Charles Giteau by Kelly Harrell and the Virginia String Band [Anthology Revisited - Song 16]

TL;DR -- Mentally ill man murders President Garfield, writes song (not this one), meets hangman. Great Depression wrecks recording careers. New information unearthed about two performers.

Welcome to the sixteenth edition of Anthology Revisited, a song-by-song examination of the Anthology of American Folk Music, compiled by Harry Smith and released by Folkways Records in 1952, and reissued in 1997 by Smithsonian Folkways.

In this installment, we’ve got “Charles Giteau” [sic], a song about the 1881 murder of president James A. Garfield, recorded for Victor Records in Camden, New Jersey on March 23, 1927 by Kelley Harrell and the Virginia String Band.

NOTE ONE: While the record labels show his name as “Kelly Harrell”, his name is spelled “Kelley” on official documents and his tombstone, so that’s what I’m sticking with.

NOTE TWO: Our title character’s last name is misspelled on the record label. Throughout this article, when I refer to this recording, I’ll use “Giteau”, the inaccurate spelling from the record label, and when referring to the person, I’ll use the proper spelling, “Guiteau”.

We’re in our fifth song in Harry Smith’s musical timeline, and today’s track takes us back to the early 1880’s for a song named for its subject, Charles Guiteau, the man who assassinated James A. Garfield, the 20th President of the United States. Although, an argument could be made that Garfield was actually killed by medical ineptitude, but we’ll get to that in a bit.

This will be an especially lengthy article covering a lot of territory. We begin with a close look at “Charles Giteau” (the song) and Charles Guiteau (the man), talk about the highs and lows of this recording, finish our two-part discussion of Kelley Harrell’s life and career, then reveal what findings about the two members of the Virginia String Band whose lives went unmentioned in the article on “My Name is John Johanna”. Due to the wealth of content in this edition, the typically rambling introductory remarks are being cut short. Without further ado, here’s Harry Smith’s headline for this song.

ASSASSIN OF PRESIDENT GARFIELD RECALLS EXPLOIT IN SCAFFOLD PERORATION.

Smith’s headlines are designed to give us an overview of the events in the song, and in this way, the headline is spot on accurate. In this song, we are with Guiteau on the final day of his life. He explains his predicament, and walks us through the events that led to this moment that finds him upon a scaffold, singing a song, with a noose around his neck.

We’ll unravel Smith’s other statements when we discuss the song in a few moments. But first, let’s take a listen to “Charles Giteau” as performed by Kelley Harrell and the Virginia String Band on March 23, 1927 in Camden, New Jersey.

Lyrics

Come all you tender Christians

Wherever you may be

And likewise pay attention

To these few lines from me.

I was down at the depot

To make my getaway

And Providence being against me,

It proved to be too late.I tried to play off insane

But found it would not do;

The people all against me,

It proved to make no show.

Judge Cox he passed the sentence,

The clerk he wrote it down,

On the thirtieth day of June

To die I was condemned.Chorus:

My name is Charles Giteau,

My name I'll never deny,

To leave my aged parents

To sorrow and to die.

But little did I think

While in my youthful bloom

I'd be carried to the scaffold

To meet my fatal doom.My sister came in prison

To bid her last farewell.

She threw her arms around me;

She wept most bitterly.

She said, "My loving brother,

Today you must die

For the murder of James A. Garfield

Upon the scaffold high."REPEAT CHORUS

And now I mount the scaffold

To bid you all adieu,

The hangman now is waiting,

It's a quarter after two.

The black cap is o'er my face,

No longer can I see,

But when I'm dead and buried,

Dear Lord remember meREPEAT CHORUS

The Song

As mentioned in the intro, the song is Guiteau’s story as told from the scaffold, but that only becomes clear near the end of the song. Before we dig into exactly what happened, let’s see what facts the song gives us, then we’ll see what Harry Smith and other sources have to say.

The Events of the Song

The song begins with a verse twice as long as the other verses in the song. The first half offers a brief introduction, asking all tender Christians to pay attention, then immediately gets into the action at the depot where our narrator was trying to make a getaway. The word “getaway” suggests that some criminal activity was afoot, but exactly what or whom our narrator is fleeing is not yet made clear. We’re know only that Providence was not on his side.

The second half of the verse clarifies matters a bit, explaining that our narrator was captured while trying to escape the long arm of the law. At his trial, our narrator tried to plead insanity, but his plea was rejected and he was condemned to death by Judge Cox. At this point, we know neither our narrator’s identity, nor the crime for which he has been sentenced to die.

When the chorus comes in, our narrator is revealed to be Charles Guiteau. We are reminded that his is soon to be executed, but we’ve still no indication as to why he has been condemned to die.

In the second verse, the answers trickle in. Guiteau’s sister pays him a visit in prison to say goodbye before he is hanged for the murder of James A. Garfield. (The song assumes listeners are aware that James A. Garfield was the 20th president of the United States as this is never explicitly stated.)

The chorus is repeated, and after a very cool little guitar break, we’re in the final verse, standing on the scaffold with Guiteau in his final moments. The mask is over the condemned man’s face, and the hangman is on standby, waiting only for the song to end before setting to his task. Guiteau asks the Lord to remember him, the chorus comes through once more, and the song ends.

Harry Smith’s Notes on the Song

I’m going to refer back to Harry Smith’s original liner notes to set up the rest of this section, and then we’ll look at what really happened. We’ve already discussed the headline, and now I want to focus on Smith’s blurb about the song. After the headline, Smith’s introductory notes include the following statement.

James A. Garfield, 20th President of the United States was shot on July 2, 1881 in a Washington railway station by a disappointed office seeker Charles J. Guiteau.

This is a statement of fact. Every word of that sentence is accurate, and I’ll expand upon it momentarily. The next sentence states:

It may be an adaptation of an earlier song “My Name is John T. Williams”.

This may or may not be true. I’ve yet to locate a text for “My Name is John T. Williams”. If I locate the text of the song, I will add it to this article, and do an appropriate comparison. As of this writing, the text of “My Name is John T. Williams” remains elusive.

The final sentence of Smith’s notes states.

The song is also alleged to be the work of Guiteau himself who sang it to visitors in his death cell.

That a president’s assassin would write a song about himself and sing it to visitors is a pretty wild notion. Were it true, it would be a truly fascinating, albeit morbid, bit of information. Sadly, it’s not true, and if you think about the lyrical content of the song, you’d know Guiteau himself wouldn’t sing it because it contains specific details about the day of Guiteau’s execution, something about which he wouldn’t have such foreknowledge.

Having established that this song was not composed by Guiteau, and that he didn’t sing it to visitors, it’s important to note that Guiteau did write a poem that he sang/read on the scaffold at his execution, but it wasn’t this song. We’ll get to that in a bit, but now that we’ve worked through Harry Smith’s statements, we need to talk about Charles Guiteau.

