Willie Moore by Dick Burnett and Leonard Rutherford [Anthology Revisited - Song 10]

TL;DR -- Willie and Anna hope to wed. Parents say no. Sorrow ensues. Performers partnership endures despite little recorded evidence. Burnett never records his most famous composition.

Welcome to the tenth installment in Anthology Revisited, a song-by-song journey through the Anthology of American Folk Music, an iconic collection assembled by Harry Smith and released on Folkways Records in 1952. Today, we’re examining “Willie Moore”, the first song on the Anthology to originate in the United States. It’s another ballad of courtship and it’s performed by the phenomenal duo of Dick Burnett and Leonard Rutherford, a pair whose talents merited a much wider audience and greater acclaim than they enjoyed.

Before we get going, I want to give a little heads up. The song we’re examining today involves an assumed suicide. There are no graphic descriptions of the act, but I don’t think it’s a cool to surprise people with such a sensitive topic when they’re just trying to read an article about a folk song.

The first nine songs on the Anthology originated in the British Isles. It begins with Child ballads then transitions to other ballads, all of which come from England, Ireland, or Scotland. This song is a 100% American ballad with no lyrical connection to foreign ballads.

This is our fifth consecutive song about courtship. This time, the courtship goes smoothly, hits a snag, and things turn tragic.

How tragic? I’ll let Harry Smith’s headline answer that question.

ANNIE UNDER GRASSY MOUND AFTER PARENTS NIX MARRIAGE TO KING. DEATH PROBABLY SELF INFLICTED

Harry’s headlines often contain the entire song compressed into a single sentence, and here, while most details are skipped, the whole story is in the first sentence. Smith’s headline then suggests that Anna killed herself.

Smith is right, of course, and while suicide is never openly mentioned in the song, but there’s no hunt for the “real killer”, and no murder accusations hurled at Willie Moore, which leaves only one logical option for explaining her death.

Lyrics

Willie Moore was a king, his age twenty-one,

He courted a damsel fair;

O, her eyes was as bright as the diamonds after night,

And wavy black was her hair.

He courted her both night and day,

‘Til to marry they did agree;

But when he came to get her parents consent,

They said it could never be.

She threw herself in Willie Moore’s arms,

As oft time had done before;

But little did he think when they parted that night,

Sweet Anna he would see no more.

It was about the tenth of May,

The time I remember well;

That very same night, her body disappeared

In a way no tongue could tell.

Sweet Annie was loved both far and near,

Had friends most all around;

And in a little brook before the cottage door,

The body of sweet Anna was found.

She was taken by her weeping friends,

And carried to her parent’s room,

And there she was dressed in a gown of snowy white,

And laid her in a lonely tomb.

Her parents now are left all alone,

One mourns and the other one weeps;

And in a grassy mound before the cottage door,

The body of sweet Anna still sleeps.

This song was composed in the flowery West

By a man you may never have seen;

O, I’ll tell you his name, but it is not in full,

His initials are J.R.D.

NOTE: Transcribing this was no easy task, as there are several places where the words are quite difficult to determine. In the seventh verse, for example, is it a gown of snowy white or a shroud of snowy white? And those initials at the end… is the last letter D or G? I slowed down the recording, and listened to it several times over. I’m leaning towards the initials being JRD, but this is just speculation.

The Song

Usually, this section examines the history of the song, reviewing previous versions of the text to show how the song evolved over time to become the song we hear on Smith’s Anthology. But this song is a unlike prior songs we’ve discussed because we have no antecedents to which we can compare this song. Since the oldest version of the song is on the Anthology, we’re going to examine the Burnett and Rutherford version, then check out a version of the song that appeared after the recording.

Although this is the first song on the Anthology to originate in the USA, the song’s opening words “Willie Moore was a king”, throw a question mark at the song’s supposed American roots.

But Willie Moore was not the kind of king who had royal ancestors and ruled over his subjects. That line is saying Willie Moore was a gem of a human being, a stand-up guy, a hardworking, reliable, righteous young lad of twenty-one years who would make a fine catch for any young lady.

