where's daughter? She seems so hurt"

He went upstairs to give her hope

But found her hanging on a rope[Verse 5]

He took his knife and cut her down

And in her bosom these words he found:

"Go dig my grave both wide and deep

Place a marble slab at my head and feet

And over my coffin place a snow-white dove

To warn this world that I died for love"

The Song

Though the song contains a mere 22 lines of text, there’s an awful lot going on here. According to Smith’s liner notes, “The Butcher’s Boy” is an amalgamation of two songs, “The Cruel Father” and “There is an Alehouse in Yonder Town” (both of which are known by multiple alternative titles). This is accurate, but it’s not the whole story. There is a third song, “Sheffield Town”, from which “The Butcher’s Boy” also draws heavily, and a fourth song, “Sweet William”, which contributed to earlier versions of the ballad, but isn’t as evident in Kazee’s recording.

Sidebar: The Folk Process

Before getting into the song, I want to briefly touch on the concept of the folk process as it relates to music because “The Butcher’s Boy” is constructed out of parts of other songs.

While modern listeners may be surprised to find lines, stanzas, themes, characters, and concepts recycled and repurposed across seemingly unrelated songs, this borrowing and transforming of components is the core of the folk process. It’s something we’ll see much more of in the Anthology, so I figured a quick common sense history lesson about the folk process might be in order.

Before the printing press, songs were either shared orally or via handwritten texts. There were no means of mass production, thus, no way to ensure that the text remained the same across versions. Plus, performers would learn a song and add it to their repertoire. Over time, performers would make modifications as they saw fit, changing the text to reference a particular location, occupation, or scenario so that the song would resonate with the audience. These modifications can include importing lines, stanzas, characters, or concepts from other songs. This process has been repeated by countless performers over generations in locations on both sides of the Atlantic, and the results are all a part of this wild tapestry of songs in the folk canon.

Post-Sidebar Sidebar: Broadsides

Songs were passed along either orally or via handwritten text before the printing press came along. Once the printing press revolutionized things, broadsides were used as one of the first forms of mass communication. Printed on one side of a sheet oversize paper (hence the name) and posted in public areas, broadsides were used to convey news and commentary, which ofttimes came in the form of songs. Broadsides began shortly after mass printing came into being, and continued into the early 20th century.

The Building Blocks of the Butcher’s Boy

In a supplemental article published with this piece titled “Whence the Butcher’s Boy?”, I examine multiple versions of the source songs referenced by Smith, as well as “Sheffield Park”, a primary source for this song that was not mentioned by Smith, to show where the parts of “The Butcher’s Boy” originated, and briefly introduce “Sweet William”, which contribute to the broadside text.

That analysis was part of this essay, but because multiple texts of multiple songs are examined, it runs long. Instead of including all those texts here, I created the supplemental article for folks who want to see how these source songs evolved, and what they contribute to “The Butcher’s Boy”.

The key takeaways from the supplemental article “Whence the Butcher’s Boy?” are:

“The Cruel Father” contributes the core theme; a young woman who is willing to die for love. While the young woman dies in one version, it is not by her own hand.

“There Is an Alehouse in Yonder Town” provides the young lady’s mournful complaint about the young man’s habit of sitting elsewhere with a different girl on his knee.

“Sheffield Park” gives us the household activities that appear in “The Butcher’s Boy” such as the daughter seeming distressed, going upstairs, being asked what is wrong, and explaining the situation.

“Sweet William (aka, “A Sailor’s Life”) shares lines with the 1890’s broadside “The Butcher Boy”, but not with Buell Kazee’s 1928 recording.

All these pieces first came together in the broadside “The Butcher Boy”, which appeared in the 1890’s. This version of “The Butcher Boy” (below) contains all of the components that appear in Buell Kazee’s 1928 recording of the song, as well as additional material (mostly taken from “Sheffield Park” and “Sweet William”) that Kazee omits.

Below is the text of the song as printed on the broadside. Text in bold italics (or some minor variation thereof) appears in Kazee’s version.