Part 1 - His Name was Charles Guiteau

Throughout this series, our discussions of real people have been limited to the sections on the Performers. While the past few installments have included sections about real events. discussions to the real people involved have been surface level affairs. All that is about to change. To understand why Guiteau killed President Garfield, we need to get to know Guiteau and understand the forces that drove him to act.

When I write about real people, I try to be compassionate and see the world through their eyes. I write with empathy, trying to treat my subjects with the same kindness I would want should someone posthumously catalog my own affairs. I’m not here to pass judgment. I’m just here to tell a story. In the case of Charles Guiteau, withholding judgment is difficult. He was a sad, sick, and pitiable character, and truly adopting his point of view would require severing ties with reality. I won’t go that far, but I have tried to create a fair and generous accounting.

Charles Guiteau had a difficult life. He was born in 1841 in Freeport, Illinois, and was the fourth of six children. His mother suffered from some form of mental illness, described vaguely as psychosis, but there is no formal diagnosis that I could find. When Guiteau was seven years old, his mother died, and for a while, he was raised mostly by his older sister, Franky. When Charles was twelve years old, his father remarried and his new stepmother assumed some responsibility for his care. Things were never easy for Charles. From youth, he had speech difficulties, and was afflicted with what we in modern times would call ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder). Sadly, that’s just the tip of the iceberg.

In his late teens, Guiteau seemed to be an enterprising young man. He was taking classes to make himself eligible to attend the University of Michigan. But before he could finish these classes, Guiteau became distracted by letters from his father praising the Oneida Community in New York. Guiteau soon quit his studies to join the religious sect. Once at Oneida, Guiteau became fascinated by the teaching of the group’s leader, John Humphrey Noyes, and stayed with the group for five years.

If you’re not familiar with the Oneida community, I’ll give you a rough sketch and trust you to seek out more information if you want to know more. Oneida was started by Noyes as a perfectionist religious community. The sect believed that Christ returned in AD 70, and since Christ had already returned, they were obliged to make the Christ’s millennial kingdom a reality on earth. The Oneidans practiced communalism (in that all property belonged to all members of the sect), complex marriage (everyone was married to everyone else), and “free love” (a term credited to Noyes to describe guilt-free, relationship-free sexual activity between consenting adults within the community). They also practiced “male continence”, whereby men were discouraged from ejaculating inside of women, which helped to keep birth rates lower in the community. The free love aspect attracted Guiteau, but it rarely, if ever, seemed to work out in his favor. Guiteau was regularly left out of the excitement, and others in the Oneida community are said to have dismissed him with a cruel play on his last name, “Charles Gitout”.

So, at this point, Guiteau is in his early 20’s. He is surrounded by a bunch of other people who are regularly engaging in sexual activities with one another in varying configurations. As most young men in their early 20’s would do, Guiteau saw this going on and wanted to get in on the action, but was regularly and repeatedly rejected. This same guy lost his (psychotic) mother when he was a child. Difficulties establishing and maintaining relationships with other people will come up again.

Guiteau left Oneida for Hoboken, NJ where he tried to start a newspaper called The Daily Theocrat. This went nowhere, and Guiteau went back to Oneida. After a year, he left Oneida again, and eventually filed lawsuits accusing Noyes of not paying him for his work. Guiteau’s own father wrote a letter to the court in defense of Noyes, in which he suggested that his son Charles was irresponsible and insane.

Guiteau wound up in Chicago, where he passed the bar exam and worked as a debt collection attorney. Guiteau seems to have had a little trouble with honesty and didn’t always give his clients the money he collected for them. While in Chicago, he married, and proved to be a tyrannical and abusive husband who would beat his wife and lock her in the closet for hours on end.

In 1872, Guiteau and his wife moved to New York City, where his interest in politics grew. He threw his support behind the Democratic presidential nominee, Horace Greeley. Guiteau even gave a speech promoting the candidate. During the campaign, Guiteau somehow convinced himself that Greeley would name him ambassador to Chile if he won the election. Greeley lost to Ulysses Grant, and Guiteau’s delusion dream was shattered.

In 1874, Guiteau’s wife asked for a divorce. Guiteau hired and had sex with a prostitute so that his wife could request a divorce on the grounds of adultery and the prostitute testify to his infidelity. The following year, Guiteau published “The Truth”, a religious book constructed of mostly text plagiarized from Noyes, and began to live as an itinerant preacher. Throughout this time, Guiteau’s father was becoming convinced that his son was possessed by Satan.

In 1880, with a head still full of religious zeal leading him to believe he was sent by God, Guiteau became involved in presidential politics again. Unlike modern American political conventions where the outcome is predetermined by the party well in advance, delegates entered the 1880 Republican National Convention uncertain of whom their party’s Presidential nominee would be.

Entering the convention, Guiteau was aligned with the Stalwart wing of the Republican party, which was initially in support of Ulysses Grant. After multiple rounds of voting, the delegates struggled to find a candidate whom a majority of party factions would endorse. When James A. Garfield emerged as a dark horse candidate for the nomination on the 34th ballot, Guiteau edited the text of a speech he’d written in support of Grant, scratching out the name “Grant” and adding “Garfield” in its place. Garfield delivered Guiteau’s speech, (possibly on two separate occasions), and hard copies of the text were available at the convention. After Garfield won the nomination on the 36th ballot, Guiteau concluded that this speech was the key element that turned the convention in Garfield’s favor.

After Garfield’s nomination was secured, Guiteau, fully convinced he was on a divine mission, became a fixture at the New York Republican headquarters where he persistently lobbied for speaking opportunities. His efforts were mostly ignored, but the party gave him one speaking engagement before a small audience of Black voters in New York.

After Garfield won the presidential election, Guiteau was convinced that he held an outsize role in shaping the outcome. He wrote to President-Elect Garfield on New Year’s Eve 1880, to wish the Garfield family a happy new year and request an appointment to be a US diplomat to a foreign nation. This was but the first such request from Guiteau. In the months that followed, he relentlessly peppered Garfield and members of his administration with requests for consulship, both via mail and in person.

Secretary of State James Blaine received an especially high volume of correspondence from Guiteau, demanding a consulship. He first requested a consulship in Vienna, and later in Paris. In a face-to-face confrontation at the Department of State on May 14, 1881, four days after having received yet another correspondence from Guiteau regarding an appointment to consulship in Paris, Blaine told Guiteau to his face, and in no uncertain terms that he would not receive the appointment, and to never speak to him of the Paris consulship again.

Prior to this moment, Guiteau had been in a downward spiral. He was depressed, broke, bouncing from boarding house to boarding house (where he regularly skipped out on rent), and seething over being denied the post he thought he so rightly deserved. Blaine’s direct rejection pushed Guiteau over the edge. After the incident Guiteau seems to have stopped contacting the Garfield administration. Instead, he set his mind toward an evil deed that he’d convinced himself to be the Will of God. On June 15, with evil notions in his mind and fifteen borrowed dollars in his pocket, Charles Giteau purchased a .44 British Bulldog revolver at a Washington DC store called O’Meara’s, then spent a couple of weeks learning how to hit a target with a pistol.