The first verse and the first half of the second verse make it clear that Willie and Anna were in love with one another and had been seeing each other for some time. In the second verse, Moore proposes, Anna accepts, but Anna’s parent’s refuse to allow the wedding. In verse three, Anna is distressed by her parent’s refusal and seeks comfort in Willie’s arms. Shortly afterwards, Moore leaves for the evening, never to see Anna again. In the fourth verse, things get dark and cryptic. The first two lines tell us that these events occurred on or about May 10th, but the last two lines are bone-chilling:

That very same night, her body disappeared

In a way no tongue could tell.

To me, the line “In a way no tongue could tell” indicates that no one saw what happened, which means Anna wasn’t murdered because if she’d been killed by another, the killer could tell what happened. That leaves only one option, Anna killed herself, and no one is really sure how she did it.

The fifth verse begins by recounting how Anna was well-loved by her friends, and ends with her corpse being found in a brook right in front of her parents’ home. In verse six, Anna’s friends take her body into her parents’ house, dress her and lay her to rest. Verse seven tells us that Anna’s parents are alone and heartbroken while their daughter's remains lie beneath the ground just outside their house. The eighth and final verse is a strange non-sequitur. The narrator, having told the tale, gives hints to the song’s origins. Unfortunately, the main clue we’re given regarding the identity of the song’s composer is incomprehensible. Are the composer’s initials JRD or JRG?

Sources indicate that Burnett and Rutherford learned the lyrics to “Willie Moore” from a broadside (called a “ballet” in rural Kentucky), a statement which tracks with the weird final verse. Printed broadsides would occasionally include verses that identified the author, but such verses which were usually discarded by performers, but, for reasons unclear, Burnett and Rutherford chose to keep this one.

The lyrics were found on a ballet (broadside), and Burnett and Rutherford paired the lyrics with part of a floating tune commonly associated with Child ballad 74 “Sweet William and Lady Margaret” (aka “Fair William and Lady Margaret”), a song that goes back to at least the 1700’s, and may have roots in the 1600’s.

You can hear the connection in this version of “Sweet William and Lady Margaret” performed by Jean Ritchie. The musical relationship between the songs should be immediately evident. We don’t have any other information about the origins of “Willie Moore”, so I must simply rely on the performers’ accounting. But I would surely love to see that broadside.

That Other Version of “Willie Moore”

According to Smith’s liner notes, the lone printed reference to the song appears in Vance Randolph’s Ozark Folksongs Volume IV. Smith’s liner notes mention the introductory text that preceded the song in Randolph’s book, but omit a couple of key details. First, the meeting between the farmer and the preacher who claimed to be Willie Moore occurred in 1936, 9 years after Burnett and Rutherford recorded the song. Secondly, Randolph collected his version of the song in 1941, 14 years after the Burnett and Rutherford recording was made.

Randolph’s entire book is available on the Internet Archive, and the text below was copied from that source. The emphasis on the third and seventh verses were added by this author.

WILLIE MOORE

Mr. Paul Wilson, Farmington, Ark., met a Reverend William Moore in Dallas, Texas, in 1936, who claimed that this song was written about him. "I sure did have some misadventures when I was young," Moore was quoted as saying. "I didn't go to Montreal and die, though, like the song says. I just went to East Texas, an' took up preachin' the Word."

(Sung by Mr. Fred Starr, Greenland, Ark., Oct. 8, 1941.)

Willie Moore was young, he was scarce twenty-one,

When he courted a damsel fair,

Her eyes were like two diamonds bright,

And raven black was her hair.He courted her both day and night

Until to marry him she did agree,

But when they went to get her parents' consent

They said this could never be.But I love Willie Moore, she told herself,

Far better than I love my life,

I had much rather die than to weep and sigh

That I never can be his wife.That very same night sweet Annie disappeared,

And they searched the country around,

Until at length in a brook near her father's house

The body of Annie was found.Her mother and father live all alone,

One weeps while the other mourns,

And in front of the door is a little green mound

Where the body of Annie lies now.Willie Moore scarcely spoke that any one knew,

And at length from his friends did part,

The last heard of him he was in Montreal

Where he died of a broken heart.

This version contains fewer verses than Burnett and Rutherford’s recording, but provides a bit more clarity. The third verse of this version discusses Anna’s state of mind, adding credence to the notion of a suicide, and the final verse of this song tells us what may have happened to Willie Moore.