The Butcher Boy

In Jersey City, where I did dwell,

A butcher-boy I loved so well,

He courted me my heart away,

And now with me he will not stay.

There is an inn in the same town,

Where my love goes and sits him down;

He takes a strange girl on his knee,

And tells to her what he don't tell me.It's a grief for me; I'll tell you why:

Because she has more gold than I;

But her gold will melt, and her silver fly;

In time of need, she'll be poor as I.

I go up-stairs to make my bed,

But nothing to my mother said;

My mother comes up-stairs, to me

Saying, "What's the matter, my daughter dear!""Oh! mother, mother! you do not know

What grief, and pain, and sorrow, woe-

Go get a chair to sit me down,

And a pen and ink to write it down."

On every line she dropped a tear,

While calling home her Willie dear;

And when her father he came home,

He said, "Where is my daughter gone?"He went up-stairs, the door he broke-

He found her hanging upon a rope-

He took his knife and he cut her down,

And in her breast those lines were found:

"Oh! what a silly maid am I! To hang myself for a butcher-boy!

Go dig my grave, both long and deep;

Place a marble-stone at my head and feet,

And on my breast a turtle dove,

To show the world I died for love!"

Buell Kazee’s 1928 recording of “The Butcher’s Boy” is clearly derived from the text published in the 1890’s. Kazee’s version doesn’t add any additional information, although it omits some lines and rearranges the text of the broadside.

The Performance

When discussing “The House Carpenter”, the third song in the collection, I mentioned how Clarence Ashley’s vocals and banjo worked together to give the song a spooky, mountain vibe. Here, Kazee’s vocal and clawhammer banjo playing combine to create a similar “high lonesome” feel, but Kazee’s performance is more than spooky, it’s grim and haunting.

When delivering the song, Kazee, like Ashely, assumes the role of detached reporter of events. In spite of Kazee’s flawless diction and detached delivery, there remains a degree of mournfulness in his voice. Once the final verse is complete, Kazee’s banjo continues for a moment, and when the sound of the last note bounces from the banjo, the song ends with a touch of room noise from the studio before the track finishes.

I like it when recordings have little moments of studio silence, because in these moments, listeners can hear the room’s contribution to the overall sound. While my hearing loss makes the sound of the room all but imperceptible, I’ve listened to these recordings enough to still know it’s there.

Why does Buell Kazee sing “railroad boy”?

In several previous articles, facts about performers and performances have been incredibly scarce, but this time,we’ve got a wealth of information. There’s SO much information available, that the performer himself can explain why he’s singing about a “railroad boy” in a song called “The Butcher’s Boy”.

In the first 90 seconds of the recording below, Kazee explains the discrepancy between the song’s title and the words he sang in 1928. Afterwards, he sings “The Butcher’s Boy” (really).

Transcription (slightly edited for clarity)

“The Butcher's Boy”, of course, is the original ballad in England, and that's the title that is known among people who deal in folk songs a good deal. But, in this country, especially in the Kentucky mountains, it became “The Railroad Boy”. … When the railroads began to go up the Sandy Valley and the East Virginia border and all, that became quite a romantic thing to the Mountaineers mind, you know. And, They got the singing Railroad [Boy] for instance in there…. In that song, you have, “there's a place in London Town where the butcher's boy goes and sits down”. Well, they're saying it. “There is a place in Lebanontown where the railroad boy goes and sits down”. … Lebanon is down here in Kentucky and happens to be railroad junction. Place where two [rail]roads come together…. And that probably was known by somebody who sang the song and he got it in there. Well, it had such an influence on me. I sang it all my life as “railroad boy”, and I've heard my older sister sing that way. When I got to New York to record it, I knew we were going to record ”The Butcher's Boy” and we wanted to record ”The Butcher's Boy” because that was the way it was known in England. … But in spite of all I can do, all I could do, even though we call it ”The Butcher's Boy”, when I got to the verse where it was supposed to be, I called “the railroad boy”

The recording above is from the 1958 album Buell Kazee Sings and Plays, and as you can hear, he got the words right, and the title and lyrics of “The Butcher’s Boy” actually match up.