On July 2, 1881, Charles Guiteau waited in the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad Station, where the President was scheduled to board a train for Long Branch, NJ. When President Garfield, Secretary of State Blaine, and a bag carrier had taken a few steps into the carpeted room marked “ladies waiting area”, Guiteau shot Garfield from behind. The first shot grazed his victim’s arm, but the second shot went into the President’s back, piercing the first lumbar vertebra, but missing the spinal cord. Garfield was injured, but did not die on the scene. Guiteau was promptly arrested, jailed, and charged with attempted murder.

There’s a lot I could say here about what happened over the eleven weeks between Garfield’s shooting and his death, but we’ve got a lot of Guiteau to go, plus a very hefty section on the Performers coming up, so I will keep this extremely brief, and let you draw your own conclusions.

Garfield died on September 19, 1881, and Guiteau was charged with his murder. It took James A. Garfield eleven weeks to die from a single gunshot wound; one that would be easily survivable by almost anyone with access to healthcare practices that involve sterile instruments and surgeons with clean hands. Garfield didn’t have access to such luxuries, and spent eleven miserable weeks slowly departing this mortal coil. While Garfield obviously would not have died had he not been shot in the first place, the medical mistreatment may have done more damage to his body than the bullet did.

Part Two - He Tried to Play Off Insane

If I’ve done my job right, you should have enough information about Charles Guiteau to have drawn some conclusions about the man and his character.

Here’s my take. Guiteau was a troubled man. His mother suffered from some form of mental illness, and while I’m no diagnostician, it seems the apple didn’t fall far from the tree. He obviously had some delusions regarding the importance of his actions, and claimed to have been driven to act by God.

Guiteau was a mentally ill man with few attachments to other people. He was a perpetual outsider whose efforts at gaining respect or admiration of his peers always seemed to fall short of his aims.

I suspect his penchant for grandiosity didn’t win him any friends, and while I didn’t read his speeches in favor of Garfield, accounts are that these speeches were over the top fear-mongering affairs, replete with exaggerated claims about how failure to elect Garfield would result in another Civil War. Having read some of The Removal, Guiteau’s book about his trial, a text drenched in the grandiose delusions of a very disturbed man, I accept these assessments of Guiteau’s convention and campaign speeches at face value.

(NOTE: I won’t subject you to any of Guiteau’s writings because if you’ve heard or read one madman’s hollow, defiant claims about being persecuted, misunderstood, and/or on a mission from God, you’ve heard them all. For those with insatiably morbid curiosity, a link to The Truth and The Removal, the full texts of both Guiteau’s books, is in the Sources section of this article.)

Guiteau’s trial was an absolute circus. He used the trial as a performance opportunity, and regularly made a spectacle of himself. He wanted to represent himself in the trial, but he was required to have an attorney. The first court-appointed attorney resigned after Guiteau proved an impossible client to manage in the courtroom. Guiteau was ultimately represented by his brother-in-law George Scoville, a lawyer whose expertise was in land title examination.

This is one of the first high profile cases where the defendant claimed temporary insanity, and the crux of Guiteau’s argument was that anyone who claimed to act under direct orders from “the Deity” was insane. Since he thought himself to be acting under such orders at the time of Garfield’s murder, then he was clearly insane, and therefore, not guilty by reason of insanity.

Guiteau went on to say that the Deity needed him to murder Garfield because allowing Garfield to remain in the White House would cause another Civil War. (And yes, this is the same Guiteau who, one year prior, had warned of another imminent Civil War if Garfield didn’t become president.) Guiteau also said that because Garfield had died, (at the hands of the doctors and not by his bullet), the Deity’s Will was done, and the nation was saved from Civil War, thanks to the events Guiteau himself had set into motion.

The jury didn’t buy it. To them, Guiteau didn’t save the country from a second Civil War, and he wasn’t insane. He was just a murderer. On January 25, 1882, after deliberating the case for one hour, the jury found Charles Guiteau guilty of murdering James A. Garfield, then sentenced to be “hanged from the neck until dead” on June 30, 1882.

Part Three - Up on the Scaffold High

On the morning of his execution, Guiteau wrote a poem called "I Am Going to the Lordy". After climbing the scaffold to be hanged, Guiteau recited several Bible verses, warned the spectators that they would incur God’s wrath for hanging His noble servant, and then read/sang “I Am Going to the Lordy”.

Guiteau wanted an orchestra to back him up, but this request was denied. Guiteau also asked that the hangman cover his head, place the noose around his neck, and hang him as soon as Guiteau finished reading the poem and dropped the paper to the scaffold floor. The executioner honored this wish, and once the paper hit the floor, Guiteau’s head was covered, the rope secured around his neck, and the trap door beneath his feet promptly opened. The text of “I Am Going to the Lordy” is below.

I Am Going to the Lordy

I am going to the Lordy, I am so glad.

I am going to the Lordy, I am so glad.

I am going to the Lordy, Glory hallelujah!

Glory hallelujah! I am going to the Lordy!I love the Lordy with all my soul, Glory hallelujah!

And that is the reason I am going to the Lord. Glory hallelujah!

Glory hallelujah! I am going to the Lord.I saved my party and my land, Glory hallelujah!

But they have murdered me for it,

And that is the reason I am going to the Lordy. Glory hallelujah!

Glory hallelujah! I am going to the Lordy!I wonder what I will do when I get to the Lordy,

I guess that I will weep no more

When I get to the Lordy! Glory hallelujah!I wonder what I will see when I get to the Lordy,

I expect to see most splendid things,

Beyond all earthly conception,

When I am with the Lordy!

Glory hallelujah!

Glory hallelujah!

I am with the Lord.

NOTE: For the sake of completeness, I must mention that “The Ballad of Guiteau” in Stephen Sondheim’s musical Assassins includes interludes of “I Am Going to the Lordy”.

I’ve encountered countless poems and songs over the years. On some occasions, I’ve been underwhelmed when reading the text of a poem or song, yet blown away when hearing the piece performed live. There are, without question, certain pieces that only come to life in performance. I do not, however, believe “I Am Going to the Lordy” to be such a composition.

I find the word “Lordy” to be a horribly unnerving term to begin with. The mere notion of the word being repeatedly uttered by a man on the gallows is incredibly troubling. My distaste for the term may cloud my ability to examine this poem objectively. Having made my biases known, my humble assessment of this poem is thus; It is a mess, not unlike its author.

Coda - So what was this guy’s problem?

By now it’s clear that something was severely wrong with Charles Guiteau. What was it? How did he get that way?

There’s no simple answer. Human beings are complex creatures. Despite our notions of free will, who we are to become is not ours to control. Before we can exercise any significant free will, we are heavily influenced by our genetics and the environments in which we are raised. On both these fronts, the deck was stacked against Charles Guiteau. His mother had some form of mental illness and died when he was a boy. Add to this that he had speech difficulties and ADHD, (which probably made him an object of ridicule as a child), and we’ve got a maladjusted young man entering the world.