The Max Hunter Folk Song Collection contains two recordings of Willie Moore, but neither of those offer us any new information. The first recording is sung by Mr. Starr in 1958 (the same man from whom Randolph collected the song in 1941), and adheres to the text from Randolph’s book. The second recording is from 1975 and uses the same lyrics as Burnett and Rutherford’s recording.

The Performance

Recorded in Atlanta, Georgia for Columbia Records on November 3, 1927, with Dick Burnett (vocals, banjo) and Leonard Rutherford (fiddle), this recording of “Willie Moore” is the oldest known version of the song,

This section typically covers how this recording differs from previous versions of the song, either in text or on record, but since no such recordings or texts exist, we’ve already examined the text of the song as performed by Burnett and Rutherford, there’s not much to say on that topic.

Instead, I want to discuss the performance itself, specifically the musicianship on display in this recording, as it ties directly into our next section on the performers. When I listen to this recording, I’m especially struck by how closely Burnett and Rutherford listen to and play off of each other. It’s apparent that these two guys have played together regularly. From the start, they play as one, and their precision endures throughout the recording.

Burnett holds the whole thing together, keeping time on the banjo and singing while Rutherford slides in and out with the fiddle to add a lovely texture to the melody. Did they rehearse the song? Absolutely, but there’s more to this than just practicing the number. These two musicians are in tune with each other. They listen closely to each other and react in kind. There are a couple of moments in the later verses of the song where Rutherford slips slightly off beat for a hot second, but he’s so quick to get back into the groove that these missteps are hardly noticeable.

For comparison, in “Fatal Flower Garden” and “Old Shoes and Leggins” (the only other pieces we’ve covered that include multiple instrumentalists), while neither song has glaring issues, close listens reveal the performances to be far less precise in execution than Burnett and Rutherford’s performance.

“Fatal Flower Garden” has fluctuations in the timing throughout, although some fluctuations could be due to warping on the physical copy of the record Smith used when compiling the collection. The slide and the guitar fall slightly out of sync on occasion, and the slide even hits a bad note in there.

Similarly, “Old Shoes and Leggins” features four musicians who work quite well together, but there are points where someone goes a bit off. Ernest Stoneman’s harmonica hits a couple of bad notes, and Hattie Stoneman’s fiddle goes off-tempo on a couple of occasions. It’s nothing catastrophic, and it requires close listening to even detect, but it’s there.

In “Willie Moore”, the musical interplay feels natural. Burnett and Rutherford play the song with the kind of synchronicity that emerges when musicians have played together frequently enough to innately know each other’s idiosyncrasies. As the next section reveals, the two had been playing together for over a decade when they made this recording, so there’s a valid reason to think they sounded in tune with one another.

The Performers

In 1914, Dick Burnett, a blind singer and banjo player from Monticello, Kentucky, hired a teenager, Leonard Rutherford, to be his sighted companion and accompany him to a performance at the Laurel County (Kentucky) Fair. Apparently, Rutherford proved a good companion because he continued to travel with Burnett until 1950. In time, Rutherford learned to play fiddle, and accompanied Burnett not only in his travels, but also joined him on stage and later in the recording studio. Between 1926 and 1928, the pair released 17 sides together, and had a much larger impact than their meager recorded output would suggest.

Richard Daniel Burnett was born a few miles outside of Monticello, Kentucky in 1883. Burnett’s father died when he was four years old, and his mother died when he was 12, and I’ll tell you now, this is a fella who was no stranger to tragedy. Burnett learned to make music at an early age, picking up the dulcimer at 7, the banjo at 9, and the banjo and guitar by the time he was 13. In addition to being a vocalist and multi-instrumentalist, Burnett was also a songwriter.

Losing both his parents at such a young age meant Burnett went to work young. He worked in various industries in the area, and got married in 1905. In 1907, a mugger attacked him and stole his money. Burnett put up a fight and the gun went off near his face, blinding Burnett. Surgical efforts to restore his eyesight failed, and Burnett was left to support himself and his family as a musician. Paying gigs weren’t exactly easy to come by in rural Kentucky, so Burnett walked or took trains to play for tips in public areas.

The Wayne County Courthouse in Monticello had a large shaded lawn which was a regular venue for Burnett and other local performers. Railroad stations, street corners, and other places where people would naturally gather also served as Burnett’s venues. Being blind, and having already been the victim of a violent robbery, Burnett didn’t leave a hat on the ground for people to leave him tips. Instead, he had a tin can strapped to his leg into which folks would leave tips.