The story behind this recording is that in 1957, when the folk revival was underway (due in no small part to the Anthology of American Folk Music), a Ph.D student named Gene Bluestein from the University of Minnesota sought out Kazee in Lexington, Kentucky. He found Kazee and recorded him discussing and performing songs. Bluestein’s recording was the first commercial release of Kazee’s performances in almost 30 years.

It should be noted that Kazee was not fond of this recording, as he felt it was too casual. As far back as 1925, Kazee would perform songs in concert and deliver brief lectures on the songs and their origins. These performances were well-rehearsed affairs, and it seems that Kazee had misgivings about the recording because he would have preferred to do a more thorough and formal presentation.

The Performer

Buell Kazee appears thrice on the Anthology and, as evidenced in the previous segment, he was among the performers who enjoyed a career resurgence during the folk revival. Unlike many of the other performers appearing on the Anthology, a wealth of biographical information is available about Buell Kazee. Since I have three articles to write about his work, I’ve decided to split Kazee’s biographical information into three parts. The first, presented below, covers his early life up until just before his first recording session. The second part, covering Kazee’s recording career and life between 1929 and 1958, will appear in the next installment of Anthology Revisited (Song 7, “The Wagoner’s Lad”). The final installment, covering Kazee’s life during and after the Folk Revival, will appear when we get to song 58, “East Virginia”.

Buell Kazee was born on August 29, 1900 in a two-room log cabin near the head of a creek called Burton Fork in rural Magoffin County, Kentucky, a sparsely populated area of the Cumberland Mountains. In fact, the only incorporated town in Magoffin County is the county seat of Salyersville, which is about four miles from Burton Fork.

To put this into numbers, when Kazee was born in 1900 the population of Magoffin County was 12,000 people. In the 2020 census, 11,637 people lived in Magoffin County. In 1900, Salyersville had a population of 265. In 2020, it had a population of 1,591. This is rural living! The image below provides a general idea of where Burton Fork is located. You can explore the area further on Google Maps.

In a July 10, 1974 interview with Loyal Jones (part one, part two), Kazee was asked when he began playing banjo, and he replied that he was five years old, and shared the following story about how he acquired his first banjo. (Transcript edited for clarity)

“I went over to aunt Sade’s one night, and they had one [a banjo] over there they had worn out, they thought. There was a hole in the hide or the head, where your fingers rest in order to pick. It was all homemade; a walnut neck. The boys over there were artisans… good carpenters,and they had made a banjo. I cried for that one and they gave it to me. I carried it home under dad’s old coat to keep it out of the rain. … Sherrod Connoley, Sherman, he was the fella who’s always catching animals and skinning them, y’know, and tanning hides. So, he caught a cat, tanned that hide, and put it on my banjo. … He tacked it on with carpet tacks, and I had my banjo. … It had no frets.”

The Baptist History Homepage article on Kazee contains a slightly more detailed description of Kazee’s first banjo.

“The neck of the instrument was a whittled piece of walnut, the hoop was made from split white oak, and a home-tanned cat skin hide was stretched over the hoop and fastened with carpet tacks”

Kazee learned to play in the clawhammer style by watching other banjo players in the area. He grew up playing the songs he learned others in the area, and developed a keen appreciation for the old traditional ballads from his mother, who sang the songs at home.

Kazee graduated high school and attended college at Georgetown College (a Baptist college in Georgetown, Kentucky) where he studied English, Latin, and Greek. While in college, he also studied music and singing, and began transcribing some of the folk songs that he learned in his younger years.

On April 9, 1925, shortly before he graduated from Georgetown College, Buell and other members of the Georgetown Glee Club performed in a show that was broadcast over WLW radio of Cincinnati, Ohio. In this performance, Kazee sang “My Little Ireland Home”.