We know that in his twenties, Guiteau experienced sexual rejection and ridicule from others at Oneida. We know that the Republican Party didn’t want to take him seriously. We know that the Secretary of State told him to get lost. These events surely made Guiteau feel unwanted and thoroughly misunderstood. The lack of close connections left him with no one to turn to, and no one to trust, so Guiteau listened to the voices in his head.

His autopsy revealed that Guiteau had neurosyphilis, (an infection of the central nervous system caused by syphilis which can result in mental instability). This definitely would’ve played a role in his erratic behavior. The autopsy also revealed Guiteau to have phimosis, a condition whereby the foreskin never detached from the head of the penis. While not a direct cause of Guiteau’s mental instability, the frustration added by this condition did him no favors.

Others have argued that Guiteau had problems far beyond what could be revealed by an autopsy, and based on his behavior, have labeled him a schizophrenic with grandiose narcissism.

I would agree. Everything I’ve read about Guiteau indicates that he was plagued with severe mental health issues. Do I believe he was a narcissist? Absolutely. I’m all too familiar with the rantings of grandiose narcissists, and what I’ve read of Guiteau’s writing places him squarely among their ranks.

But at the end of the day, I pity Guiteau. From an early age, the world seemed to be working against him. He had very little going in his favor and never seemed to get a decent break in life. He was obviously an intelligent man, and he (at times) wanted to be good and righteous. Sadly, one can neither think nor pray their way out of mental illness.

After being hanged, Charles Guiteau’s body was buried in the cemetery by the jail house in Washington D.C. His remains were later exhumed and, according to FindAGrave, are now “in storage cabinets within the anatomical collections” in the National Museum of Health and Medicine in Washington DC. The storage cabinets are not open to the public.

The Performance

“Charles Giteau” opens somewhat clumsily. Posey Rorer’s fiddle leads the way, but R.D. Hundley and Albert Steagall stumble a bit before falling in with Rorer. The first verse is twice as long as the other verses, but it has to set the stage for what comes next, so the structure makes perfect sense. Harrell’s vocals are, as always, strong, clear, and believable.

When the chorus comes around, Harrell’s voice is joined by two other vocalists to deliver the hook. No other vocalist is credited on the label or listed in the DAHR record for this song, and that’s a damned shame. These added voices, which I suspect belong to Hundley and Steagall, bring this chorus to life, and once they appear, serve as the axis around which the song revolves until its conclusion. I daresay that the presence of multiple voices in the chorus is just as important to the overall impact of the song as any of the lyrics sung by Harrell.

While we’re on the chorus, I want to pause for a moment and appreciate the chorus’ lyrical beauty, particularly in the second half, where we encounter this gem.

But little did I think

While in my youthful bloom

I'd be carried to the scaffold

To meet my fatal doom.

These are some heavy lyrics, but these dark sentiments are delivered with glee by Harrell and company. This glorious juxtaposition is, to my ear, one of the Anthology’s musical peaks.

After the first chorus, we have a verse in which Guiteau’s sister comes in, lets us know why Giteau is being hanged, and departs. The glorious chorus returns, and then Alfred Steagall lays down a sizzling guitar solo where he leads us up the stairs with Guiteau, to the top of the scaffold where the hangman and gallows await in the final verse. From there, that epic chorus returns and the song winds down.

Kelley Harrell was one helluva singer. He had a good voice, spectacular phrasing, and immaculate timing. Behind Harrell, the powerhouse trio of Rorer, Steagall, and Hundley created a spectacular musical backing. Rorer is the glue throughout, but once Steagall and Hundley get cranked up, they become a solid rhythm machine. Harrell has said that this was the best band he recorded with, and I do agree.

This is a great record with some exceptional performances. Harrell’s vocal style is perfectly suited for the song, and the boys in the Virginia String Band are on point. They craft a fine musical backdrop for Harrell, sing (without credit) on the chorus, and then, for a special treat, Steagall’s guitar walks us up the scaffold before the hanging in the final verse. The end result is one of the finest proto-country records on the Anthology.

The Performers

NOTE: This is the third track in the Anthology on which fiddler Posey Rorer appears. His life is discussed in articles on the previous two songs on which he appeared (A Lazy Farmer Boy and My Name is John Johanna). No additional information about Rorer is contained in this article. The discussion of Rorer’s life will conclude when we get to “White House Blues” (the fourth and final song to feature Rorer on fiddle, and the other Anthology song about a Presidential assassination).

Kelley Harrell (Part Two)

(For the first part of Kelley Harrell’s story, see the article on “My Name is John Johanna”)

When we left off in the Kelley Harrell story, his recording career had yet to begin, but that’s where we’re going to get started today.

Kelley Harrell moved to Fieldale in 1924, and his recording career began on January 7, 1925, when he made four sides for Victor Records in New York City backed by studio musicians. In August 1925, Harrell went to the Okeh recording studios in Asheville, NC and recorded 12 sides backed by Henry Whitter on guitar, 8 of which were released. In June 1926, he recorded 13 sides for Victor in New York, backed again by studio musicians.

For the 1927 sessions, Victor agreed to let Harrell bring his own backing musicians into the studio. For his March 1927 sessions Harrell created the Virginia String Band, (which consisted of R.D. Hundley, Albert Steagall, and Posey Rorer). The March 1927 sessions produced both Kelley Harrell songs that appear on the Anthology of American Folk Music. For Harrell’s August 1927 sessions, he was backed by Hundley, Steagall, and Lonnie Austin. Henry Norton accompanied Harrell on vocals for two songs in this session. In February 1929, Harrell returned to the studio with Steagall to record six sides for Victor. These were Harrell’s final recordings. The Great Depression started later that year, and Harrell, unable to play an instrument, was no longer considered worth the investment by the record companies, so he returned to Fieldale and the textile mill. (NOTE: Kelley Harrell’s full discography, with links to recordings of each song follow the Sources section of this article.)

When the 1930 US Census was taken, Harrell was listed as working in the cotton mill, but had relocated his family to Horsepasture, Virginia. Harrell would remain in that general area for the rest of his life.

By 1940, Harrell and his family were still in Horsepasture, VA (just south of Fieldale, VA), but Harrell’s WWII draft card, completed on April 27, 1942, shows the Harrells lived on 7th Street in Fieldale, VA. His employer was Marshall Field and Company. (Marshall Field and Company owned Fieldcrest Mills, where Harrell worked. The company also owned the land on which the town of Fieldale, VA was built, and the houses in which workers lived).

Harrell was asthmatic, and on July 9, 1942, he was returning to work at the mill after being hospitalized. To demonstrate that he was still hearty and hale, Harrell leapt out of a window onto the path below. He landed on his feet, took a few steps, and fell to the ground. Kelley Harrell died en route to the hospital. He was 52 years old. His remains were buried in Oakwood Cemetery, in Martinsville, Virginia. His death certificate cites the cause of death as coronary thrombosis, due to “worker lint disease”, better known as byssinosis.