In addition to performing, Burnett also sold copies of his lyrics. Although typically distributed on “ballets” (broadsides), Burnett would occasionally create and sell songbooks that contained songs from his performances.

In 1913, he published such a songbook with six songs, most of which originated from other singers, but two of the songs came from Burnett’s own hand. The first, “Song of the Orphan Boy”, was a semi-autobiographical piece that Burnett later recorded but which was never released. The second song, called “Farewell Song” was never recorded by Burnett, but it was recorded by Burnett’s friend Emry Arthur in 1928, and released with the title of “Man of Constant Sorrow”, perhaps you’ve heard of it.

Leonard Rutherford was born in or about 1898 in Somerset, Kentucky, and lived in Monticello most of his life. In Monticello, Rutherford met Dick Burnett, and in 1914, Burnett asked Rutherford to be his sighted assistant on a trip to the Lauren County (Kentucky) Fair. This was the beginning of a longstanding relationship between the two. Both of Rutherford’s parents died when he was a teenager, and the young man spent more time with Burnett, learning to play various instruments and accompanying Burnett on his travels.

Rutherford’s skills quickly improved, and the duo of Burnett and Rutherford traveled by horse, bus, and train to perform throughout the region. In time, Burnett purchased a car, and with Rutherford at the wheel, the pair traveled (in the words of Burnett) “from Cincinnati to Chattanooga” and played “every town this side of Nashville”.

After a performance in the Bonny Blue Coal Camp, Virginia, a general store owner who recognized quality work when he heard it, encouraged the pair to get recorded because he wanted to sell their music in his store. The duo followed his suggestion, and Frank Walker (a Columbia records A&R manager) invited them to a “field recording” session for Columbia Records in Atlanta, Georgia.

Discography

During their studio sessions, Burnett would play guitar or banjo, depending on the song, but Rutherford always played fiddle. Both men sang, although Burnett took most of the lead vocals. For each of the tracks listed below, I’ve noted who sang, what instrument Burnett played, and added a few bits of information that may be of interest.

The First Columbia Session - On November 6, 1926 in Atlanta, Georgia, Burnett and Rutherford recorded their first six sides for Columbia, all of which were released by the label.

“Lost John” (Rutherford - vocal , Burnett - guitar) - this recording sold over 37,500 copies in the 3 years after it was released. (And it’s no wonder. The extended instrumental break is smoking hot). The sales numbers were a big deal at the time, and the record’s success led Frank Walker to record and release more authentic southern artists.

“Little Stream of Whiskey” (Rutherford - lead vocal, Burnett - guitar, vocal)

“Weeping Willow Tree” (Rutherford - vocal, Burnett - guitar, lead vocal)) - This song was later popularized by the Carter Family as “Bury Me Under the Weeping Willow”

“I’ll Be With You When the Roses Bloom Again”(Rutherford - vocal, Burnett - guitar, lead vocal)

“A Short Life of Trouble” (Burnett - banjo, vocal) This one has been done by a bunch of other folks, including Flatt and Scruggs and Doc Watson.

“Pearl Bryan” (Burnett - guitar, vocal)

The Second Columbia Session - 4/2/27 Atlanta - Columbia

“My Sweetheart in Tennessee” (Burnett - guitar, vocal)

“Are You Happy or Lonesome?” (Rutherford - vocal, Burnett - banjo, vocal)

“Assassination of J.B. Marcum” (unissued)

“Song of the Orphan Boy” (unissued) - One of Burnett’s original songs.

The Third Columbia Session 11/3/27 - Atlanta - Columbia

“Curley-Headed Woman” (Burnett - banjo, vocal) - If you know the song “Hesitation Blues”, this might sound very familiar.