A second performance by the group aired on Louisville, KY station WHAS on April 23, 1925, during which Kazee sang “Lassie O’Mine”. Kazee’s performances were getting some local attention, as several articles appeared in local newspapers. (Further details can be found on the outstanding entry on Kazee at hillbilly-music.com)

Kazee completed his degree at Georgetown College in 1925. On August 11th of 1925, Kazee gave a concert at the University of Kentucky in Louisville, KY, where he performed folk songs and spoke on the history of the songs. He played banjo and was accompanied by Mrs. Eugene Bradley on piano and Miss Amy Dawes on violin. During the performance, Kazee is said to have focused on the more comical songs of the region and included a mix of ballads, folk songs, and African-American spirituals. Kazee is said to have referred to African-American performers as “soul singers” because of the range of emotions they could express in song.

Kazee worked briefly in Oklahoma before returning to Kentucky, where an instructor from Georgetown informed Kazee that the Ashland Conservatory of Music was seeking a male vocal teacher. He worked there for a period, before moving on to teach vocal lessons from his own studio, and pursue his other calling, preaching.

In 1927, “hillbilly” music was gaining nationwide popularity, and a local music store operator in Ashland, who was also a scout for Brunswick Records, arranged for Kazee to go to New York for his first recording sessions.

Information about Kazee’s recording career and his activity between 1929 and 1958 will be in the next installment of Anthology Revisited, but I cannot end this section without showing you a little hint of what’s to come.

Y’see, Buell Kazee is the first performer on The Anthology of American Folk Music of whom we have video footage. And I’m not talking about just a couple of seconds either. We’ve got a surprising amount of video featuring Buell Kazee. This footage was recorded during and after the folk revival, and I’ll share much more in future articles about Kazee, but I couldn’t end this section about “The Performer” without hipping you to these facts. So, here’s a little taste of what’s to come. Here’s Buell Kazee performing “In The Pines” during the September 21, 1972 convocation at Berea College. Please note, this song that has absolutely nothing to do with “The Butcher’s Boy”. I’m just sharing it because footage of the performer exists.

Connections

As previously mentioned, “The Butcher’s Boy” is the first track on the Anthology that isn’t based on a Child ballad. Although the song was not cataloged by Francis James Child, it still has roots in the British Isles, as do all the other songs we’ve discussed so far.

Like the song preceding it, “The Butcher’s Boy” is an amalgamation (or what modern folks might call a mashup) of songs. The previous song, “Old Lady and the Devil”, opened with a quatrain borrowed from a nursery rhyme before getting into the ballad cataloged by Child as “The Farmer’s Curst Wife”. Similarly, “The Butcher’s Boy” is constructed from three sources, “The Cruel Father”, “There is an Alehouse in Yonder Town”, and “Sheffield Park”.

Betrayal is a theme that has appeared in some form or another in every song we’ve discussed so far, and here, the “railroad boy” betrays the young woman with his actions in London Town. Relationship woes, continue to be a theme, as they have been in each song since song 3, “The House Carpenter”.

While this isn’t a murder ballad, someone is slain for the fifth time in six songs. In fact, the only song that hasn’t included a death is Coley Jones’ “Drunkard’s Special”, although an argument could be made that the drunkard’s marriage seems to be nearing death.

This is the second banjo song in the Anthology, and the first is song 3, “The House Carpenter”.

Other Interpretations

Here are some other recordings of The Butcher’s Boy and the Railroad Boy. As always, we’ll start with the ones recommended by Harry Smith in the discography and follow it up with further recordings.

Discography

Henry Whitter - The Butcher Boy - This 1925 recording of “The Butcher Boy” has its roots in the same 1890 broadside as Kazee’s version. However, Whitter uses some stanzas from the 1890 text that don’t appear in Kazee’s recording. While Whitter’s version ends the same way as Kazee’s, the rest of the song almost sounds like a different story altogether.

Blue Sky Boys - The Butcher’s Boy - This recording was made in a February 5, 1940 session in Atlanta, Georgia for Victor (which was actually already part of RCA at this time, but there label wasn’t referred to as RCA Victor until later in the 1940’s). The lyrics here are almost identical to those Whitter used in his recording.