Hundley and Steagall

Prior to composing this article, the only information I could find about Alfred Steagall and R.D. Hundley came from recording info in the Discography of American Historical Recordings (DAHR), and Kinney Rorrer’s statement in his book about Charlie Poole that Kelley Harrell worked with Hundley and Steagall in Fieldale. I found no conclusive biographical information about banjo player R. D. Hundley or guitarist Alfred Steagall in any of the standard reference sources.

During my research for this piece, I uncovered genealogical, Census, and Draft registration information for two men named R.D. Hundley and Alfred Stegall who lived near and worked in Fieldale during the time that Kelley Harrell was actively recording. Both men had extensive obituaries, which helped tremendously, and I have independently confirmed that the two men discussed below are, in fact, the two men who played with Posey Rorer in the Virginia String Band.

R.D. Hundley

According to the DAHR, R.D. Hundley appeared in three recording dates with Kelley Harrell in 1927 (March 22, March 23, and August 12). Hundley played banjo on a total of thirteen sides with Harrell on vocals, and Alfred Steagall on guitar. The nine songs recorded in the March sessions featured Posey Rorer on fiddle. Lonnie Austin played fiddle on the four tracks recorded in August 1927. Each side upon which Hundley appeared was released, and all sessions in which he recorded were supervised by Ralph Peer.

Ramey Davis Hundley

R.D. Hundley’s name was Ramey Davis Hundley, and he was born in Henry County, Virginia on November 24, 1897. According to his World War I draft registration card, completed in 1918, the twenty year old Hundley was tall and slender with blue eyes and light colored hair and worked as a farmer around the unincorporated community of Horsepasture, in Henry County, Virginia. Two years later, the 1920 Census found Hundley married to Roxie Hundley, and living with her parents in Martinsville, VA where R.D. worked in a cotton mill.

When the 1930 US Census was taken, Hundley lived in Horsepasture with his wife Roxie and their three daughters,. At the time, he worked as a foreman at the cotton mill. His World War II draft registration card from 1942 has Hundley living in Fieldale, and working for Marshall Field Company (aka the cotton mill). In 1942, he stood 5’11” tall with brown hair, had a ruddy complexion, and wore glasses.

Hundley worked with Fieldcrest for over 30 years, and in the 1950’s he designed the Fieldcrest “Royal Velvet” towel. Although Fieldcrest no longer exists, the Royal Velvet towel line remains still in production as of this writing (July 3, 2025), and is exclusively available at J.C. Penney’s.

Hundley was a deacon in the Fieldale Baptist Church, and highly active in the community, He helped establish the YMCA in Fieldale, served as President of the Lions Club, and served a term on the Henry County Board of Commissioners in the 1970’s.

According to his obituary, R.D. Hundley died on March 11, 1991 in Martinsville, Virginia and is buried in Oakwood Cemetery in Martinsville. His tombstone specifically includes (R.D.), as he was referred to by his initials.

Alfred Steagall

According to the DAHR, Steagall played guitar on every recording that included R.D. Hundley on banjo. (See Hundley’s recording information above). In addition to the 1927 sessions, Steagall recorded 6 additional sides with Harrell on February 18 and 19, 1929. Five of those six sides were released, and Steagall ultimately appeared on 18 Kelley Harrell records.

As with R.D. Hundley above, I am 100% certain that the person I’ve located, Joseph Alfred Stegall, is the same man who appeared on Kelley Harrell’s 1927 and 1929 recordings and as Alfred Steagall.

Joseph Alfred Stegall

(NOTE: As I do with Kelley Harrell’s first name, I will use the spelling of Stegall’s last name as it appears on his tombstone from here on out. I have intentionally used “Steagall” up until this point to minimize confusion, but the proper spelling of his name is Stegall.)

Early Years

Joseph Alfred Stegall was born on July 26, 1905 in Henry County, Virginia, the eleventh and final child of James Alfred Stegall and Rosa Jane Minter. While seeking verifiable information about Stegall, I came across a website devoted to preserving Stegall’s memory, which proved an invaluable resource. If you finish this article and want even more insight into the life of this fascinating man, visit JAStegall.com.

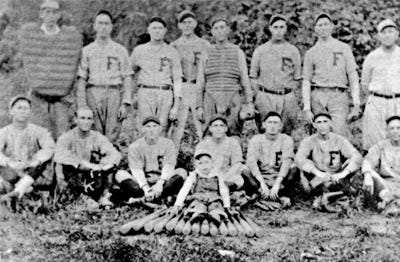

In his youth, Stegall had two passions, making music and playing baseball. It’s said he had a natural affinity for music and learned to play guitar at age 12. In 1927, when Stegall was 22 years old, his mother bought him a new Gibson guitar that was still in his family’s possession when the text on the tribute website was written.

While working at Fieldcrest Mills, Stegall met Kelley Harrell, who worked for Fieldcrest as a loom fixer. Harrell had already made records by this point, and was looking to form his own band. While we don’t know exactly how it came to pass, we do know that the Virginia String Band was born, with Stegall on guitar, R.D. Hundley on banjo, and Posey Rorer on fiddle. Harrell only recorded with this original lineup of the Virginia String Band in the March 1927 sessions.

Stegall was known to be fond of the recording of “In the Shadow of the Pine” he and the Virginia String Band made with Kelley Harrell on March 23, 1927. Interestingly, this was the second song recorded that day. The first song they recorded that day was “My Name is John Johanna”. “In the Shadow of the Pine” was second, and “Charles Giteau” was the third song recorded on that date. So, Stegall’s favorite recording was made in between the two that appeared on the Anthology.

Stegall indicated that he was with Kelley Harrell when Harrell sold the song “Away Out on the Mountain” to Jimmie Rodgers. Kelley Harrell wrote, but never recorded the song, and the sale could have occurred at either of the 1927 sessions in Camden, New Jersey. The song was recorded by Jimmie Rodgers on November 30, 1927, and by multiple artists in the years following.

Upon their return to Virginia, Harrell and the Virginia String Band performed in various local venues.

In February 1929, Stegall returned to the Camden, NJ studio with Harrell to record 6 sides (5 of which were released). Stegall earned $200 per side at this session. This was the last time Stegall or Harrell would ever record because the Great Depression put an end to the music careers.

Life after Harrell

Soon after returning to Virginia from his final recording session, Stegall married Lottie Virginia Sawyer on March 23, 1929. A few months later, Stegall fulfilled another childhood dream when he played his first game as a semi-professional baseball player, pitching for the Salisbury-Spencer Colonials in the Piedmont League. The 23 year old saw action in 27 games, but didn’t have an easy season. He ended the year with a win/loss record of 2-12 and an ERA of 5.13. Stegall struggled as a batter as well, ending the season with 11 hits (8 singles, 2 doubles, and one home run) over 57 at bats for an average of .193. The Salisbury-Spencer Colonials were a Class C minor league team, and ceased operations after the 1929 season.