“Ramblin’ Reckless Hobo” (Rutherford - lead vocal, Burnett - banjo, vocal)

“Willie Moore” (Burnett - banjo, vocal)

“All Night Long Blues” (Burnett - guitar, vocal)

“Ladies on the Steamboat” (Burnett - banjo, speech and sound effects)

“Billy in the Low Ground” (Burnett - banjo, speech, and sound effects)

While the pair’s Columbia recordings sold well, but the only payment Rutherford and Burnett received was $60 per side recorded, plus travel expenses. They received no royalties or residuals from Columbia, but they did manage to earn a little extra money from the records because Burnett purchased copies of their records wholesale to sell at their concerts. The pair left Columbia and recorded with Gennett records, based in Richmond, Indiana (far closer to Monticello, Kentucky than Atlanta). Despite the relative proximity of Gennett’s studio, only three Burnett and Rutherford recordings would be released by the company.

The First Gennett Session - 10/29/28 - Richmond, Indiana. These were the final recordings made by Burnett and Rutherford, all sides included Byrd Moore on guitar. From these 1928 Gennett sessions, two additional sides featuring Burnett on banjo, Byrd Moore on guitar and Dick Taylor on fiddle were also released.

“She is a Flower from the Fields of Alabama” (Burnett - banjo, vocal)

“Under the Pale Moonlight”(Rutherford - lead vocal, Burnett - banjo)

“The Spring Roses” (unissued)

“Cumberland Gap” (Burnett - banjo, vocal)

Burnett returned to Gennett studios in 1929 for a session that yielded three sides with Lynn Woodard on fiddle. In 1930, Gennett released two more songs recorded by Burnett with Oscar Rutledge on guitar.

Rutherford teamed up with guitarist and vocalist John Foster for a 1928 session for Gennett which yielded no releases. Rutherford and Foster returned to Gennett for five more sessions in 1929 and 1930 in which they cut 21 sides. Their recording of “Six Months Ain’t Long” was one of the best selling recordings of the time. They made four recordings for Brunswick Records in 1930,

Rutherford suffered from epilepsy, which brought his partnership with Foster to an end in 1930. But, as mentioned previously, Leonard Rutherford continued to tour and perform with Dick Burnett until 1950.

Post-Recording Years

For folks yearning to know what Burnett and Rutherford sounded like after their recording sessions, I have bad news. This is the end of the line for their recordings, even though they continued to perform together for two more decades. In this author’s opinion, the few recordings Burnett and Rutherford made together scarcely do their talents justice. They made some damn good records, and suspect they only improved from there.

By all accounts, they knew how to put on a show. Well… Burnett knew how to put on a show. In reading up on the duo, I learned that one of Burnett’s complaints about Rutherford was that he lacked a strong stage presence, and an affinity for showmanship. Burnett, on the other hand, would work the crowd and use various non-musical noisemakers to bring a little of what he called “monkey business” into the act. If you listen to some of the recordings above, you can hear some of Burnett’s “monkey business” in action.

Burnett was serious about music even before he lost his eyesight. He was both a songwriter and a song collector with an expansive repertoire. When asked where he learned the old songs he’d recorded, he said he’d learned them from Monticello and Wayne County locals, specifically citing Bled Coffee and Cuje Bertram, two African-American performers from the area, Coffee, according to Burnett “played fiddle in the Civil War”. Despite the segregated nature of the times, Bertram would play with Burnett in front of the Monticello Court House, and helped Rutherford improve his fiddle skills.

So with all of this, I really think these two were an especially solid live act, even though we’ll never know. I imagine that Burnett’s charismatic stage presence and zeal for performing were quite captivating. The recordings clearly show that Burnett and Rutherford had a tightness to their sound. Add to this that Burnett was songster and a songwriter, with a tremendous well of songs from which to draw and keep their audiences engaged. It’s a shame that no complete live concerts from Burnett and Rutherford were ever recorded.