The sound quality of this recording is an immeasurable improvement over Whitter’s recording, and is a testament to the dramatic evolution of recording and record pressing techniques and technologies in the 15 years between 1925 and 1940.

Kelly Harrell - Butcher’s Boy - This 1925 recording of “Butcher’s Boy” was among the first recordings made by Harrell. This version is similar to Whitter’s version, but not identical.

Further Interpretations

Joan Baez - Railroad Boy (1961) - This recording comes from Joan Baez 1961 sophomore album, appropriately titled “Vol. 2”, and is taken word for word from Kazee’s 1928 recording.

This performance (and the next one) clearly show just how much the Anthology influenced the performers of the folk revival. While other versions of “The Butcher’s Boy” / “Railroad Boy” surely existed, Kazee’s recording was obviously the template for these performances, thanks to the work of one Harry Smith.

Bob Dylan - Railroad Boy (1961) - Like Baez’s performance above, this performance by 19 year old Bob Dylan stays within the lines of Kazee’s 1928 recording, and doesn’t bother with any of those other verses that appear elsewhere.

Bob Dylan and Joan Baez - Railroad Boy (live Fort Collins, TX 1976) - Since I shared Baez and Dylan performing “Railroad Boy” independently, I figured it would be fun to share a recording of the pair performing the song together, 15 years after the previous versions were recorded. I apologize for including a track that is part of a longer video, but other recordings of this performance on YouTube are either of lower quality or have distracting visuals. Hopefully this is cued up to the right spot. You may have to wait a few seconds, but it’s worth it.

Gov’t Mule - Railroad Boy (Live - Beacon Theater - New York City, NY - 12/30/2024) - American rock band Gov’t Mule recorded Railroad Boy for their 2009 album By a Thread. The studio recording is quite nice, but there are some performers whose best work is done on stage. Warren Haynes (guitarist and vocalist) is one such performer, and if I’m including his work, I prefer to share his live performances. This is an audience-shot video, so it’s not a 100% crispy clean experience, but neither is Henry Whitter’s version of “Butcher Boy”, so I think you can handle it.

Conclusion

Well, this has been a fun little trip, hasn’t it? I hope you enjoyed it, and I hope you were as delighted to see an actual performance by someone who appeared on the Anthology. (But if you think that’s something, just wait til next week!)

If you’re up for more deep digging, check out the “Whence the Butcher’s Boy?” where I break down multiple versions of the source songs for “The Butcher’s Boy”.

Next week’s edition of “Anthology Revisited” features Buell Kazee’s performance of “The Wagoner’s Lad”, more information about Kazee’s professional recording career than you probably ever wanted, and our trademark wit and sense of adventure. :)

As always, I could not have done this work alone. I stand on the shoulders of giants, building on the foundation they laid. My ongoing gratitude goes to all the dedicated fans, researchers, and writers who’ve done their homework to make all this material available.

If you want to learn more, the sources I consulted when writing this article (and the supplemental article “Whence the Butcher’s Boy?”) are below, and trust me, there’s a lot more to explore out there on Buell Kazee.

Sources

Buell Kazee - Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Buell_Kazee

Where Dead Voices Gather: Life at 78 RPM: "The Butcher's Boy (The Railroad Boy)" - Buell Kazee

https://theanthologyofamericanfolkmusic.blogspot.com/2009/11/butchers-boy-railroad-boy-buell-kazee.html

Buell Kazee, reissued | Root Hog Or Die

https://roothogordie.wordpress.com/2007/06/16/buell-kazee-reissued/

6 “The Butcher’s Boy” by Buell Kazee | My Old Weird America

https://oldweirdamerica.wordpress.com/2008/12/17/6-the-butchers-boy-by-buell-kazee/

Broadside (printing) - Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Broadside_(printing)

The Cruel Father / Her Servant Man / The Iron Door (Roud 539)

https://mainlynorfolk.info/peter.bellamy/songs/thecruelfather.html

"The Cruel Father, or, The affectionate Lover," and "The Boughleen Dhoun", undated