When the 1930 US Census was taken, Stegall worked in the cotton mill, and he and his wife Lottie lived in Martinsville, VA with Stegall’s sister Berta and her husband Taylor Hundley (brother of R.D. Hundley), who was also an employee of the cotton mill.

In 1934, Stegall was on the baseball diamond once more, this time playing in the debut season of the Class D minor league Fieldale Virginians of the Bi-State League. Stegall had a much better season in 1934 than in 1929. He pitched 177 innings over 25 games, and ended the season with a win/loss record of 10-8 for a winning percentage of .556. No batting information was available for Stegall in 1934. In 1935, Stegall’s name was on the roster for the Fieldale Towlers, but there are no records of him having played in any games in that year.

According to Census data, by 1935, the Stegalls had moved out of Taylor Hundley’s and lived in Horsepasture, Virginia. In around 1939 or 1940, Stegall was asked by J. Frank Wilson, the mill’s general manager, to be the special officer for security until a proper constable could be hired. This wasn’t a typical situation, and Stegall wasn’t a typical security officer. As mentioned previously, the whole town of Fieldale was owned by the same company that owned the mill, and Stegall’s job duties were those that would be performed by the local law enforcement. One of his main directives was to make sure that bootleggers didn’t stop in the town. They could drive through, they just couldn't stop. It’s unclear how this happened, but Stegall’s beat grew to encompass the whole of Henry County, and he was the first police officer in the county to have a radio in his car. In 1940, the US Census shows Alfred working as a county police officer and living with his wife Bertie and their five children, (2 daughters and 3 sons).

On October 16, 1940 Stegall’s World War II draft registration card was completed. At this time, he was still a police officer employed by the Marshall Field Company (Fieldcrest), stood six feet tall, weighed 173 pounds, and had grey eyes and brown hair.

In the 1950 Census, Stegall was still in Fieldale, and still in law enforcement. Stegall patrolled Henry County and Fieldale for 57 years. By all accounts, he was a pillar in the community, and was honored by various organizations and civic clubs over the years. Stegall retired from law enforcement on his 85th birthday in 1990. His retirement celebration was attended by over 1,000 people, including State Senator Virgil Goode and Virginia State House Speaker A.L. Philpott.. Stegall was also a member of the Fieldale Rotary Club and an active member and Sunday School teacher at the Fieldale Baptist Church (where R.D. Hundley was a deacon).

Alfred Stegall died on April 25, 1993 in Martinsville, Virginia and was buried in Roselawn Burial Park in Martinsville, Virginia. In addition to the image of Stegall and his grave site below, his Find A Grave entry contains a lengthy obituary, from which some of the above information was gleaned.

But wait, there’s more

In 1931, an iron bridge was constructed over the Smith River in Fieldale. This bridge opened in 1932 and served the community until 2009, when it was replaced by a new bridge. A portion of the old iron bridge is now in Fieldale Park, and a plaque in Stegall’s honor is on the Iron Bridge Memorial.

Since 2010, several attempts have been made to rename the new Fieldale Bridge in Stegall’s honor. To date, these efforts have been unsuccessful. Should the bridge be renamed, I will update this article to reflect the change.

The above image of the Iron Bridge at Fieldale Park comes from Virginia.org. Plaques, like the one honoring Stegall, are attached to the lower beams and can be viewed when walking over the bridge.

Connections

This is the fifth song in the Timeline theme which began with “Peg and Awl” discussing events between 1801 and 1804, then went on to “Ommie Wise” which took place in 1807. From there, we time hopped to an undisclosed year in the 1870’s for “My Name is John Johanna” to close Side B. Side C resumed the theme with “Bandit Cole Younger”, which took place in the 1870’s, with the key event occurring in 1876. The events in “Charles Giteau” take place in 1881 (Garfield’s murder) and 1882 (Guiteau’s execution).

This is our fourth straight song to feature a person’s name in the title. This is the third song to feature fiddler Posey Rorer (“A Lazy Farmer Boy” and “My Name is John Johanna” being the other two).

This is the sixth of the past seven songs to feature some form of string ensemble. This is our 6th song that was recorded in a session overseen by Ralph Peer. (One Peer recording appeared on side A and 4 were on side B).

Other Interpretations

The Kossoy Sisters - Charles Giteau - This is exactly the same song recorded by Harrell and the Virginia String Band, performed by the Kossoy Sisters whose work I adore. This recording was the final track on their sophomore album Hop on Pretty Girls, which was released in 2002, over 40 years after their debut album came out. I’ve shared Kossoy Sisters’ recordings in previous articles, and cannot recommend their music highly enough.

A.L. Phipps and the Phipps Family - Charles Giteau - Faith, Love and Tragedy, the album on which this song appeared was the only Phipps family record to be released on Folkways. Though this album was recorded in 1965 by Ralph Rinzler (another name that will appear throughout Anthology Revisited), A.L. Phipps and family had been performing for many years before being finally captured on tape in 1960. They began performing in the 40’s as a trio with A.L., his wife Kathleen, and niece Hester Anderson. They initially had their own style and performed secular song, but they received so many requests for Carter Family songs, they became “Carter clones” (meaning a group that based their sound on the Carter Family, and could sound an awful lot like the Carters to folks who didn’t know better). For a while, the Phipps’ had a daily radio show in Kentucky, and appeared on other programs in Tennessee and West Virginia Their first albums (consisting of Carter Family covers) were released on Starday Records in the early 1960’s.

Meindert Talma - Charles Giteau - This is different. It comes from someone of whom I’d never heard prior to writing this article, but is a fascinating take, and shows how the Anthology’s influence is not limited to performers within the United States.

Meindert Talma is a lo-fi keyboardist and vocalist from the Netherlands. This track is taken from a 2006 album Nu Geloof Ik Wat Er in De Bijbel Staat (“Now I Believe what the Bible Says”) which contains 9 songs that appeared on the Anthology of American Folk Music sung in Dutch and performed with entirely different instrumentation. It’s really quite neat and quite different.

Conclusion

On the morning of June 30, 1881, Charles Guiteau was a desperate little man. In his four decades on the earth, nothing had ever seemed to go his way. Born to a mad mother who died when he was a child, Guiteau seemed to be set up for failure from the start. He tried, in his way, to do the right things and live a normal life, but he just couldn’t seem to find the place where he fit. His personality seemed to rub people the wrong way, and I found no instance in which Guiteau was considered a respectable (or even likable) individual. I find him a pitiful character. A very sad and very sick man about whom one can postulate a host of “what if’s?”. Could he have ever been a decent person? Did he possess the capacity for goodness? Did he possess the capacity for goodness while in his youthful bloom?

There’s a lot here, and we could go on for a very long time discussing Guiteau and folks like him, but we do have to wrap it up somewhere.

On the performer front, a lot of previously unreported (or under-reported) information appears in this article. I know I’m correct about Stegall (all the way down to his baseball stats), and have equal confidence in my conclusions about R.D. Hundley. Although this is already an exceptionally long piece, I have added a full discography of Kelley Harrell’s recordings (with links to audio on YouTube) as an Appendix to this article.