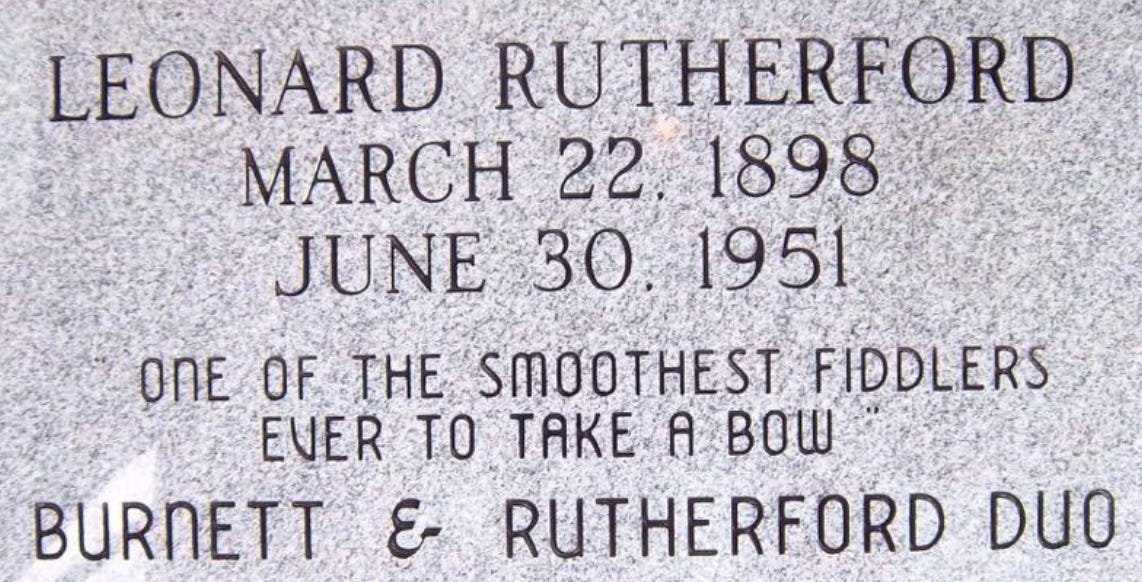

The Inevitable

Due to complications from epilepsy, Rutherford died in 1951, leaving behind a wife and two children. His body was buried in an unmarked grave by his brother-in-law. A donated headstone honoring Rutherford was placed in Somerset City Cemetery in Somerset, Kentucky.

Dick Burnett was (and hopefully remains) revered by the good people in the Monticello area. Sadly, he didn’t leave behind a wealth of recordings, but his contributions left a permanent mark on American music just the same.

Dick Burnett, the man who wrote “Man of Constant Sorrow”, died on January 23, 1977, leaving behind his wife of 72 years, Georgianna. His remains were laid to rest in Elk Spring Cemetery in Monticello, Kentucky.

Connections

“Willie Moore” is the fifth consecutive song in the Anthology of American Folk Music to deal with the theme of courtship. Throughout the courtship sequence, each song has described a different possible outcome of courtship.

In “The Butcher’s Boy”, the courtship is ended due to the young man’s infidelity. In “The Wagoner’s Lad”, the girl’s parents don’t care for the titular character, and since they cannot marry, the courtship ends with his departure.

The courtship of the frog and mouse in “King Kong Kitchie Kitchie Ki-Me-O” ended in marriage, while in our previous number, “Old Shoes and Leggins”, the courtship never even got off the ground because the young ladies found the old man too bizarre for their tastes

Here, with “Willie Moore” there’s a familiar outcome, but the conclusion is reached for a different (yet familiar) reason. Sweet Anna takes her own life, not because Willie is unfaithful (as was the case in “The Butcher’s Boy”), but rather because her parents won’t permit her to marry the boy she loves (as in “The Wagoner’s Lad”).

As far as other connections go, “Willie Moore” is the second consecutive song to feature multiple instrumentalists. As mentioned previously, it was the first ballad not to have descended from an English, Irish, or Scottish ballad.

Other Interpretations

Jean Ritchie and Doc Watson - Willie Moore - When writing about “The House Carpenter”, I was delighted to share a version of the song from the album Jean Ritchie and Doc Watson at Folk City. I do love the record, and I’m happy to have a reason to share another track from the album. There’s no dramatic departures here, just the song we’ve come to know throughout the article, performed in concert by Doc Watson and Jean Ritchie in 1963. Don’t be surprised if a couple more recordings from this album appear in this series.

The Kossoy Sisters - Willie Moore - Having just confessed my adoration of Jean Ritchie and Doc Watson at Folk City, I must confess that I have even greater love for the Kossoy Sisters’ 1956 LP Bowling Green and Other Folk Songs from the Southern Mountains. Singing siblings are capable of producing some breathtaking harmonies, and we’ve got tons of recordings that bear this out. Listen to practically anything by the Louvin Brothers, the Everly Brothers, or the Andrews Sisters, and you’ll see what I mean. The Kossoy Sisters are identical twins, and their biological similarity makes for some next level harmonies. Kossoy Sisters recordings will continue to appear as we go through the Anthology.