University of Notre Dame Rare Books & Special Collections

Irish Broadside Ballads (BPP_1001)

Series 1: Broadsides, chiefly printed by P. Brereton of Dublin, 1860-1876

https://archivesspace.library.nd.edu/repositories/3/archival_objects/1055246

Yates, M. (1980). The Cruel Father and Constant Lover - A Broadside Ballad in Tradition. MUSICultures, 8. Retrieved from https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/MC/article/view/21836

Evidence of early 1800’s broadside containing text of “The Cruel Father and Constant Lover” (The actual document is in a rare books collection that is inaccessible to this researcher) -

The cruel father, and constant lover.. - Pitts, John, 1765-1844 - London : Printed and sold by J Pitts 14 Great st andrew Street seven Dials, between 1802 and 1819

https://natlib-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/primo-explore/fulldisplay?vid=NLNZ&docid=NLNZ_ALMA71218652630002836&context=L&search_scope=NLNZ

Folk Music Index - Bum to Bz

https://www.ibiblio.org/keefer/b17.htm#Butbo

The Butcher's Boy (folk song) - Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Butcher%27s_Boy_(folk_song)

In Sheffield Park (Roud 860)

https://mainlynorfolk.info/eliza.carthy/songs/sheffieldpark.html

Sheffield Park - Yorkshire Garland Group

https://www.yorkshirefolksong.net/song.cfm?songID=39

A Brisk Young Sailor Courted Me

Folk Songs of Sussex - George Butterworth - Published 1913

https://archive.org/details/folksongsfromsus00butt/page/14/mode/2up

The Butcher’s Boy - Journal of American folklore v.35 1922

American Folklore Society. Journal of American Folklore. Washington [etc.]: American Folklore Society,

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015034746373&seq=382

Traditional Tunes - Kidson, Frank - 1891 (pp 44-46)

https://archive.org/details/imslp-tunes-kidson-frank/page/n47/mode/2up

Buell Kazee Discography by Norm Cohen

Archived on July 25, 2008 from http://www.appalshop.org/archive/kazee/Updated-Discography-by-Norm-Cohen.pdf

Retrieved from Internet Archive https://web.archive.org/web/20080725072852/http://www.appalshop.org/archive/kazee/Updated-Discography-by-Norm-Cohen.pdf on April 21, 2025.

Rev. Buell Hilton Kazee (Familysearch.org)

https://www.familysearch.org/en/tree/person/about/KD79-6KB

Rev. Buell Hilton Kazee (Findagrave.com)

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/157669223/buell_hilton-kazee

Baptist History Homepage - Buell Kazee Biography

Archived on October 28, 2009 from http://www.geocities.com/baptist_documents/kazee.buell.bio.html and retrieved from Internet Archive https://web.archive.org/web/20091028083941/http://www.geocities.com/baptist_documents/kazee.buell.bio.html on April 21, 2025

Magoffin County, Kentucky - Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Magoffin_County,_Kentucky

Salyersville, Kentucky - Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Salyersville,_Kentucky

Buell Kazee entry at Hillbilly-music.com, from which much early biographical information was drawn, includes references to newspaper articles from throughout Kazee’s life.

https://www.hillbilly-music.com/artists/story/index.php?id=10391

Evening Star (Washington, DC) August 4, 1927 - Page 16

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1927-08-04/ed-1/seq-16/

Buell Kazee - Discography of American Historical Recordings

https://adp.library.ucsb.edu/index.php/mastertalent/detail/106315/Kazee_Buell

Recording of Buell Kazee being interviewed by Loyal Jones on July 10, 1974.

Berea College Special Collections and Archives - Southern Appalachian Collections - Buell Kazee Collection

Part 1 - kazee-interview-1974-07-14-AC-CT-054-018_a

https://berea.access.preservica.com/uncategorized/IO_064ea9c2-6755-49d8-83d2-e811a08af8c8/

Part 2 - kazee-interview-1974-07-14-AC-CT-054-018_b

https://berea.access.preservica.com/uncategorized/IO_861b91c5-ef81-4ec0-be51-7518bf3da331/