Next week, we’ve got another spectacular performance to discuss, and I can guarantee that I will not provide any previously unreported information about the performers, because the next song “John Hardy was a Desperate Little Man” was performed by the Carter Family, easily the best-known performers to appear on the Anthology of American Folk Music.

I’m wrapping up this mammoth piece as I always do, by reminding you that I didn’t just pull all this stuff out of the top of my head. I consulted many sources, and if you’d like to learn more about anything I’ve discussed in this article, the sources I consulted when writing this article are below.

In particular, I would like to extend my gratitude to Elva Adkins Adams who created, funded, and maintains JAStegall.com, an online resource devoted to the life and work of Joseph Alfred Stegall. Adkins also confirmed that Ramey Davis Hundley and R.D. Hundley were the same person via email.

AUTHOR’S NOTES: I’ve promised an appendix with a Kelley Harrell discography, and it’s coming up, but first, some programming notes. This Substack is a one-man operation. Anthology Revisited is a labor of love, and I am an independent writer trying to make his presence known by creating a work of substance that contributes to the corpus of knowledge. Your likes, restacks, and comments are tremendously appreciated. If you want to support my work (or contact me beyond the comments section), there are a few options.

You can subscribe to this Substack. You’ll receive these articles in your inbox, and all you have to do is click the “Subscribe now” button below and enter your email address in the box that appears.

You can pass this article along to someone else who might like it, via the “Share” button. I really hope you’ll do this. I know there’s an audience for this stuff, I just don’t know where to find them. If you know a person or group of folks who might find this interesting, kindly pass this article along.

This article is part of a series called Anthology Revisited, which is part of my publication, Rodney Writes about Music. To share this whole shebang with others, click the “Share Rodney writes about music” button below. (If you share the publication, the link will point to the landing page, where the introductory article for Anthology Revisited is prominently featured.)

I suck at asking for money, and I don’t have paid subscriptions enabled at the moment. But if you’d like to chip in to the “help Rodney pay the mortgage” fund, click the “Buy Me a Coffee” button.

If you’d like to offer any corrections to my content or contact me regarding Anthology Revisited, email me directly at rodney.hargis at outlook.com.

Now, without further ado, here’s that appendix I promised, followed by the Sources.

APPENDIX - Kelley Harrell Discography

1925 - JANUARY - Victor - New York City, NY

January 7, 1925

NOTE: In his first session for Victor Records, Kelley Harrell was backed by studio musicians on harmonica, violin, and guitar. The names of these performers were not recorded in studio logs.

New River Train

Rovin' Gambler

I Wish I Was a Single Girl Again

Butcher's Boy

1925 - AUGUST - OKeh - Asheville, NC

August 25, 1925

Personnel - Kelley Harrell (vocals), Henry Whitter (guitar, harmonica)

NOTE: For these sessions, Harrell was joined by guitarist Henry Whitter on guitar and harmonica. Whitter was already a recording artist for OKeh, and had released several sides of his own, as well as appearing as an instrumentalist on recordings by Roba Stanley.

I Was Born About Ten Thousand Years Ago

Wild Bill Jones

Peg and Awl

I Was Born in Pennsylvania

I'm Going Back to North Carolina

Be at Home Soon Tonight, My Dear Boy

August xx, 1925

Personnel - Kelley Harrell (vocals), Henry Whitter (guitar, harmonica)

NOTE: The exact date of this session is unknown. The previous session took place on Tuesday, August 25. The matrix number for the final song recorded in the previous session (“Be at Home Soon Tonight, My Dear Boy”) is 9277. The matrix number for the first song in this session (“The Wreck of the Southern Old 97”) is 9279. OKeh Matrix 9278 It’s possible that these songs were recorded on the same day as the other six sides, but they were probably recorded on August 26 or 27th.

The Wreck of the Southern Old 97

Blue-Eyed Ella

1926 - JUNE - Victor - New York City, NY

June 8, 1926

NOTE: This was Harrell’s second session for Victor. On the first day, he re-recorded the very same songs he recorded in his January 7, 1925 session. As in the first Victor session, Kelley Harrell is backed by studio musicians on guitar, fiddle, and harmonica whose names were not recorded in the studio logs.

New River Train

Rovin' Gambler

I Wish I Was a Single Girl Again

Butcher's Boy

June 9, 1926

O! Molly Dear, Go Ask Your Mother

Broken Engagement

The Dying Hobo

Beneath the Weeping Willow Tree

My Horses Ain't Hungry

Bright Sherman Valley

June 10, 1926

The Cuckoo, She's a Fine Bird

Hand Me Down My Walking Cane

Bye and Bye You Will Forget Me

1927 - MARCH - Victor - Camden, NJ

March 22, 1927

Personnel: Kelley Harrell (vocals), R.D. Hundley (banjo), Posey Rorer (fiddle), Alfred Stegall (guitar), Ralph Peer (session supervisor)

NOTE: This was the first time Harrell brought his own full band into the studio. Henry Whitter had accompanied Harrell in his 1925 sessions for OKeh, but for all his previous Victor sessions, Harrell used studio musicians. This was the first of two days to feature the original lineup of the Virginia String Band. Yes, I include Ralph Peer as part of the personnel. Listen to the quality of these recordings. I’m not just talking about performance, I mean the actual quality of the recording. When recording a room (rather than individual tracks), the physical placement of the musicians and the vocalist in relation to the microphones matters. An often overlooked aspect of Ralph Peer’s brilliance is his ability to physically arrange musicians in a room to get the best sound.

Oh, My Pretty Monkey

I Love My Sweetheart the Best

Henry Clay Beattie

I Want a Nice Little Fellow

March 23, 1927 - Victor - Camden, NJ

My Name is John Johanna

In the Shadow of the Pine

Charles Giteau

I'm Nobody's Darling on Earth

My Wife, She Has Gone and Left Me

1927 - AUGUST - Victor - Charlotte, NC

August 12, 1927

Personnel: Lonnie Austin (fiddle), Kelley Harrell (vocals), R.D. Hundley (banjo), Henry Norton (additional vocals where noted), Alfred Stegall (guitar), Ralph Peer (session supervisor)

NOTE: This is the second incarnation of the Virginia String Band. In this session, Lonnie Austin has replaced Posey Rorer on fiddle, and Henry Norton brought in as a supporting vocalist on two tracks.