(SIDEBAR; if you’re not familiar with the Kossoy Sisters’ version of “Bowling Green”, you should remedy that as soon as possible. The song doesn’t appear on the Anthology, and its mention in this article is a bit out of bounds, but it’s one helluva recording, and it’d be a shame if no one ever told you about it.)

Joan Baez - Willie Moore - recorded sometime between 1960 and 1963, this live performance of Willie Moore by Joan Baez is in line with the others we’ve heard. It doesn’t cover any new or different ground. The track contains the “Montreal” verse omitted by Burnett and Ruterford and ends with the first verse being repeated.

David Grisman Experience - Willie Moore - This modern string band version of Willie Moore was recorded in 2013. While lyrically no different from the other recordings, it’s fun to hear this song as performed by a larger group and recorded with high quality modern equipment.

Conclusion

We’ve covered a lot of ground here with our first all-American ballad, and I hope you’ve enjoyed this exploration into “Willie Moore” and the music of Burnett and Rutherford as much as I have. Although I will admit I was bummed to learn that Burnett and Rutherford toured together for 20 years after their final recording sessions, and never recorded again. Even the mighty Lomax Family, who captured many great performances over the years, failed to preserve any work by these two. That’s a shame.

Next week, we’re on to song number eleven, “A Lazy Farmer Boy” by Buster Carter and Preston Young. A song from 1930 about a fella who just couldn’t seem to get it together, and who paid the price for his folly.

Is it another song about courtship? Well, you’ll just have to come back and see, won’t you?

As always, I humbly thank you for your attention and thank you in advance for sharing this with folks you think may find it interesting. I didn’t come up with any of this information. I’m just building upon the foundation that others have laid, and putting the pieces together. If you’re interested in learning more about “Willie Moore” or Burnett and Rutherford, the sources I consulted are below.

Sources

Ozark Folksongs Volume IV

Randolph, Vance -

Reprinted by Columbia University of Mississippi Press 1980, pp 311-312

https://archive.org/details/ozarkfolksongs0000rand/page/310/mode/2up

Willie Moore - The Max Hunter Folk Song Collection - Missouri State University (0265)

Cat. #0265 (MFH #691)

As sung by Fred Starr, Fayetteville, Arkansas on October 15, 1958

https://maxhunter.missouristate.edu/songinformation.aspx?ID=0265

Willie Moore - The Max Hunter Folk Song Collection - Missouri State University (1542)

Cat. #1542 (MFH #691)

As sung by David Krussel, Turners Station, Missouri on March 26, 1975

https://maxhunter.missouristate.edu/songinformation.aspx?ID=1542

What's a Daughter To Do? Family Values in the Traditional Ballad "Willie Moore"

For a Song - Back-Issue Article

December 2006

https://www.soundstagenetwork.com/forasong/forasong200612.htm

"Willie Moore" - Sing Out!

https://singout.org/willie-moore/

Dick Burnett (musician) - Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dick_Burnett_(musician)

Richard “Dick” Burnett - Familysearch.org

https://www.familysearch.org/en/tree/person/about/LZP1-WRV

Richard “Dick” Burnett - FindAGrave

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/50807642/richard_daniel-burnett

Leonard Rutherford - Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leonard_Rutherford

Leonard Rutherford - Familysearch.org

https://www.familysearch.org/en/tree/person/about/L16B-58W

Leonard Rutherford - FindAGrave

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/81763202/leonard-rutherford

RICHARD (Dick) BURNETT - Wayne County Musician

Wayne County Museum

Original URL

http://harlanogleky.tripod.com/waynecountymuseum/id23.html (Archived August 17, 2009)

https://web.archive.org/web/20080430092056/http://harlanogleky.tripod.com/waynecountymuseum/id23.html (Retrieved from Internet Archive on May 18, 2025)

Really interesting back story here, I'll have to check out the other entries in this series.

Have to say, the line "In a way no tongue could tell" is brilliant. Not only does it inject a little bit of mystery into the song, but it absolves the writer from having to explain how she died. Imo it's better to leave it up to the imagination. You've got me interested in Burnett & Rutherford, I'm going to have to look these guys up.