Row Us Over the Tide (additional vocals by Henry Norton)

I Have No Loving Mother Now (additional vocals by Henry Norton)

For Seven Long Years I've Been Married

Charley, He's a Good Old Man

1929 - FEBRUARY - Victor - Camden, NJ

February 18, 1929

Personnel: Kelley Harrel (vocals), Alfred Stegall (guitar)

Are You Going to Leave Your Old Home Today? (Unissued)

The Henpecked Man

February 19, 1929

Personnel: Sam Freed (violin), Kelley Harrel (vocals), Alfred Stegall (guitar),

She Just Kept Kissing On *

All My Sins Are Taken Away * (variant of “Hand Me Down My Walking Cane”)

Cave Love Has Gained the Day

I Heard Somebody Call My Name

*Roy Smeck (harmonica and jaw harp)

Sources

The Trial of Charles Guiteau: An Account

by Douglas O. Linder (2007)

https://web.archive.org/web/20090802174404/http://www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/FTrials/guiteau/guiteauaccount.html

The Truth and The Removal

Guiteau, Charles

1882

https://archive.org/details/truthremoval00guit/page/n107/mode/2up?view=theater

Charles J. Guiteau - Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_J._Guiteau

Oneida Community - Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oneida_Community

I Am Going to the Lordy - Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/I_Am_Going_to_the_Lordy

Charles Julius Guiteau - FindAGrave

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/429/charles_julius-guiteau

Kelly Harrell - Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kelly_Harrell

Crockett Kelley Harrell - World War I Draft Card

https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:7D73-336Z

"United States, World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918", FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:7D73-336Z : Tue Apr 29 06:24:55 UTC 2025), Entry for Kelley Crockett Harrell, from 1917 to 1918.

Crockett Kelley Harrell - Death Certificate

https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QVRZ-1V48

"Virginia, Death Certificates, 1912-1987", FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QVRZ-1V48 : Tue Mar 11 05:21:46 UTC 2025), Entry for Kelley Crocket Harrell and William Harrison Harrell, 25 Jul 1942.

Crockett Kelley Harrell - FamilySearch

https://www.familysearch.org/en/tree/person/about/LT63-QTP

Crockett Kelley Harrell - FindAGrave

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/33650382/crockett_kelley-harrell

Byssinosis - Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Byssinosis

Rambling Blues - The Life and Songs of Charlie Poole

Rorrer, Kinney

1982 - McCain Printing Co. Inc,

Danville, VA

Ramey David Hundley (1897-1991) - FamilySearch

https://www.familysearch.org/en/tree/person/about/G94C-RDB

Ramey Davis Hundley Draft Registration 1917-1918, World War I, Henry County, Virginia

https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9YYN-9HDK?view=explore

"United States records," images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9YYN-9HDK?view=explore : Jun 29, 2025), image 1472 of 3287; United States. National Archives and Records Administration,United States. National Archives and Records Administration. Atlanta Branch. Image Group Number: 005153693

Reamy D Hundley | United States Census, 1920

https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MJFG-JD7

"United States, Census, 1920", FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MJFG-JD9 : Sun Jan 19 20:10:02 UTC 2025), Entry for James A Stegall and Rosa J Stegall, 1920.

Reamy D Hundley and Roxie B Hundley | United States, Census, 1930

https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:CXM9-6ZM

"United States, Census, 1930", FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:CXM9-6ZM : Mon Jul 08 00:57:53 UTC 2024), Entry for Reamy D Hundley and Roxie B Hundley, 1930.

Ramey Davis Hundley | Virginia, World War II Draft Registration Cards, 1940-1945 Henry County, Virginia

https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:Q2WR-3XBD

"Virginia, World War II Draft Registration Cards, 1940-1945", FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:Q2WR-3XBD : Tue Apr 29 15:09:20 UTC 2025), Entry for Ramey Davis Hundley and R D Hundley, 16 Feb 1942.

Ramey Davis - Obituary

https://images.findagrave.com/photos/2020/115/74901977_e100adaa-2de6-41cc-86b1-ccfe6afa8a40.jpeg

Ramey Davis “R D” Hundley (1897-1991) - Find a Grave Memorial

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/74901977/ramey-davis-hundley

R.D. Hundley | Discography of American Historical Recordings

https://adp.library.ucsb.edu/index.php/mastertalent/detail/322188/Hundley_R._D

Alfred Steagall | United States Census, 1930

https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:CXMQ-46Z

"United States, Census, 1930", FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:CXM3-93Z : Sat Jan 11 16:19:19 UTC 2025), Entry for Taylor M Hundley and Bertie Hundley, 1930.

Alfred Stegall | United States Census, 1940

https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:VRB4-QPR "United States, Census, 1940", FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:VRB4-QPR : Wed Jan 22 07:28:48 UTC 2025), Entry for Alfred Stegall and Lottie Stegall, 1940.

Joseph Alfred Stegall | Virginia, World War II Draft Registration Cards, 1940-1945

https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:Q2W5-FQR6

"Virginia, World War II Draft Registration Cards, 1940-1945", FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:Q2W5-FQR6 : Tue Apr 29 15:20:18 UTC 2025), Entry for Joseph Alfred Stegall and Lottie Virginia Stegall, 16 Oct 1940.

Chief Joseph Alfred Stegall (1905-1993) - Find a Grave Memorial

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/79230588/joseph-alfred-stegall

BVE-38237-Charles Giteau/Kelly Harrell | Discography of American Historical Recordings

https://adp.library.ucsb.edu/index.php/matrix/detail/800012495/BVE-38237-Charles_Giteau

Kelly Harrell - Discography of American Historical Recordings

https://adp.library.ucsb.edu/index.php/mastertalent/detail/108363/Harrell_Kelly

Posey Rorer - Discography of American Historical Recordings

https://adp.library.ucsb.edu/index.php/mastertalent/detail/108572/Rorer_Posey

R. D. Hundley - Discography of American Historical Recordings

https://adp.library.ucsb.edu/index.php/mastertalent/detail/322188/Hundley_R._D

Alfred Steagall - Discography of American Historical Recordings

https://adp.library.ucsb.edu/index.php/mastertalent/detail/209792/Steagall_Alfred

Joseph Alfred Stegall - The Early Years

https://jastegall.com/early-years.php

Joseph Alfred Stegall - Stories about Stegall

https://jastegall.com/stories-about-stegall.php

Joseph Alfred Stegall - Plaque in memory of J.A. Stegall

https://jastegall.com/plaque.php

Iron Bridge at Fieldale Park

https://www.virginia.org/listing/iron-bridge-at-fieldale-park/4089/

Alfred Stegall Minor Leagues Statistics | Baseball-Reference.com

https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/player.fcgi?id=stegal001alf

Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music - America Changed Through Music

Edited By Ross Hair, Thomas Ruys Smith

Chapter 9. Dead Presidents: "Charles Guiteau", "White House Blues", and the Histories of Smithville Thomas Ruys Smith

Routledge, 2017

p. 162

“The liner notes of Kelly Harrell: Complete Recorded Works in Chronological Order Volume 2 (1926-1929) written by Tony Russell include this anecdote about Harrell’s final moments.

[He] suffered from asthma, and one day, back at work after a spell in hospital, chose to prove his fitness to his workmates by jumping out of a window on to the path not far below. He landed, took a few steps and collapsed. He died on the way to hospital, on July 9, 1942, aged 52.”

NOTE: Due to the peculiar nature of this citation, (it appeared in the text exactly as quoted above), I felt it necessary to include both my source and the source’s source for complete transparency.